Introduction

On January 3, Chinese actor Wang Xing was lured to a fake casting opportunity in Thailand. A vehicle drove Wang to the Thai-Burmese border, sending him instead to KK Park in Myawaddy, the trafficking and cyberscam hotspot. With the help of internet, Wang’s girlfriend’s Weibo post calling for rescue caught the attention of netizens in China, Wang was rescued on January 7, and was escorted back to China 3 days later.[1]

But Wang’s abduction and rescue was far more complex—among other sporadic rescues, it was only the prelude to a greater cleanup. On February 5, Bangkok’s Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) cut off power, gas and internet supply to five Thailand-Myanmar cyberscam compounds.[2] On February 22, Myanmar soldiers had successfully raided KK Park and rescued over 7000 detained individuals.[3]

This article focuses on the international crackdown of KK Park, as well as the development of other scam cities in the Myawaddy District, notably the Yatai City. I argue that although the transnational cooperation in the crackdown was plausible, China, Thailand and Myanmar did not intend to end the “scamdemic” in order to serve their national interests.

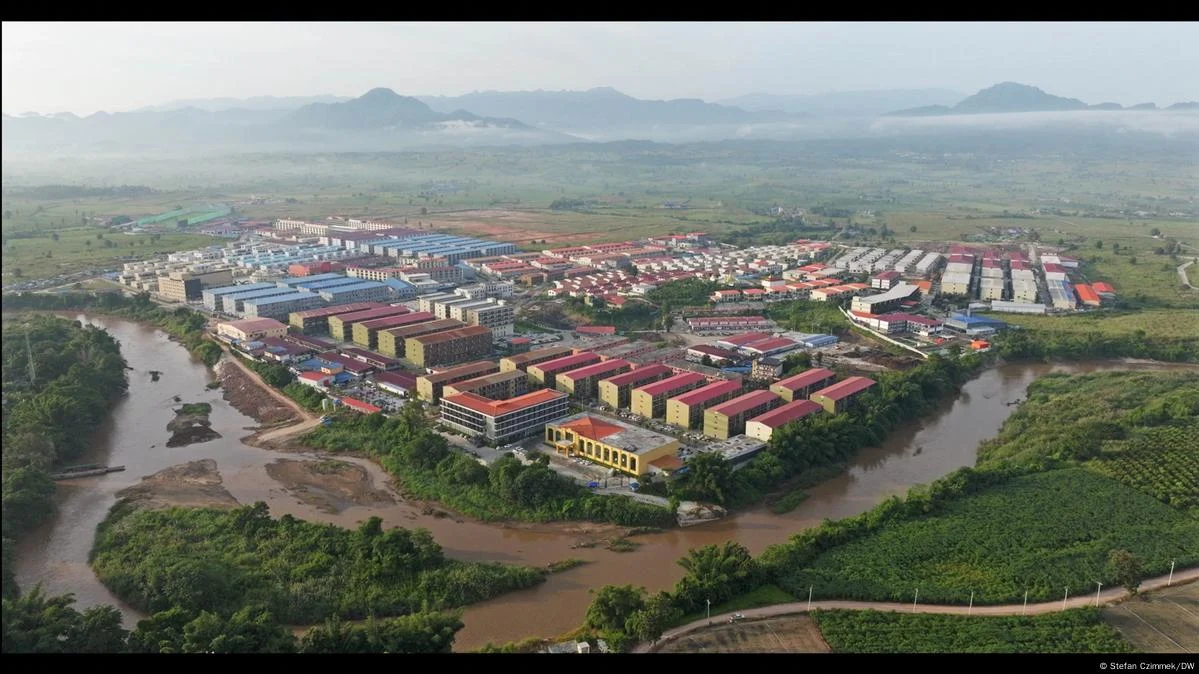

Yatai City in Shwe Kokko township, Myawaddy, Myanmar. (101 East, Al Jazeera)

Myawaddy: Within the “Pig Slaughterhouse”

Firstly, what is the scamming situation like in Myawaddy?

