By analyzing how Southeast Asian countries navigate and thrive under the competing influences of China and the U.S, I aim to uncover how smaller nations effectively manage to maneuver and adapt amidst the power struggles of global giants. In this paper, I show that Southeast Asian countries maintain diverse regional and economic ties with China, which significantly influence the variations in their foreign policies toward Beijing. Additionally, I argue that despite the ongoing great power rivalry in the region, smaller states are not passive recipients of great power policies. Instead, they actively craft strategies aligned with their national interests to safeguard diplomatic autonomy and achieve economic prosperity. I will begin by outlining the respective interests of the U.S. and China in Southeast Asia and examining how their competition has increasingly focused on this region. Although many U.S. politicians criticize the lack of depth in America’s policy toward Southeast Asia, successive administrations, from Obama to Trump, have not overlooked the region’s strategic importance. A peaceful and stable Southeast Asia not only benefits U.S. free trade and investment but also positions Southeast Asian countries as allies that can help counterbalance China’s regional development and power projection. China’s policy toward Southeast Asia is not one-sided but instead rather complex. While a stable and peaceful Southeast Asia aligns with China’s interests, Beijing remains resolute on sensitive issues such as the South China Sea and Taiwan. I will illustrate how China’s power projection in the region creates symmetrical constraints and challenges that are felt by all Southeast Asian countries. Finally, using the examples of Singapore, Vietnam, and Cambodia, I demonstrate how Southeast Asian countries leverage great power rivalry and China’s regional interests to their advantage. They employ strategies such as hedging, soft balancing, and bandwagoning to navigate the relationship, reaping economic benefits while maintaining strategic vigilance.

United States-China Rivalry in Southeast Asia

When analyzing China’s political intentions and foreign policy actions in Southeast Asia, it is essential to consider the role of the United States. U.S. policies significantly shape China’s interpretations of its foreign interests and reflect the increasingly competitive strategic dynamic between the two powers in the region.The U.S. views the region as a crucial maritime zone with vast sea spaces, emphasizing its responsibility to maintain open sea lanes for international trade. More importantly, it ensures the U.S. retains unrestricted access to the oil-rich Persian Gulf and its Northeast Asian allies, Japan and South Korea.[1] With China’s increasing actions and impacts in the Asia pacific and heightened competition between the two major powers, Southeast Asia gains additional strategic importance as a key partner for containing China’s increasing influence in the region. Thus, for the U.S., the region has growing economic and strategic importance. Although strategic competition between the U.S. and China in the region had already been ongoing for some time, the maneuvering between the two great powers intensified following the Obama Administration’s introduction of the “Pivot to Asia” policy.[2] Over eight years, Obama visited nine out of ten ASEAN countries, signing numerous bilateral agreements including military assistance and defense pacts with Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore.[3] Between 2010 and 2016, the administration delivered $4 billion in development assistance and strengthened U.S. ties with Southeast Asia through the 2016-2020 ASEAN-U.S. Plan of Action.[4] This plan was initiated with the goal to comprehensively increase cultural and commercial exchanges between the two regions. China was clearly a driving factor behind the U.S. intensification of policies toward Southeast Asia. Key figures, such as Kurt Campbell, conceptualized the U.S. “pivot” or “rebalance” to Asia as a strategy to embed the United States’ China policy within a broader Asia framework.[5] Although the Trump administration’s engagement with Southeast Asia was not as comprehensive as that of the Obama administration, the FOIP (Free and Open Indo-Pacific) initiative directly aimed to restrain China’s influence in the region. At its core, FOIP is a maritime security and economic strategy aimed at ensuring that the Indo-Pacific remains free from coercion and open for fair trade, navigation, and investment. It opposes unilateral actions that disrupt regional stability, such as China’s military expansion in the South China Sea and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, including the development of logistics bases in the Indian Ocean.[6] The Indo-pacific strategy under both the Obama and Trump administrations have sought to counterbalance Chinese activities in Asia.

