ABSTRACT

With the increasing movement toward a Taiwan-based politics, there has also been a simultaneous fixation on the role of the state of the Republic of China in Taiwanese politics. In conversation with the normative arguments made by scholars on the democratization of Taiwan during the Lee Teng-hui presidency, this article discusses how the historical processes of Sinicization figure Taiwan nationalism as the underlying ideology upon which the identification with Taiwan is bound. By contesting the impetus and enculturation of the Wild Lily student movement organizers through an analysis of their calls for democratization and nationalism vis-à-vis the subsequent actions of Lee’s administration, I show how the increasing call for a Taiwan nationalism is underlined by a simultaneous yet more silent institution of Sinicization in official political ideology. This article uses primary sources and scholarly works and is primarily a review of the literature on the issue of Sinicization in Taiwanese politics but centres the issue of relationality between the two Chinas. This article further opens questions on China studies more generally, however, it is predominantly focused on the orientating role of culture in Sinosphere politics.

KEYWORDS: China, Taiwan, Nationalism, Democracy, Lee Teng-hui

Introduction

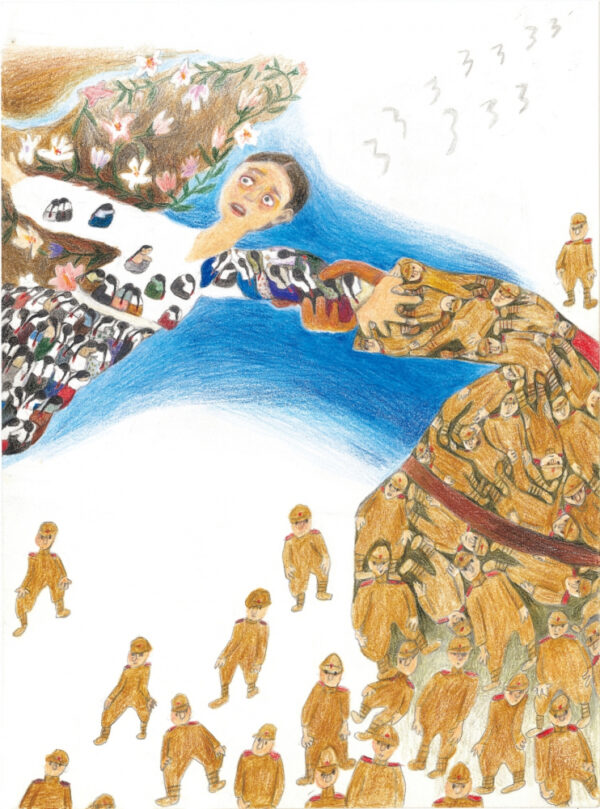

Wu Zhuoliu’s Orphan of Asia (1945) is an autobiographical account of its author and tells the story of Hu Taiming, a Taiwanese-born Chinese who moved to Taiwan before 1949 (本土人, benturen). Raised in the classical Chinese scholar-gentry tradition but educated in the colonial Japanese educational system, Hu finds himself excluded from his family and his community. Wu tells a story of converging cultural systems and foreign hegemony,and his story has now become a normative metaphor for Taiwan’s position within East Asia as the site of Chinese creolization and interaction with various Indigenous groups, Japanese occupation and colonization, and later an authoritarian fascist government under Chiang Kai-shek who ruled in the name of “China.” Throughout these periods, “Chinese” culture has been present in Taiwan and has been mobilized against Japanese aggression. However, it has also found itself as the object of objection to and identification with amidst a growing movement toward identifying with Taiwan, a process also known as Taiwanization. In addition, there is a seemingly more aporic quandary around the idea of “China,” where Sinicization, or the process of making and performing “Chinese,” continues to be a dominant system of knowledge in Taiwan. Even though the idea of China is increasingly pushed back against, the idea of Taiwan is figured by a performed “China.” This dilemma between identification with Taiwan and the process of “making Chinese” amidst the fluidity of the idea of “China” is what interests me, so I ask whether Sinicization exists in a political climate increasingly oriented toward Taiwan independence and nationalism, and if so, how? To that end, Sinicization figures Taiwan nationalism as an underlying ideology from which Taiwanization stems, not rupturing Taiwanization.

I am not interested in debates about whether Taiwan belongs to China or is its own sovereign nation-state; rather, I am interested in how Sinicization underlies figurations of Taiwan nationalism, regardless of the question of Taiwan’s sovereignty. Hui-ching Chang and Rich Holt write that “Taiwanese culture has its foundation in China, and the impact of Chinese culture will not disappear simply because people claim it to be the case.”[1] It is from this articulation of duality that I push back against the binarization of the Taiwan/China debate, which does not adequately capture the process of Sinicization in Taiwan. The impetus for this paper is to move beyond the debate of whether Taiwan is China and to focus on how Taiwanization and Taiwan nationalism is figured by Sinicization. This paper is primarily concerned with political and cultural developments in Taiwan under the leadership of Lee Teng-hui during the Wild Lily student movement and the transition toward democracy in figuring a Taiwan nationalism. This paper begins by examining normative arguments about Taiwan nationalism made by Edward Friedman, an American scholar of China formerly at the University of Wisconsin, to produce a non-normative account of Taiwan nationalism as figured by Sinicization. It then makes arguments for the role of Sinicization in figuring political currents across the Taiwanese political spectrum and the performance of Sinicization.