Myawaddy is a district of the Kayin (Karen) State in Myanmar. It borders the Moei river, right across is the Thailand Mae Sot District. There are different townships in Myawaddy, including Shwe Kokko, which is controlled by the Karen warlord Saw Chit Thu.[4] KK Park is situated in another township north of Myawaddy township, controlled by another warlord.[5]

Myawaddy has been known for being the hotspot of scam cities. In 2016, when She Zhijiang, the chairman of the Chinese Yatai International Holdings Group, signed a deal with Saw Chit Thu, promising a $15 billion development project with luxury hotels, casinos and cyberparks in Shwe Kokko. Yatai would provide the capital and construction, while Saw guaranteed the 8,000 fighters in the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) would keep it safe.[6]

However, the reality of Yatai City was a multi-billion dollar call centre conglomerate operating all-encompassing “services” ranging from cryptocurrency, online love scams, online gambling to money laundering.[7]

The scam industry constitutes to “pig slaughtering” cyber slavery: operators closely monitor the abducted victims even when they are asleep, confining their movements to within the buildings, torturing and dehumanizing the victims through handcuffing, whipping and electrification.[8] Synthesized sources point to 220,000 to 300,000 victims across scam complexes in Myawaddy, predominantly male from all across the global south. [9][10]

The fact that these scam cities have been up and running since 2017 and remained unbeaten speaks a lot about the unusualness of Wang’s swift rescue. It was not a sudden realization for the three states that Myawaddy was a cyberscam hotbed. National interests drove the three countries to a crackdown sparked by the heated debate of Wang’s abduction.

The Transnational Interests for Crackdown

Secondly, what led the states to participate in the crackdown?

Wang’s case escalated into a national crisis in China, thanks to his girlfriend’s successful social media campaign. Famous Chinese celebrities, including singer Lay Zhang (張藝興) and actor Qin Lan (秦嵐), have reposted the message. The widespread attention also surfaced a petition of 600 other victims who also disappeared after setting foot in Thailand.[11]

Attention became fear. Flights from China to Thailand plummeted, so did tourism in Thailand, which relies on Chinese tourists.[12] Hong Kong singer Eason Chan also cancelled his concert in Bangkok’s Impact Arena on January 10 “in light of recent safety issues.”[13] Seeing the fear, Beijing sent Assistant Minister of Public Security Liu Zhongyi to visit Thailand and Myawaddy in mid-February and oversaw the crackdown.

To restore confidence and ties with Beijing amidst the 50th anniversary of the bilateral diplomatic relations establishment, Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra directed the power cut on February 5, and discussed the eradication of online gambling and telecom fraud with Xi Jinping during her visit in Beijing the next day.[14]

On the other hand, the Burmese junta Prime Minister Min Aung Hlaing saw the duress from China as an opportunity of a trilateral cooperation, Min coerced breakaway warlord Saw Chit Thu to cooperate with him, leading the junta forces to enter Myawaddy and proceed with the crackdown.[15] However, as I explain in the next section, none of the stakeholders I mentioned intended a complete eradication of the scam industry in Myawaddy.

The National Interests of a Performative Clearance

Lastly, why have the scam centres in Myawaddy not ceased to operate?

China’s Complicity

It is easy to see China as the victim of the cross-border trafficking. 68% of the victims rescued in February were from China.[16] Paradoxically, it was also some Chinese that benefited the most from the transnational scams. Wang Yicheng, a Chinese businessman based in Thailand, was a direct beneficiary from KK Park’s cyberscams, receiving tens of millions of dollars worth of cryptocurrency.[17]

Opinions revealed Beijing is interested in keeping the scam complexes. Macau’s triad leader Wan Kuok Koi is closely affiliated with Wang Yicheng and KK Park in participating in Chinese organized crimes. He publicly supports Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, in which Myawaddy is a target region of China’s BRI investments.[18] The mutual interest between Beijing and the scam centre beneficiaries led anti-scam NGO founder Erin West to believe Beijing had no real intention to stop the “scamdemic”. Not because it could not, but the increasing scams from US citizens also helps weaken China’s superpower rival.[19]

Controversially, She Zhijiang, while detained, has accused China of appointing him as a national spy.[20] He claimed “China wanted a colony,” therefore wanted She to seal the Yatai development project with the Kayin warlord under China’s BRI scheme.[21] While the real intention for China remains ambiguous, the close links between Beijing and the scam masterminds in Myawaddy certainly did not wash away claims for China’s complicity.

