On November 22, 2024, the Munk School of Global Affairs and Foreign Policy hosted a screening of the film Survey City, sponsored by the Asian Institute’s Center for South Asian Studies. The speakers included Dr. Matt Birkinshaw, Tarini Manchanda, and Dr. Sanjay Srivastav. Dr. Birkinshaw is a Research Fellow at the Department of Anthropology and Sociology in the School of Oriental and Asian Studies at the University of London. His research interests in the politics of urban infrastructure, technologies and environments in South Asia aided the filmmaking process. Tarini Marchanda works in New Delhi, with local communities demanding changes in environmental law and social movements. With a background in Sociology and Environmental Policy, her films have been at residencies, festivals and universities across North America, Europe and India. The desire to solve social problems led to her interest in constructing truth and irony through visuals. Dr. Srivastav is a British Academy Global Professor at the University of London’s School of Oriental and Asian Studies. His key publications include ‘Constructing Post-colonial India. National Character and the Doon School; ‘Passionate Modernity. Sexuality, Class and Consumption in India’; ‘Entangled Urbanism. Slum, Gated Community and Shopping Mall in Delhi in Gurgaon’, and ‘Masculinity and the Post-national City. Streets, Neighbourhoods, Home and Consumerism’.

The screening of the film began with a brief preview of the research process and purpose behind the film. The triad discussed the transparency and efficiency of the bureaucracy and government implementation of technology as fundamental to their interest in developing the film. They further explored their motive in dissecting the theoretical idea of a state for the expansive diversity of communities in India.

The film zoomed out from the quaint sounds of bustling New Delhi to the local basti (slum). The narrator gave a brief overview of the residents of the basti – recycling/disposal workers who have lived in the area since migrating from neighboring states a few decades back. Stills of women working together in the open to sort through large swaths of recyclables set a firm concept of this community as a hard-working, low-income one. Although the opening dialogues of the residents gave a glimpse into their daily life as being naturally hectic, there was a sense of discontent present.

Bringing the major issue to light was a welfare worker: Shakeel. He introduced himself as part of a social organization that attempted to permanentize the basti-dwellers’ homes through cooperation with the government. Despite this civic support, he singled out bureaucratic inefficiency as the major issue that prevented these residents from getting their home certificates in time. He described how the government would conduct surveys in these bastis to get their homes certified, but their inefficiency was of such magnitude that they would conduct multiple surveys in consecutive months. He explored how the people had no avenues for grievance as they were themselves unaware of what they could do. In including his narrative on the bureaucracy’s inefficiency, the film developed the core issue that lay at the center of this story.

Following Shakeel’s narrative was a working mother – Ayesha – who had dwelled in this basti since she moved there a few decades back as a newly-wed. Despite the countless surveys, she said that they were yet to receive any certification of their home. She further complained that whenever the government worker would come to conduct a survey, they would explain very little, which left the basti-dwellers uncertain.

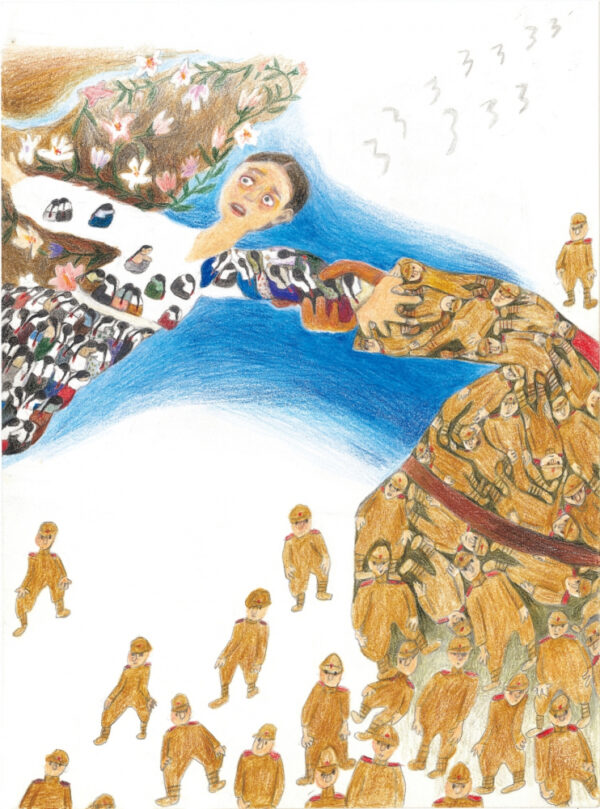

As others chimed in, they explored another issue that plagued the community’s ability to receive certifications: technology. With growing digitization in India since the 2019 election, the dwellers complained about how they were unaware of what the shanty ID and OTP (one-time passcode) were and how they were to be used, as they were used to the physical communication from before. Adding to this issue was the selectiveness of governments; the dwellers furthered how the government would only come during election season to gain votes. This would lead to some dwellers getting home certifications, but many remained without one.

During the filming, a major discovery was made by Shakeel’s organization: some thousand certificates had already been made for this basti, but were reported lost until a team member from their organization found them. While the organization began to distribute these certificates to the dwellers, a new, major revelation became known: some of these government workers would contract others to contract people to do these surveys. This meant that not only did the dwellers not know what the surveys were for, but the surveyors were unaware of what they were surveying either.

As the film shifted out from the multichromatic scheme to a monochromatic one, a bitter truth laced through the conscience of the screening’s attendees: the bureaucracy’s inefficiency was a core issue in India despite the rise in technology.

With the conclusion of the film, the speakers opened up a post-film discussion on key components. Notably, a dimly hopeful message of how common civilians could play a key role in increasing government accountability through civic participation and social work was developed.

Ankur Phadke is a second-year undergraduate student pursuing a major in International Relations and Public Policy, and a minor in Political Science. His research interests center on incorporating political theory, political actions, and human behavior to explain diplomatic relations and socioeconomic development in South Asia.