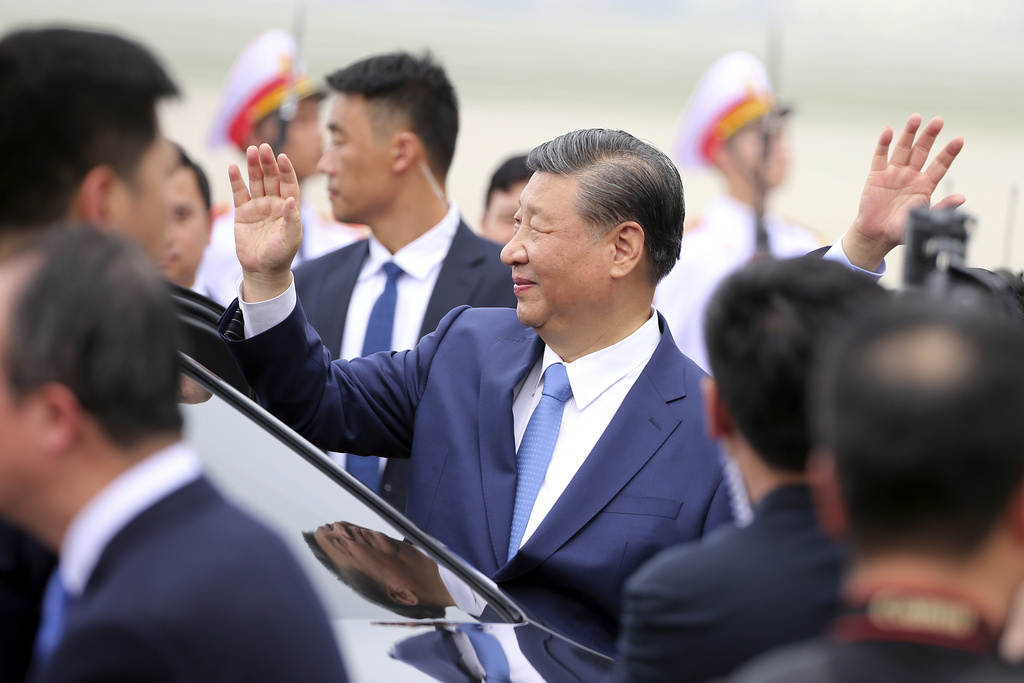

On the other hand, one of China’s strategic priorities is to secure its surrounding region and prevent encirclement by a rival power. Beijing attempts to ensure that Southeast Asia does not align with a power hostile to China, such as the U.S. or Japan.[7] Despite the criticism that both FOIP and Obama’s high-profile engagement in Southeast Asia focused more on rhetoric than on action, they were seen by China as hostile moves, prompting China to intensify its influence in the region. China’s engagement in the region is primarily economic rather than militaristic. A prominent example is Xi’s flagship initiative, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which involves an estimated investment of over $1 trillion to develop infrastructure, foster trade links, and strengthen economic ties between China and numerous countries, including many in Southeast Asia.[8] China often describes this initiative as a win-win project, or specifically speaking, the BRI benefits China. For example, the Pan-Asia Railway, if completed, would integrate China and Southeast Asia into a unified super free trade zone.[9] China relies heavily on imported resources like oil, copper, and cobalt for its economy and industries, particularly electric vehicles, with key supplies coming from the Persian Gulf and Africa.[10] These imports depend on maritime routes such as the Strait of Malacca, a critical but vulnerable chokepoint influenced by the U.S. and plagued by risks like shallow waters and sediment buildup.[11] To address these challenges, China and Thailand have explored the possibility of constructing a canal across the Kra Isthmus, which lies between Ranong Province and Chumphon Province in Thailand. This canal would shorten trade routes by approximately 1,000 kilometers, providing a more efficient alternative to the Strait of Malacca.[12] This dynamic also highlights the contrasting sets of tools the two powers employ to achieve their national objectives. The most striking difference is China’s economic strengths compared to America’s military dominance, a contrast that is particularly evident in Southeast Asia.[13] From an economic perspective, both China and the United States have a shared interest in maintaining peace and stability in Southeast Asia to reap the benefits of free trade, investment opportunities, and access to critical resources. However, one could argue that the security dilemma introduces significant uncertainty, as each side may adopt aggressive policies to act out of fear that the other will seize a first-mover advantage. This dynamic risks undermining each power’s initial objective of opposing hegemony in the region and could ultimately resemble a hegemonic role and force Southeast Asian countries to take sides.

The Dragon looks South: China’s Interests in Southeast Asia

China sees Southeast Asia as a neighboring community sharing geographical proximity and historical linkages, thus, a community of the same fate makes the region where China can expand its access and influence. China’s deepening relationships with Southeast Asian countries has grown out of the PRC’s increased emphasis on “peripheral diplomacy.”[14] A key objective of Chinese foreign policy is to build political alliances and promote a peaceful, stable Southeast Asia, which aligns with China’s interests in advancing its economy, expanding trade, and benefiting from the region’s prosperity.[15] China’s foreign policies to cultivate a good relationship with Indonesia and Vietnam are great examples of this. During the Suharto regime, Indonesia severed diplomatic ties with Beijing, driven by anti-Chinese policies including the persecution of ethnic Chinese and a broader climate of racism. Diplomatic relations between the two countries eventually resumed in 1985.[16] Over time, China and Indonesia have worked to strengthen their relationship despite challenges such as the South China Sea dispute. For Indonesia, deepening ties with China has offered a sense of participation in a rapidly changing global landscape.[17] China sees building a friendly and cooperative relationship with Indonesia as vital for several strategic and geopolitical reasons. As the largest nation in Southeast Asia and the guardian of the Strait of Malacca, Indonesia holds significant strategic value. Control or influence over this region would help China secure critical maritime trade routes.[18] Moreover, Indonesia’s potential to exert regional pressure—whether through a hypothetical military partnership or cooperative relations—highlights its importance to China’s broader strategy in the region.[19] A similar narrative goes for Vietnam. We see that China’s foreign policy of peripheral diplomacy reflects its effort to actively foster cooperation and build positive relationships. From China’s perspective, this approach involves moving past historical conflicts and differences while leveraging soft power to expand its influence.

