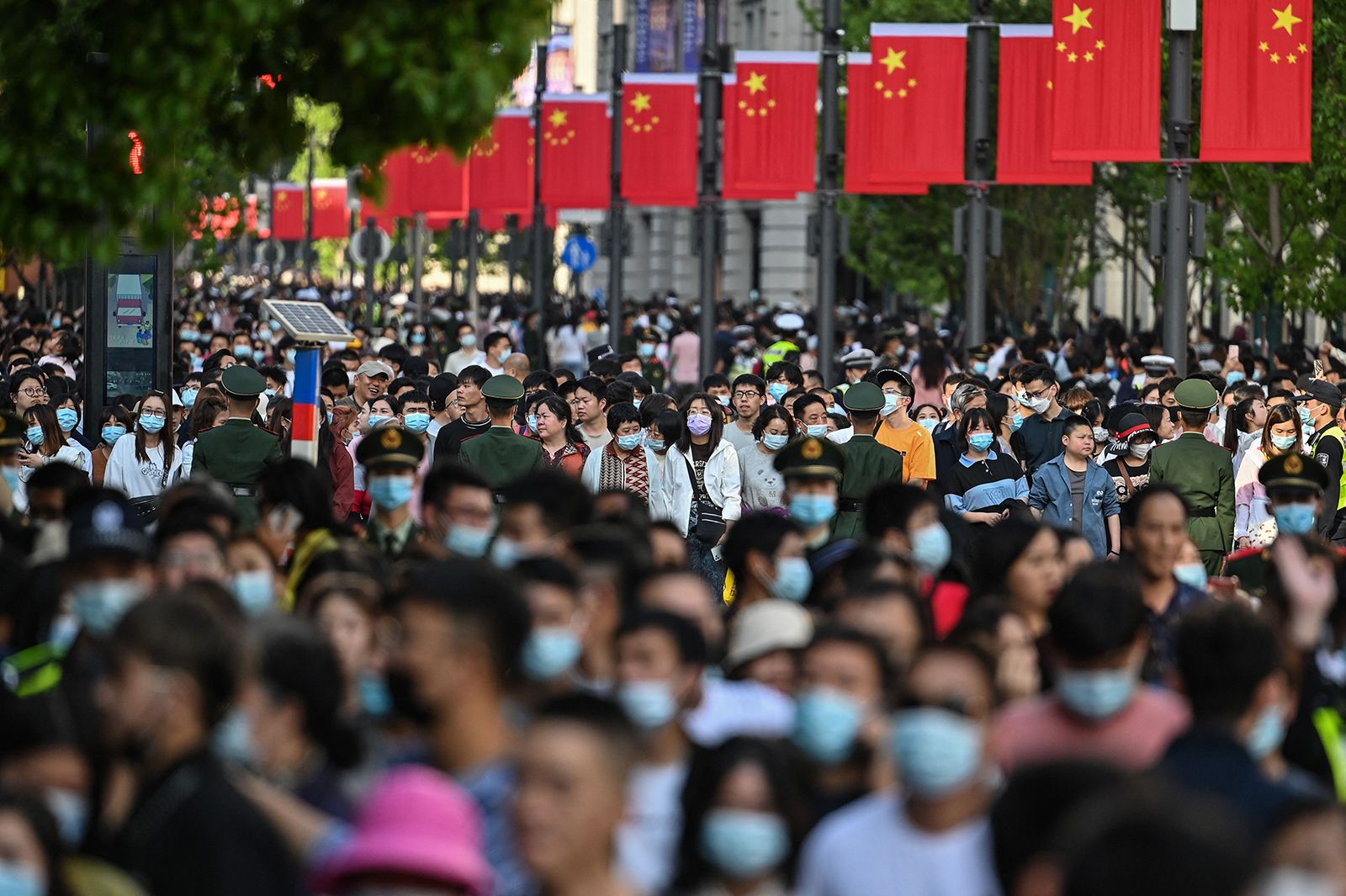

According to CNN Hong Kong, in 2022, the number of marriage registrations in China fell to its lowest level since 1979, accompanied by a population decline of 850,000 people. This trend speaks to the reality that younger generations in China are now far less inclined to marry and have children compared to their parents’ generation, which adhered to the traditional belief of “starting a family before building a career.” In response to declining birth rates, China’s National People’s Congress amended the Population and Family Planning Law in August 2021. The revised law encourages married couples to have up to three children, with the government offering financial support to ease the costs of raising a family. However, despite these efforts and societal pressures from parents and relatives who hold strong, positive views on marriage, many young people remain reluctant, and even hostile, towards it. What, then, has driven this generational shift in attitudes toward marriage in China?