Myanmar’s Struggle

The Myanmar coup in 2021 resulted in a civil power struggle in Myawaddy. The revolutions, the Christian-affiliated Karen National Union’s (KNU) Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), has defeated the junta military force. The success did not consolidate the power of KNU, rather making Myawaddy a “no-man’s land.”[22] Regional junta-allied powers emerged for the scramble of influence, such as the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA), and especially the Karen National Army (KNA) led by Saw Chit Thu.[23] KNA was a breakaway ethnic armed organization from the junta force in 2024, and since held power in Myawaddy.[24]

KNA and KNLA had long been accused as being the beneficiaries of colluding with scam centres, Saw was also sanctioned by the UK.[25] Even KNU, the revolutionaries, were allegedly involved with KK Park.[26] The factions have long established deep reciprocities with the scam masterminds, ensuring the scam centers are here to stay.

Thus, the junta’s mission in the crackdown became diversified. On one hand, PM Min Aung Hlaing hoped to unify and recontroll junta-proxy militias in Myawaddy. The backdown of Saw’s KNA proved Min’s agenda to be successful.[27] On the other hand, Min could use the crackdown to “undermine the revolution (KNU),” his biggest foe in Kayin.[28] Most importantly, it presented to the world an impression that the junta is committed to anti-scam.

Scam centres become sites of power struggle under regional warlordism, which benefits them to survive and thrive through double-dipping. Most importantly, according to Justice for Myanmar, the junta also have a record of extracting profits from scam centres to sustain the civil war.[29] The arrival of the junta might even worsen the trafficking situation in Myawaddy.

Thailand’s Ignorance

Who is affected by Thailand’s power cut? Probably not the scam centres, as they “continue to receive fuel supplies” from the rebel KNU’s backup generators. It was indeed the ordinary people in Myawaddy that were the most affected.[30] Gas stations were closed, residents had to buy fuel from the bordering Thai towns instead. Illegal traders also smuggle fuels filled in Mae Sot to be sold in Myawaddy at a higher price.[31]

In June 2023, Thailand also conducted a similar power cut in Myanmar. Thai state claimed the casinos in Shwe Kokko and Lay Kay Kaw to be its targets, yet the casinos’ operation was largely unaffected.[32] If Bangkok was aware of the ineffectiveness of cutting power exports, why do they still put this on show?

The reason is, they do not hope the scam cities in Myanmar will stop. Firstly, by promulgating the supply cut soon enough, the scam compounds prepared diesel generators earlier and could stay in Myanmar. As a result, the Thai government prevents a massive influx of scammers and a crime rate surge. Second and most importantly, Thai merchants already profited from the construction of scam compounds, as they sell everything from concrete, construction materials, to the computer terminals and food to the scam centres.[33]

With politics aside, Thailand retained minimum effort in peacekeeping due to the bribery of high-ranking police officers.[34] Critics condemned Bangkok’s negligence in the regional affairs may lead to a potential civil outbreak in Myawaddy.[35] However, such ignorance advanced Thailand’s national interest in maintaining the political weakness of Myanmar.

Conclusion

The recent Sino-Burmese-Thai crackdown and the situation in other Myawaddy scam centers reflect that the three states prioritize national interests over complete eradication of cyber slavery. Nevertheless, the carefully orchestrated performance did successfully create an illusion of a genuine crackdown.

