Content warning: This review contains mentions of graphic and potentially traumatic subjects, including sexual and gender-based violence, wartime violence in internment camps, and suicide. Reader discretion is advised.

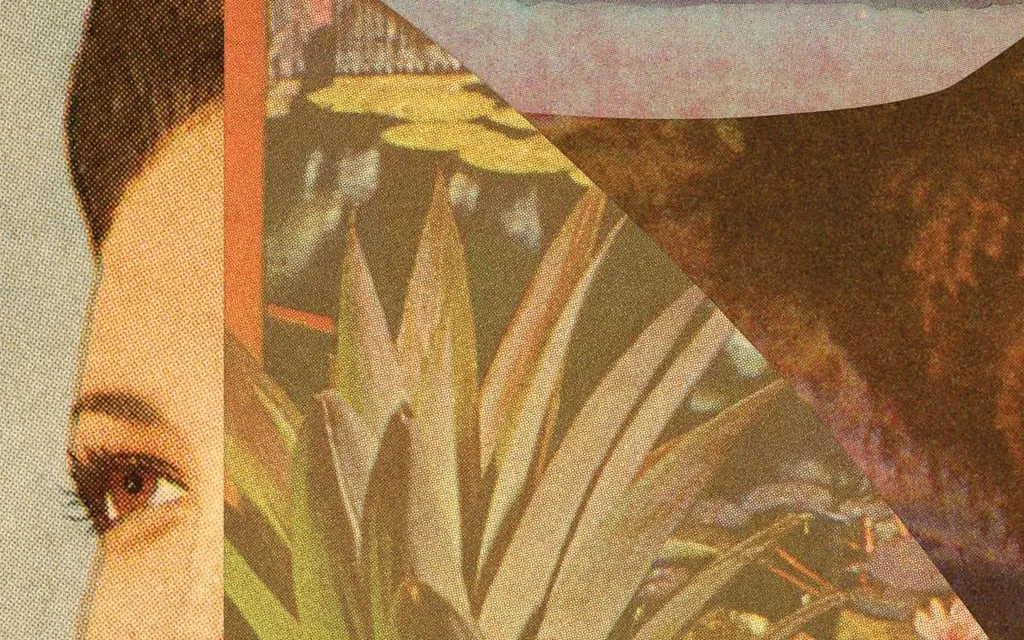

At first glance an intergenerational story of suffering and tragedy, Eka Kurniawan’s Beauty is a Wound constructs the image of a nascent nation by arranging interrelated, winding branches of the central character’s family. Readers wandering into the novel’s enrapturing world are engulfed by the fictional coastal town of Halimunda, along with its surrounding forest and fishing villages that seem to exude a subtle touch of supernatural mystery. Dewi Ayu, a mixed-race granddaughter of Dutch plantation owners, is thrust into prostitution upon the Japanese invasion and occupation of the Indies. Having lived through immense wartime hardship, her three daughters become all but subject to similar episodes of violence, abuse, and manipulation despite the conclusion of foreign occupation. Taking the novel at face value leads the unwary reader to conclude that the exceptional beauty of Dewi Ayu and her daughters, unfortunately, begets cruel subjugation at every turn—but the details between the lines echo the struggles of a “beautiful” native Indonesia against torrential bouts of colonial violence.

Spanning the early 20th century to just before the new millennium, the dimensions of Indonesian history covered in Beauty Is a Wound are defined by a violent, repressive timeline. Beginning with glimpses into Dutch colonial rule, the novel goes on to detail the lives of prominent Halimunda characters during the onset of Japanese occupation during WWII, Indonesia’s National Revolution and subsequent independence, and the anti-Communist purge of 1965; at last concluding with the collapse of Suharto’s New Order administration. This expansive timeline cleverly emphasizes a core theme of interconnectedness: the book’s beginning situates the reader in a colonial moment in time a few generations before Dewi Ayu is even born. We are introduced to Ma Gedik, a native teenage boy irrevocably heartbroken when his sweetheart, Ma Iyang, is carted away to become a concubine for a Dutch plantation owner. Upon escaping from the plantation sixteen years later, Ma Iyang reunites with her lover as promised the day she entered into concubinage, then jumps off of a cliff into the valley below to evade certain punishment by the Dutchmen. In recounting her upbringing some years later, Dewi Ayu reveals that she is the daughter of Aneu Stammler, born to plantation owner Ted Stammler and his native concubine, Ma Iyang.