However, Beijing’s policies towards the region are somewhat complicated, often marked by conflicting objectives. Specifically, China’s national security concerns sometimes clash with its economic interests in the region, creating a dilemma in determining which policies to prioritize and implement.[20] This is because Beijing’s engagement with Southeast Asia is also deeply intertwined with its national security priorities, particularly the protection of territorial integrity and the preservation of Chinese sovereignty. The South China Sea dispute is an especially prescient example of these phenomena, as China’s claim to the territory is a common security concern for Southeast Asian countries. Beijing’s 1992 claim over the entire South China Sea was particularly unsettling for Southeast Asian countries, especially those reliant on free navigation through open sea routes for trade. Many argue that China has always desired to pre-empt Southeast Asian countries through a divide and weaken policy. For instance, the country has long employed a divide-and-weaken strategy regarding the South China Sea, meaning it avoids multilateral discussions and leverages its dominance by negotiating with individual claimants one at a time.

Structural Constraints Resulting from China’s Influence and Actions in the Region

Southeast Asia’s history of foreign intervention and internal fragmentation has fostered a strong aversion to the concentration of power, whether by a regional actor or an external one. The post-independence rivalry between Indonesia and Malaysia, particularly over leadership within the region, highlighted the risks of dominance by any one state, serving as a reminder to the region about the importance of maintaining balance and avoiding hegemony.[21] Given such a historical experience, Southeast Asia’s major concern is the potential for China to dominate the region to the exclusion of other major players. This fear centers on China’s growing influence and its ability to exercise regional hegemony, which could marginalize other states and disrupt the balance of power in Southeast Asia. This concern is compounded by uncertainty about China’s strategic intentions and the need to manage this vulnerability, especially in relation to the role of the United States in regional security.[22] Furthermore, tensions are amplified when Beijing and Washington adopt more aggressive policies toward one another, escalating global competition. Such dynamics risk heightening regional tensions, particularly around the issue of Taiwan, and could ultimately force Southeast Asian countries to take sides.

Although Beijing has employed more incentives than coercion so far, the uncertainty surrounding China’s long-term intentions and growing power appears to cause greater concern than benefits for Southeast Asian countries. Nearly all Southeast Asian countries feel a shared sense of pressure as China’s influence and use of soft power continue to grow across the region, encompassing areas such as economic ties, trade, culture, and human capital exchange. China’s significant financial investments to strengthen ties with ASEAN countries are often perceived as assertive and demanding, reflecting the asymmetry in their relationship. In 1996, China became a full and official “dialogue partner” of ASEAN, initiating a process of annual China-ASEAN summits.[23] Over the years, China has made consistent efforts to deepen its relationship with ASEAN countries through frequent high-level bilateral interactions and institutionalized mechanisms. They include ten joint ministerial mechanisms and more than twenty senior official mechanisms. In 2008, to further demonstrate its commitment, China established a dedicated diplomatic mission to ASEAN and appointed its first ambassador to the organization.[24] These examples clearly illustrate that Beijing is the impetus behind efforts to advance its relationship with ASEAN, although this has at times resulted in a sense of being overwhelmed and “dialogue fatigue” among member states.[25]

Many scholars argue that Southeast Asia has become a key factor of China’s plan for economic prosperity and the rejuvenation of its great civilization. As part of its plan, Beijing sees Southeast Asia as inherently subordinate and compliant with its interests and demands. They contend that China seeks to revive the pre-colonial “tribute system,” where resources traditionally flowed from the so-called “barbaric” South to the “civilized” center in the North.[26] They further highlight that Southeast Asia’s vulnerability is as appealing as its increasing wealth and abundance of resources to Beijing. Traditionally referred to in Chinese perception and parlance as the “South Seas” and the “Golden Lands,” Southeast Asia stands in sharp contrast to the more fortified Northeast Asia, being both vulnerable and penetrable.[27] China’s Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi’s 2010 remark, “China is a big country, and other countries are small countries,” reflects a realist perspective rooted in China’s dominant history that highlights power asymmetry in the relationship.[28] Compared to the United States’ historical strategy of regional influence, China appears to have little interest in pursuing military buildups in Southeast Asia, as a peaceful and prosperous region aligns with its economic interests—though the South China Sea may be an exception. However, this does not imply that soft coercion and economic punishments will not necessarily occur.[29] In fact, Beijing is likely to engage closely with Southeast Asian national leaders on policy matters and expect them to align with its preferences when required.[30] In other words, these scholars tend to view the China-Southeast Asia relationship as highly asymmetrical: one side actively takes the initiative to set demands, while the other passively complies with them, leaving little room for maneuvering.