Following the history, it is not hard to forecast that the crackdown of KK Park will not last long. The centre will reconvene, the recruitment will continue, and a new batch of victims will be trafficked to the complexes. Moreover, the incomplete crackdown failed to address other complexes running in Myawaddy. If there is no total intervention to Myawaddy’s “scamdemic,” there is no end to this problem.

Alvin is a second-year majoring in International Relations and Contemporary Asian Studies. Originally from Hong Kong, Alvin is inspired by geopolitics about East and Southeast Asia, specifically grassroots mobilization and state oppression, economic and urban development, and cultural diversity. On top of Synergy, Alvin is a student affiliate at the Centre for the Study of Global Japan (CSGJ), and the president of UofT’s Cantonese Debate Club. Here in Synergy, Alvin is determined to unravel issues like self-determination, diplomatic policy, and global investments revolving around Southeast Asia.

Bibliography

Abuza, Zachary. “OPINION: China pushes Thailand to act on cross-border scam centers.”

Radio Free Asia, 19 February, 2025. https://www.rfa.org/english/opinions/2025/02/19/opinion-china-thailand-myanmar-scam-center-zachary-abuza/.

“BGF detains more than 7,000 citizens of 29 nations following crackdowns on scams.” The

Nation, February 26, 2025. https://www.nationthailand.com/news/asean/40046727.

Campbell, Charlie. “Is China Really Powerless to Stop the ‘Scamdemic’? The Truth Is More

Complex.” Time, 21 January, 2025. https://time.com/7208652/china-pig-butchering-scamdemic-crack-down/.

Chen, Meredith. “China, Thailand pledge joint action on Myanmar cyber scam centres,

human trafficking.” South China Morning Post, 30 Jan, 2025. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3296831/china-thailand-pledge-joint-action-myanmar-cyber-scam-centres-human-trafficking.

Ewe, Koh. “How a viral post saved a Chinese actor from Myanmar’s scam centres.” BBC

News, 9 January 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cd606l1407no.

“KNU: Junta May Use Scam Centre Crackdown to Undermine the Revolution.” Karen News,

accessed March 13, 2025. https://karennews.org/2025/02/knu-junta-may-use-scam-centre-crackdown-to-undermine-the-revolution/.

Mallikka, Miabell. “Thailand cuts power to Myanmar casinos, but they keep operating,”

Scandasia (Bangkok), 7 June, 2023. https://scandasia.com/thailand-cuts-power-to-myanmar-casinos-but-they-keep-operating/.

”Myanmar soldiers raid K.K. Park, rescuing victims of call-centre gangs.” The Nation, 22

February 2025. https://www.nationthailand.com/news/asean/40046586.

Naing, Aung. “Karen BGF to rename itself ‘Karen National Army’.” Myanmar Now, March

6, 2024. https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/karen-bgf-to-rename-itself-karen-national-army/.

Phaicharoen, Nontarat. “Thailand cuts power to Myanmar’s scam centers in anti-crime push.”

Radio Free Asia Burmese, 4 February 2025.

Sanders IV, Lewis et al.. “How Chinese mafia are running a scam factory in Myanmar.”

Deutsche Welle (DW), 30 January, 2024. https://www.dw.com/en/how-chinese-mafia-are-running-a-scam-factory-in-myanmar/a-68113480.

She Zhijiang: Discarded Chinese spy or criminal mastermind? 101 East: Al Jazeera. 26 Sep

2024. Video, 25:15,

“Thailand’s power and fuel cuts hurting ordinary Myanmar residents.” Radio Free Asia, 11

March, 2025. https://www.rfa.org/english/myanmar/2025/03/11/myanmar-thailand-fuel-price-spike/.

Wongcha-um, Panu, and Devjyot Ghoshal, “Thailand’s scam centre crackdown not enough,

top lawmaker warns.” Reuters, February 27, 2025.