The transition from a planned economy with stable employment to a neoliberal economy characterized by precarity and uncertainty has significantly influenced contemporary Chinese views on marriage. During the 1950s through the late 1970s, under China’s planned economy, the state guaranteed employment, provided standardized housing, and ensured relatively equal incomes for urban residents. This system—often referred to as the “iron rice bowl”—offered Chinese people a predictable and stable life path with minimal financial uncertainty, as the government managed most aspects of social and economic life. In other words, for the older generation, despite low incomes and universally impoverished living conditions, the stability of steady earnings allowed them to plan their expenditures accordingly. Life was modest, but they had a predictable and secure future.

As China transitioned to a market-oriented economy under Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up policies, the previous guarantees of stable employment and government-provided housing were replaced by flexible job opportunities subject to market forces. This shift introduced significant challenges for young people, including fierce job competition, soaring housing costs, and economic volatility. These factors have created an uncertain future for today’s young Chinese, whose labor—unlike that of their parents and grandparents—lacks guaranteed market rewards, as they face the constant risk of layoffs during economic downturns. Many young people feel they are working hard for a future more fraught with anxiety than that of their parents. As a result, they are determined not to subject their children to the same struggles they currently endure.

In addition to the economic structures, the introduction of neoliberalism has fundamentally shifted perceptions of responsibility and subsequently marriage values by bringing Western ideals and values. Many people from older generations struggle to understand the pressures that having children places on young people today, as their values stem from the belief that even during times of hardship, such as 1960s China, raising children was manageable. Given current living standards, they see no reason why continuing the family line and fulfilling social responsibilities should not remain expected. This perspective suggests that they prioritize the responsibility of having children over the responsibility of raising them. In contrast, today’s young Chinese place greater emphasis on personal responsibility within marriage. They focus more on individual emotions and experiences rather than traditional societal or national duties. When considering marriage, this sense of self-responsibility extends to carefully contemplating the well-being of their future children. For instance, they might ponder: “If I bring a child into this world, will they be happy?”—a question that the older generation seldom considered. This is because traditional Chinese marriage value is deeply influenced by Confucian principles, where marriage was primarily viewed as a moral duty, with parents serving as the main authority figures.1 A traditional Chinese saying, introduced by Mencius, states: “不孝有三,无后为大” (“Among the three forms of unfilial deeds, the most serious is to have no offspring”).2 Under the influence of Confucian teachings, marriage and parenthood were regarded as societal obligations, prioritizing social functions and family responsibilities over personal choice and the freedom to love. Today, as young people are increasingly exposed to Western ideals that focus on individual autonomy and self-expression, they are shifting toward a perspective that life should center on personal happiness rather than fulfilling the expectations of others. When considering marriage, one should first focus on their own emotional experiences and sense of happiness, and then consider the expectations of others. For example, continuing the family line is an expectation of others, but whether to have children should be based on personal desire and happiness.

Lydia completed her undergraduate studies in Economics and Contemporary Asian Studies and is now pursuing a graduate degree at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. Her primary research interests include comparative colonialism in Asia, alternatives to Western democracy and neo-liberal models, and femininity in East Asia. Through her work with Synergy, she hopes to shed light on Asia’s diverse and often overlooked stories, while advocating for interdependence and solidarity across the Asian subcontinent.

Footnotes

- Cheng, M. (2021). A comparison between traditional Chinese and Western marriage culture. Journal of Higher Education Research, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.32629/jher.v2i3.344 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

Bibliography

Cheng, M. (2021). A comparison between traditional Chinese and Western marriage culture. Journal of Higher Education Research, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.32629/jher.v2i3.344

Lukacs, G. (2015). Labor Games: Youth, work, and politics in East Asia. Positions: Asia Critique, 23(3), 381–409. https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-3125799

Yeung, W.-J. J. (2016). Paradox in marriage values and behavior in contemporary China. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 2(3), 447–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150×16659019