Southeast Asian Countries’ Agency amid Great Power Rivalry

While Southeast Asian countries face a symmetrical pressure from China’s growing power projection and uncertainty surrounding future power dynamics between the U.S. and China, the conventional view that Southeast Asian nations are merely passive recipients or tools of great power competition is not entirely accurate. In fact, Southeast Asian countries assert their agency by adopting flexible and adaptive strategies that prioritize their national interests, enabling them to maintain diplomatic autonomy and achieve economic prosperity. In other words, rather than passively reacting to China’s foreign policies, Southeast Asian countries actively craft strategies driven by their own interests and priorities, leveraging great power competition in the region to their advantage.

Great power rivalry is not entirely bad for Southeast Asia, as it provides small and middle powers the opportunities to maneuver and benefit from the competition, such as accessing economic resources and securing military protection that would not otherwise be available. In terms of economic development, Southeast Asian countries benefit from China’s rising economy by fostering trade and collaborating across various dimensions, including culture, human capital exchange, and advancements in technology and artificial intelligence. ASEAN countries enhance their military security by leveraging relationships with great powers and investing in their own defense capacities. Many nations strengthen ties with the United States through joint military exercises and forging closer defence ties with the U.S. to counter the growth of Chinese military power.[31] To reduce reliance on a single power, they also diversify security partnerships with India, Russia, Australia, the United Kingdom, and China.[32] Rather than passively being recipients of great power foreign policies, Southeast Asian countries assert agency by building internal capacity while maintaining soft and spontaneous relationships with regional powers.

Strategies and Approaches

The majority of Southeast Asian countries adopt a non-aligned strategy, perceiving antagonistic alliances as overly confrontational and prone to miscalculations, which could lead to domination by external powers.[33] To accomplish this, their primary strategy is a highly flexible and pragmatic policy of engagement and strategic engagement by leveraging China’s regional interests by accommodating its economic demands while simultaneously maintaining a cooperative yet cautious military relationship with the United States. This approach seeks to encourage China to choose international cooperation over unilateral actions or aggression. The underlying idea is that economic integration and interdependence with other major powers would demonstrate to China that cooperation yields far greater benefits than attempting to expand its sphere of influence independently.[34] While China’s engagement with ASEAN is often viewed as unilateral, it is also in ASEAN countries’ interest to use regional and international organizations to socialize China into accepting and adhering to established norms and principles.[35] By integrating China into these institutions, Southeast Asian states aim to create obligations and expectations that encourage China to act within the framework of international rules and standards. At the same time, Southeast Asian states strive to foster strategic interdependence between China and other major powers, particularly the United States, to cultivate strong economic and strategic ties, thus making conflicts more costly and preventing rivalry from escalating.[36] We see that the US-China competition is not purely bilateral, as other actors play a significant role. In fact, the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) help mitigate and influence the dynamics of this superpower rivalry.[37] Far from being Asia’s “soft underbelly” lacking agency and self-determination, Southeast Asian countries are actively leveraging China’s interests and U.S.-China competition in the region to their advantage. Southeast Asian countries understand well that economically, China relies on Southeast Asia for resources, markets, and regional stability to sustain its growth.[38] Additionally, ASEAN’s collective stance on the South China Sea dispute and its members’ pro-US defense ties act as checks on China’s influence, restraining China’s military build up and potential aggressive actions.[39]

The strategy adopted by any particular Southeast Asian country depends on that country’s geographical proximity to China, its position on the South China Sea, and the security and economic opportunities or challenges posed by China’s rise in the region. Countries like Singapore, which consider military power and geographical proximity crucial for policy decisions toward China and view open sea navigation as essential for long-term sustainable growth, are more likely to adopt a balancing strategy.[40] When a state employs a balancing strategy, it positions itself against a perceived threat to enhance security and deter conflict. This can be done through hard balancing, such as forming alliances and boosting military power, or soft balancing, which involves economic cooperation, military collaboration without formal alliances, and diplomatic efforts to frustrate the threatening power’s goals. The main aim of this tactic is to strengthen the state’s own security while increasing the costs for the threatening power, thereby deterring aggression.[41] In the case of Singapore and the Philippines, this involves supporting the United States in maintaining its naval dominance to counterbalance China’s military presence in the region.