Beauty Is a Wound personifies the story of Indonesia’s nationhood through Dewi Ayu and her family. Dewi Ayu’s half-native, half-Dutch ancestry reflects Indonesia’s character born from a combination of native and colonial cultural elements. The sexual violence and forced prostitution she later suffers during Japanese occupation is evocative of the wounds suffered by the nation as a whole at the hands of the Japanese forces. Among her daughters, some are born to Japanese

soldiers, and others are married to former Japanese combatants. Here, Kurniawan’s narrative choices are ostensibly deliberate: these family relations suggest the inseparable Japanese influence on Indonesia’s identity. The book’s tremendous plot is embellished by an arsenal of strong narrative elements—primarily, the use of magic realism. Combining a story of colonial violence and suffering told in vivid detail with supernatural, fantastical tellings of certain pivotal events pokes at the reader’s awareness of another overarching theme of discursive truth. For instance, Ma Iyang’s fateful leap into the valley does not entail a gruesome death. Proclaiming that “if you believe you can fly, you can fly,” Ma Iyang’s disappearance into the sky came to be believed by locals when they were unable to find her body despite scouring every corner of the valley.[1] Equally demonstrative of magic realism is the very first line of the book: “One afternoon on a weekend in March, Dewi Ayu rose from her grave after being dead for twenty-one years.”[2] Additionally, Kurniawan’s wry sense of humour goes a long way in reducing the distance between the reader and the novel’s characters and events. A playful, though dark style of prose paints Dewi Ayu as a character who, despite suffering tremendous violence, sexual abuse, and wartime poverty, always has a matter-of-fact quip that humanizes this suffering for the reader. After offering to have sex with a Japanese soldier to obtain medical attention for her friend’s sickly mother in an internment camp, Dewi Ayu comforts her distraught friend, saying “It was nothing. Just think of it like I took a shit through the front hole.”[3]

Historically speaking, the contents of Beauty is a Wound are relevant to academic explorations of gender and nation-building in Indonesia. Ann Laura Stoler, a Professor of Anthropology previously at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Michigan, has written on the intersection of concubinage and colonial politics in Indonesia. In her essay Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule, Stoler posits that concubinage was strategically made an attractive option to European men working in the Indies by the Dutch East Indies Company. Behind this strategy was the goal of dissuading European female emigration due to the high costs of transport, fears that Dutch women would convince their husbands to “repatriate [back to the Netherlands] to display their newfound wealth,” and that the poor health of European children living in the Indies would force families to repatriate and ultimately deplete the colony of permanent settlers.[4] Though concubinage is not necessarily a recurring topic throughout the novel, it is positioned at the foundation of a critical premise: the alleged curse cast by Ma Gedik on Ma Iyang’s descendants, to which Dewi Ayu attributes her family’s scores and scores of suffering. The fight for Indonesian self-determination serves mostly as the background to the tragedy that follows Dewi Ayu’s daughters, but its brief mention nonetheless poignantly situates the characters’ struggles against the backdrop of the culmination of native efforts for independence. Halimunda residents’ annual celebrations of independence came to include street fairs, reciprocal gifting of food baskets, saluting the flag of Indonesia, and the singing of the national anthem Indonesia Raya, which brings to mind the Sumpah Pemuda (Youth Oath) made by participants at the 1928 All Indonesia Youth Congress to mark the beginning of a commitment to national unity and freedom.[5] Indonesia’s independence coincides with a happy, peaceful stage of life for Dewi Ayu’s daughters; paralleling the momentary calm of a nation previously embroiled in a battle against colonial violence.

While undoubtedly a heavy read with many grim and macabre themes, the ultimate product of Kurniawan’s craft is a detailed snapshot of Indonesian history that captures the vivid brutality of colonial rule and its implications for the nation’s present identity. There is much left uncovered in this review, and I strongly recommend Beauty Is A Wound to those interested in learning more about colonial history in Asia.

Silin Wei is a student pursuing a double major in Peace, Conflict, and Justice Studies & Contemporary Asian Studies along with a minor in Political Science. Her research interests include climate resilience, equitable education reform, and gender in politics, building on her prior work in researching food justice and related patterns of inequity in the Greater Toronto Area. As a Contributor at Synergy, she hopes to explore the approaches taken by Asian states to shifting global power balances and transnational challenges through an interdisciplinary lens.

Bibliography

All Indonesia Youth Congress. 1928 [2009]. “Sumpah Pemuda [The Youth Oath],” In Tineka Hellwig and Eric Taliacozzo (eds), The Indonesia Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 269-70.

Ann Laura Stoler, and Micaela di Leonardo. 2023. “Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Gender, Race, and Morality in Colonial Asia.” In Gender at the Crossroads of Knowledge, 1st ed., 51-. University of California Press.

Kurniawan, Eka. 2016. Beauty Is a Wound. Translated by Annie Tucker. London Pushkin.

Footnotes

-

Eka Kurniawan, Beauty Is a Wound, (London Pushkin, 2016), 39 ↑

-

Kurniawan, Beauty Is a Wound, 1 ↑

-

Kurniawan, Beauty Is a Wound, 71 ↑

-

Ann Laura Stoler, “Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Gender, Race, and Morality in Colonial Asia,” In Gender at the Crossroads of Knowledge ed. Micaela di Leonardo (1st ed., 51-. University of California Press, 2023), 16. ↑

-

All Indonesia Youth Congress. “Sumpah Pemuda [The Youth Oath],” In The Indonesia Reader: History, Culture, Politics, ed. Tineka Hellwig and Eric Taliacozzo (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1928 [2009]), 269 ↑