Wong, Wynna. “Hong Kong’s Eason Chan axes Thai show over ‘safety issues’ for Chinese

citizens.” South China Morning Post, 10 Jan 2025. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3294301/hong-kongs-eason-chan-axes-thai-show-over-safety-issues-chinese-citizens.

“Xi Jinping Meets with Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra.” Ministry of Foreign

Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, 6 February, 2025. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202502/t20250207_11550783.html.

- Koh Ewe, “How a viral post saved a Chinese actor from Myanmar’s scam centres,” BBC News, 9 January 2025. ↑

- Nontarat Phaicharoen, “Thailand cuts power to Myanmar’s scam centers in anti-crime push,” Radio Free Asia Burmese, 4 February 2025. ↑

- ”Myanmar soldiers raid K.K. Park, rescuing victims of call-centre gangs,” The Nation, 22 February 2025. ↑

- She Zhijiang: Discarded Chinese spy or criminal mastermind? 101 East: Al Jazeera, 26 Sep 2024. Video, 25:15, https://www.aljazeera.com/program/101-east/2024/9/26/she-zhijiang-discarded-chinese-spy-or-criminal-mastermind. ↑

- She Zhijiang. ↑

- She Zhijiang. ↑

- She Zhijiang. ↑

- She Zhijiang. ↑

- Panu Wongcha-um and Devjyot Ghoshal, “Thailand’s scam centre crackdown not enough, top lawmaker warns,” Reuters, February 27, 2025. ↑

- Charlie Campbell, “Is China Really Powerless to Stop the ‘Scamdemic’? The Truth Is More Complex,” Time, 21 January, 2025. ↑

- Koh, “How a viral post saved a Chinese actor from Myanmar’s scam centres.” ↑

- Koh, “How a viral post saved a Chinese actor from Myanmar’s scam centres.” ↑

- Wynna Wong, “Hong Kong’s Eason Chan axes Thai show over ‘safety issues’ for Chinese citizens,” South China Morning Post, 10 Jan 2025. ↑

- “Xi Jinping Meets with Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, 6 February, 2025. ↑

- “China and Thailand target Myanmar’s sin city.” ↑

- “BGF detains more than 7,000 citizens of 29 nations following crackdowns on scams,” The Nation, February 26, 2025. ↑

- Lewis Sanders IV et al., “How Chinese mafia are running a scam factory in Myanmar,” Deutsche Welle (DW), 30 January, 2024. ↑

- Sanders IV et al., “How Chinese mafia are running a scam factory in Myanmar.” ↑

- Campbell, “Is China Really Powerless to Stop the ‘Scamdemic’?” ↑

- She Zhijiang. ↑

- She Zhijiang. ↑

- “China and Thailand target Myanmar’s sin city.” ↑

- “KNU: Junta May Use Scam Centre Crackdown to Undermine the Revolution,” Karen News, accessed March 13, 2025. ↑

- Aung Naing, “Karen BGF to rename itself ‘Karen National Army’,” Myanmar Now, March 6, 2024. ↑

- She Zhijiang. ↑

- Naing, “Karen BGF to rename itself ‘Karen National Army’.” ↑

- “China and Thailand target Myanmar’s sin city.” ↑

- Naing, “Karen BGF to rename itself ‘Karen National Army’.” ↑

- “KNU.” ↑

- Phaicharoen, “Thailand cuts power to Myanmar’s scam centers in anti-crime push.” ↑

- “Thailand’s power and fuel cuts hurting ordinary Myanmar residents,” Radio Free Asia, 11 March, 2025. ↑

- Miabell Mallikka, “Thailand cuts power to Myanmar casinos, but they keep operating,” Scandasia, 7 June, 2023. ↑

- Zachary Abuza, “OPINION: China pushes Thailand to act on cross-border scam centers,” Radio Free Asia, 19 February, 2025. ↑

- Meredith Chen, “China, Thailand pledge joint action on Myanmar cyber scam centres, human trafficking,” South China Morning Post, 30 Jan, 2025. ↑

- “China and Thailand target Myanmar’s sin city – junta set to benefit.” ↑