Countries that perceive China’s rise to pose minimal regional security threats and hold optimistic economic expectations about their relationship with Beijing are more inclined to view China as a friendly neighbor and adopt a “bandwagoning” strategy.[42] Different from balancing, countries that bandwagon choose to side with the “stronger” power based on its calculation of self interests. This alignment may include forming military alliances or deepening economic relationships, driven by the goal of benefiting from China’s rise or reducing potential threats. Bandwagoning emphasizes cooperation with China over maintaining ties with other major powers, seeing it as a way to gain advantages rather than just ensuring survival.[43]

Countries that have strong economic ties with Beijing but are concerned about China’s long-term ambitions, particularly potential maritime threats, are likely to adopt a “hedging” strategy.[44] The strategy of hedging involves preparing for a potential threat by engaging with the perceived risk in various areas such as military, economic, and political spheres, while also employing soft or indirect balancing as a form of deterrence.[45] Unlike balancing, which responds to an existing threat, and bandwagoning, which aligns with a stronger power to gain benefits, hedging is focused on mitigating the possibility of a future threat without directly confronting it. When a rising external power, whether it be China or the U.S, creates both threats and opportunities, regional stability is most effectively achieved when countries in the region adopt a combination of those strategies. In the case studies of several Southeast Asian countries, particularly Singapore, fostering a positive international image and maintaining strong relationships with neighboring states enables them to remain united and discourages potential aggressors from pursuing hostile actions in the region. In other words, ASEAN countries prioritize their self-interest by adjusting their foreign policies toward China based on their national interests within the economic and security structure of the region.

Singapore’s Strategy amid China’s Power Projection in the Region

In Singapore’s case, we see that the country adopts a hedging strategy towards China, which is highly flexible and changes based on the fluctuating threat level posed by the powerful state. Its hedging strategy is threefold: fostering economic interdependence, pursuing security alliances, and maintaining a regional balance of power.[46] Unlike Vietnam, which suffers a trade deficit with China, Singapore’s strong service sector allows it to compete with China’s industries. In 2023, Singapore achieved a trade surplus, with exports to China exceeding imports from China.[47] Overall, Singapore benefits greatly from China’s economic rise. For a long time, the People’s Action Party (PAP)’s economic imperatives behind Singapore’s China policy are driven by the desire to capitalize on economic opportunities in China, particularly through trade, investment, and economic cooperation.[48] The complementary nature of their economies encouraged Singapore to deepen ties with China, and initiatives like the Suzhou Industrial Park project to transfer skills and investment.[49] Since 2013, China has been Singapore’s largest trading partner, and the two countries have continued to strengthen economic cooperation, regularly upgrading trade agreements. In 2020, their trade value reached 136.2 billion dollars.[50] On the economic front, Singapore is actively working to integrate China into a framework of regional economic interdependence. The underlying idea is that economic integration and interdependence with other regional powers would signal to China that cooperation yields far greater benefits than attempting to expand its own sphere of influence.[51] China’s deep economic engagement helps maintain the status quo for Singapore, which is the country’s top priority given its limited resources and strained geographical position.

Singapore demonstrates a hedging strategy by not only seeking economic benefits from cooperation with China but also actively preparing for risks and uncertainties posed by China’s regional influence. The term “preparation” is used because a nation employing a hedging strategy anticipates that the status quo will remain stable, at least in the short term. While Singapore benefits significantly from trade and business cooperation with China, it remains deeply concerned about China’s growing ambitions in the South China Sea and its potential naval expansion in the region. Singapore is a small city-country with limited resources that strongly depends on international trade and energy imports to ensure sustainable resource supplies for long-term development. Maritime stability is Singapore’s most prioritized interest. As a result, Singapore closely monitors China’s expanding presence in its waters and remains wary of the potential for Chinese dominance, which could jeopardize its maritime freedom and security.[52] Although Singapore adopts a neutral stance on territorial disputes, it emphasizes that freedom of navigation and the security of sea lanes are crucial for its economy and security, and therefore non-negotiable. In 2011, when China’s actions in seas claimed by Vietnam and the Philippines threatened maritime stability, Singapore lodged a strong complaint with Beijing.[53] During the 2016 South China Sea arbitration, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong publicly endorsed the Philippines.[54] These actions again reflect Singapore’s priority of safeguarding maritime stability.

Singapore has enhanced its military cooperation with the U.S. to counter China’s rising regional power. Key measures include hosting U.S. littoral combat ships on a rotational basis, deploying U.S. P-8 Poseidon aircraft, and expanding joint military exercises like Pacific Griffin.[55] In 2019, the U.S. was granted continued access to Singapore’s air and naval bases until 2035.[56] These steps strengthen security ties with the United States, helping maintain a balance of power in the region. Singapore is strategically leveraging great power rivalry and China’s rise—particularly its economic growth—to its advantage. By adopting the strategy of hedging, Singapore maintains economic interdependence and military cooperation while also preserving the status quo and regional balance of power.

Vietnam’s Strategy amid China’s Power Projection in the Region

In comparison to Singapore, Vietnam has adopted a policy of soft balancing against China. Vietnam’s economic relationship with China is characterized by complexity and controversy, rather than being purely beneficial. While many ASEAN countries have profited from China’s economic growth, for Vietnam, this growth posed more challenges than advantages. The two countries compete directly in the global export market, and Vietnam faces a persistent trade deficit with China, which undermines the market share of its domestic products.[57] Furthermore, Chinese investments have fallen short of expectations, as Chinese firms in Vietnam often employ Chinese migrant workers, disrupting the local labor market and limiting job opportunities for domestic citizens.[58] On the security front, due to the difficult historical relationship with China, most Vietnamese political elites remain deeply distrustful of China and skeptical of its ambitions for regional hegemony.[59] Vietnam’s concerns have been reinforced in recent years by China’s growing power projection, geographical proximity, and the ongoing South China Sea dispute—all of which contribute to the perception of China’s rise as a security threat. In response, Vietnam has consistently sought to internationalize the South China Sea issue, advocating for multilateral negotiations.

Vietnam has taken several steps to strengthen its partnership with the United States as part of its strategy to counter China’s growing influence in the region. Vietnam has aligned itself with the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Strategy, which aims to challenge China’s power projection and safeguard regional stability.[60] Both countries emphasize the peaceful resolution of disputes through international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to address conflicts in the South China Sea.[61] On the security front, Vietnam and the United States engage in non-combat military exercises, capacity-building programs, and joint training initiatives to enhance maritime security and ensure freedom of navigation. Vietnam views closer cooperation with the United States as a strategic choice, recognizing that the U.S. is the only power capable of containing China’s military ambitions.[62] However, Vietnam carefully avoids over-reliance on any single power, prioritizing the enhancement of its own military capabilities to ensure strategic autonomy. Vietnam has not only employed a strategy of soft balancing to contain China but also asserts its agency by leveraging great power rivalry to safeguard its national interests. It has demonstrated a longstanding commitment to resisting external aggression by building military capacity while strategically partnering with other powers without forming formal alliances. For instance, Vietnam purchases military equipment from Russia while maintaining warm ties with the United States, which offers leverage against Beijing without compromising its independence.[63] By strengthening its defense capabilities and cultivating a positive international image through diplomatic engagement, Vietnam increases the costs of potential aggressors and deters hostile actions. In this way, Vietnam is not merely a passive actor caught between major powers, but rather a proactive player that strategically navigates great power competition to advance its national interests.

Cambodia’s Strategy amid China’s Power Projection in the Region

Cambodia has attempted to cultivate a mutually beneficial relationship with China and gradually moved from hedging between great powers to aligning more closely with Beijing. Cambodia does not have major political and regional disputes with China and thus seeks to leverage China’s growing influence in the region to gain advantages. China is Cambodia’s largest foreign aid donor. In 2007 and 2008, Beijing invested $600 million and $260 million, respectively, primarily for Cambodia’s infrastructure projects such as roads, highways, and irrigation systems.[64] These funds are expected to contribute to the construction of over 1,500 kilometers of roads and bridges in the country.[65] The differences in economic expectations and policies toward China between Vietnam and Cambodia can be largely attributed to security concerns.[66] Vietnam, due to its proximity to China and the ongoing South China Sea dispute, has declined China’s offer to build a high-speed rail network in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City for security reasons. In contrast, China has become Cambodia’s primary aid provider and a crucial investor. In fact, when the Philippines and Vietnam sought to challenge China’s dominance over the South China Sea by bringing the issue to the ASEAN negotiating table, Cambodia took a different stance. Cambodia argued that ASEAN should not serve as a forum for resolving the dispute and that the issue should be addressed bilaterally.[67] Cambodia also supported China’s rejection of the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) ruling in favor of the Philippines in July 2016, calling the decision “the worst political collusion in the framework of international politics.”[68] This alignment underscores Cambodia’s strategic prioritization of economic development and political loyalty to China over regional solidarity and multilateral dispute resolution within ASEAN.

Conclusion

By analyzing how Southeast Asian countries have navigated under the competing influences of China and the U.S. in the region, I have shown that small-size nations can effectively manage to maneuver by cultivating an amicable and flexible relationship with both sides without firmly choosing to stand with either side. Southeast Asian countries maintain diverse regional and economic ties with China, which significantly influence the variations in their foreign policies toward Beijing. Singapore is a great example of a hedging practitioner—its strategy is highly adaptable, enabling the country to maximize economic gains while maintaining security vigilance and preparing for potential external threats. Given its limited resources and strategic geographical location, Singapore must foster strong relationships with neighboring countries while maintaining robust military cooperation with the U.S. This approach helps prevent a power vacuum in the Asia-Pacific, which could lead to competition and conflicts among regional powers, while also addressing concerns over China’s expanding power projection and growing ambitions in the South China Sea. Vietnam, by contrast, employs a soft balancing strategy due to its geographical proximity to China and its strategic stakes in the South China Sea. However, Vietnam avoids over-reliance on any single great power, instead prioritizing the development of independent defense capabilities while fostering a warm relationship with the U.S. and other nations. This strategy gives Vietnam leverage against Beijing whilst preserving its sovereignty. In contrast, Cambodia has gradually shifted from hedging to bandwagoning, increasingly aligning with China on key issues like the South China Sea dispute. Cambodia views Beijing as a more important partner that better aligns with its national interests than the United States. This is because Cambodia holds positive economic expectations about their trade relationship with Beijing, and due to its geographical location, perceives China’s rise as posing minimal security threats to the region. The range of responses displayed by Southeastern countries ultimately demonstrates that smaller nations are able to adapt their strategies in a multitude of ways to develop a more flexible foreign policy, even when caught between the influences of great powers.

Lydia completed her undergraduate studies in Economics and Contemporary Asian Studies and is now pursuing a graduate degree at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. Her primary research interests include comparative colonialism in Asia, alternatives to Western democracy and neo-liberal models, and femininity in East Asia. Through her work with Synergy, she hopes to shed light on Asia’s diverse and often overlooked stories, while advocating for interdependence and solidarity across the Asian subcontinent.

Bibliography

Acharya, Amitav. “Seeking Security in the Dragon’s Shadow : China and Southeast Asia in the Emerging Asian Order.” Home, January 1, 1970. https://dr.ntu.edu.sg/handle/10220/4446.

Bert, Wayne. “Chinese Policies and U.S. Interests in Southeast Asia.” Asian Survey 33, no. 3 (March 1, 1993): 317–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645254.

Chen, Ian Tsung-Yen, and Alan Hao Yang. “A Harmonized Southeast Asia? Explanatory Typologies of ASEAN Countries’ Strategies to the Rise of China.” The Pacific Review 26, no. 3 (July 2013): 265–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2012.759260.

Cheng-Chwee, Kuik. “The Essence of Hedging: Malaysia and Singapore´ s Response to a Rising China.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 30, no. 2 (August 2008): 159–85. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs30-2a.

Ciorciari, J. D. “The Balance of Great-Power Influence in Contemporary Southeast Asia.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 9, no. 1 (October 28, 2008): 157–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcn017.

Cuong, Nguyen Manh, Kaddour Chelabi, Safia Anjum, Navya Gubbi Sateeshchandra, Svitlana Samoylenko, Kangwa Silwizya, and Tran Nghiem. “US-China Global Competition and Dilemma for Vietnam’s Strategic Choices in the South China Sea Conflict.” Heritage and Sustainable Development 6, no. 1 (May 23, 2024): 349–64. https://doi.org/10.37868/hsd.v6i1.550.

Doung, Chandy, William Kang, and Jaechun Kim. “Cambodia’s Foreign Policy Choice during 2010 to 2020: From Strategic Hedging to Bandwagoning.” The Korean Journal of International Studies 20, no. 1 (April 30, 2022): 55–88. https://doi.org/10.14731/kjis.2022.04.20.1.55.

Emmerson, Donald K., David M. Lampton, Selina Ho, Cheng-Chwee Kuik, and Yun Sun. “The Deer and the Dragon: Southeast Asia and China in the 21st Century.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 42, no. 3 (December 10, 2020): 425–30. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs42-3e.

Goh, Evelyn. “Great Powers and Hierarchical Order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing Regional Security Strategies.” International Security 32, no. 3 (January 2008): 113–57. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.113.

Nedić, Pavle. “Hedging Strategy as a Response to the United States-China Rivalry: The Case of Southeast Asia.” The Review of International Affairs 73, no. 1185 (2022): 91–112. https://doi.org/10.18485/iipe_ria.2022.73.1185.5.

Lake, David A. “Domination, Authority, and the Forms of Chinese Power.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 10, no. 4 (2017): 357–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pox012. Nedić, P. (2022). Hedging strategy as a response to the United States-China rivalry: The case of southeast asia. The Review of International Affairs, 73(1185), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.18485/iipe_ria.2022.73.1185.5

Ott, Marvin. “Southeast Asia’s Strategic Landscape.” SAIS Review of International Affairs 32, no. 1 (2012): 113–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2012.0003.

Ross, Robert S. “Balance of Power Politics and the Rise of China: Accommodation and Balancing in East Asia.” Security Studies 15, no. 3 (September 2006): 355–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636410601028206.

Roy, Denny. “Southeast Asia and China: Balancing or Bandwagoning?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 27, no. 2 (August 2005): 305–22. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs27-2g.

Shambaugh, David L. Where great powers meet: America & china in Southeast Asia. New York, NY, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. .

Simon, Sheldon W. “U.S. Interests in Southeast Asia: The Future Military Presence.” Asian Survey 31, no. 7 (July 1, 1991): 662–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645383.

Stromseth, Jonathan. “Don’t Make Us Choose: Southeast Asia in the Throes of US-China Rivalry.” Google Books, 2019. https://books.google.com/books/about/Don_t_Make_Us_Choose.html?id=0ILzzQEACAA

Wang, Albert. “中国如何把美国建立的反华组织,变成好朋友【东盟峰会·在现场】_哔哩哔哩_bilibili.” _哔哩哔哩_bilibili, October 20, 2024. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1QoyaYFEh1/?spm_id_from=333.337.search-card.all.click.

- Sheldon W. Simon, “U.S. Interests in Southeast Asia: The Future Military Presence,” Asian Survey 31, no. 7 (July 1, 1991): 662–75, https://doi.org/10.2307/2645383. ↑

- David L. Shambaugh, Where Great Powers Meet: America & China in Southeast Asia (New York, NY, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021). ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jonathan Stromseth, “Don’t Make Us Choose: Southeast Asia in the Throes of US-China Rivalry,” Google Books, 2019, https://books.google.com/books/about/Don_t_Make_Us_Choose.html?id=0ILzzQEACAAJ. ↑

- Evelyn Goh, “Great Powers and Hierarchical Order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing Regional Security Strategies,” International Security 32, no. 3 (January 2008): 113–57, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.113. ↑

- Stromseth. ↑

- Albert Wang, “中国如何把美国建立的反华组织,变成好朋友【东盟峰会·在现场】_哔哩哔哩_bilibili,” _哔哩哔哩_bilibili, October 20, 2024, https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1QoyaYFEh1/?spm_id_from=333.337.search-card.all.click. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Shambaugh. ↑

- Wang. ↑

- Wayne Bert, “Chinese Policies and U.S. Interests in Southeast Asia,” Asian Survey 33, no. 3 (March 1, 1993): 317–32, https://doi.org/10.2307/2645254. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Wang. ↑

- Bert. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Evelyn Goh, “Great Powers and Hierarchical Order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing Regional Security Strategies,” International Security 32, no. 3 (January 2008): 113–57, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.113. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Shambaugh. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Marvin Ott, “Southeast Asia’s Strategic Landscape,” SAIS Review of International Affairs 32, no. 1 (2012): 113–24, https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2012.0003. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Shambaugh. ↑

- David A Lake, “Domination, Authority, and the Forms of Chinese Power,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 10, no. 4 (2017): 357–82, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pox012. ↑

- Ott. ↑

- Amitav Acharya, “Seeking Security in the Dragon’s Shadow : China and Southeast Asia in the Emerging Asian Order,” Home, January 1, 1970, https://dr.ntu.edu.sg/handle/10220/4446. ↑

- J. D. Ciorciari, “The Balance of Great-Power Influence in Contemporary Southeast Asia,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 9, no. 1 (October 28, 2008): 157–96, https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcn017. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Goh. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Shambaugh. ↑

- Acharya. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Robert S. Ross, “Balance of Power Politics and the Rise of China: Accommodation and Balancing in East Asia,” Security Studies 15, no. 3 (September 2006): 355–95, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636410601028206. ↑

- Pavle Nedić, “Hedging Strategy as a Response to the United States-China Rivalry: The Case of Southeast Asia,” The Review of International Affairs 73, no. 1185 (2022): 91–112, https://doi.org/10.18485/iipe_ria.2022.73.1185.5. ↑

- Ian Tsung-Yen Chen and Alan Hao Yang, “A Harmonized Southeast Asia? Explanatory Typologies of ASEAN Countries’ Strategies to the Rise of China,” The Pacific Review 26, no. 3 (July 2013): 265–88, https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2012.759260. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Kuik Cheng-Chwee, “The Essence of Hedging: Malaysia and Singapore´ s Response to a Rising China,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 30, no. 2 (August 2008): 159–85, https://doi.org/10.1355/cs30-2a. ↑

- Chen and Yang. ↑

- Cheng-Chwee. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Nedić. ↑

- Goh. ↑

- Chen and Yang. ↑

- Nedić. ↑

- Chen and Yang. ↑

- Nedić. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Chen and Yang. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Denny Roy, “Southeast Asia and China: Balancing or Bandwagoning?,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 27, no. 2 (August 2005): 305–22, https://doi.org/10.1355/cs27-2g. ↑

- Cuong, Nguyen Manh, Kaddour Chelabi, Safia Anjum, Navya Gubbi Sateeshchandra, Svitlana Samoylenko, Kangwa Silwizya, and Tran Nghiem. “US-China Global Competition and Dilemma for Vietnam’s Strategic Choices in the South China Sea Conflict.” Heritage and Sustainable Development 6, no. 1 (May 23, 2024): 349–64. https://doi.org/10.37868/hsd.v6i1.550. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Emmerson, Donald K., David M. Lampton, Selina Ho, Cheng-Chwee Kuik, and Yun Sun. “The Deer and the Dragon: Southeast Asia and China in the 21st Century.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 42, no. 3 (December 10, 2020): 425–30. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs42-3e. ↑

- Chen and Yang. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Chandy Doung, William Kang, and Jaechun Kim, “Cambodia’s Foreign Policy Choice during 2010 to 2020: From Strategic Hedging to Bandwagoning,” The Korean Journal of International Studies 20, no. 1 (April 30, 2022): 55–88, https://doi.org/10.14731/kjis.2022.04.20.1.55. ↑

- Ibid. ↑