Friedman argues that Sinicization in Taiwan is figured against the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) figuration of “Chineseness” in Taiwan.[2] This argument has been crystallized in normative Western politics, and while it has some weight, in conversation with other scholarship on nationalism, Friedman’s argument demonstrates serious gaps in the normative assumptions about the role of Sinicization figured in Taiwan nationalism. First, Friedman suggests that the arrival of Chinese people and the creolization of Chinese culture in Taiwan is the basis of Taiwan’s nationalism today. He argues that Taiwan nationalism is the result of creolized Chinese people and their democracy; because the two cultures are different, Taiwan cannot be Chinese. He discusses Chiang Kai-shek’s program of Sinicization that constructed both Chinese creoles and non-creoles as Chinesein the eyes of the state,[3] yet both of these groups, benturen and waishengren (外省人), migrants from the Chinese Mainland who arrived after 1949, reacted and did not accept their figuration as “Chinese” because of the CCP.[4] This normative statement suggests that the rule of the Kuomintang (KMT) figured “Chinese” as figured by the government in Beijing. While this claim is substantiated by Benedict Anderson’s argument of creole nationalism, whereby creoles “developed […] early conceptions of their nation-ness,”[5] the argument for creolization as the basis of nationalism does not address how Sinicization practiced by the KMT gave rise to the memorialization of an imagined “China” based upon the historical fetishization of imperial “China,” and not CCP nationalism. Secondly, Friedman argues that Taiwan nationalism exists, because Taiwan nationalism is backed by its moral superiority in an amoral, power-fetishizing world. He writes that the government in Taipei did not focus on how the largely amoral international world rewarded power and not virtue. It is the power of an authoritarian China and not Taiwan’s democratic virtues which has shaped how the world community understands or misunderstands democratic Taiwan and Chinese Power commands attention in international relations.[6]

The practice, and even triumph, of Taiwan nationalism against international conditions suggests that Taiwan nationalism is a response to global pressures. This almost fits a functional definition of nationalism, as posited by Chalmers Johnson, who writes that nationalist movements can be identified by “specific physical pressures that by acting upon given political environments give rise to nationalist movements.”[7] Yet, this argument does not take into account how the production of “China” in Taiwan nationalism during the Lee Teng-hui presidency accepted the role of Mainland Chinese power while simultaneously making space for Taiwan qua the Republic of China (ROC) in international diplomacy as a result of the discursive location of “China.” Friedman’s argument sets out a binary whereby the world must accept either China or Taiwan in diplomacy, and this binary is the basis for “real” diplomacy and thus “real” legitimacy. Yet, in practice, most nations worldwide conduct diplomacy and business with both states and, even more interestingly, do so by merely ignoring that Taiwan is officially the ROC. Thus, international pressures from China as the impetus for Taiwan nationalism can be considered a partial argument, but ambiguity is also a way of conducting international relations. Finally, Friedman sums up KMT electoral viability in a post-dictatorship Taiwan by claiming that KMT victories resulted from a poorly guided nationalist movement by the Democratic Peoples’ Party (DPP) and Taiwanese people’s dominant political concerns about economic gains. He writes that the KMT was able to claim this mantle as “KMT leaders hoped that China’s economy was like East Germany’s […] it was rotten and would soon collapse.”[8] Implicating the failure of the alternate DPP in electoral politics as the reason for KMT victories necessarily marginalizes the role of Sinicization in electoral politics and the nostalgia around the idea of “China,” which constitutes a significant majority of Taiwanese electoral politics. It further deepens the binarization of identity politics in Taiwan by reinforcing a Taiwan/China divide in Taiwan’s failure to perform well against China. Ultimately, Friedman suggests that there are normative binaries in understanding the role of China in Taiwanese politics. My goal is not to argue for or against any of the normal and/or pathologized positions set out by how these binaries are encountered in relation to individuals’ embodied ontology, but rather to question their construction in the first place. With this in mind, I develop a working definition of Sinicization and then understand how it enables the articulation of identification with Taiwan.

Sinicization has a long history in Taiwan, and while it is interesting to know the forms it has taken throughout its practice, I am particularly interested in its application during the presidency of Lee Teng-hui. To that end, I briefly touch upon Sinicization’s practice during the Chiang Kai-shek dictatorship (1948-1975) and the Chiang Ching-kuo presidency (1978-1988) to arrive at a more precise definition of Sinicization as the KMT practiced it, before I delve into the politics of the Lee Teng-hui presidency and the Wild Lily student movement. The 228 Uprising in 1947 was the catalyst for Chinese nationalism, expressed through Sinicization, and the subsequent authoritarian martial law period known as the White Terror. This period imposed a national language (国语, Guoyu) based on standard Mandarin and the replacement of all “Japanese” culture with “Chinese” culture, which was represented by Chiang’s government.[9] These movements were designed to stamp out Taiwanese cultural movements, which, since the 1920s, had engaged in cross-strait political activities associated with socialism, anarchism, and communism.[10] Yet by 1986, Chiang Ching-kuo had begun to adopt reforms that brought in more Taiwan-born political leaders, with 7 out of 11 provincial commissioners being Taiwanese.[11] These areas of practice lead me to work with Sinicization as a practice of performing an imagined Chinese culture/“China,” an anti-Communism that figures the Peoples’ Republic of China (PRC) as a perversion of “China,” while also ensnaring the geographic bounds of “Taiwan” and identification with “Taiwan” as a way of fortifying the practice of “China.” In what follows, I argue that the practice of Sinicization during the Lee Teng-hui presidency figures Taiwan nationalism by upholding the centrality of the idea of China and through the performance of an imagined China by naming Taiwan. I centre Lee Teng-hui’s support for the Wild Lily student movement in this argument in order to move beyond the normative notion that de-Sinicization gave rise to Taiwan nationalism and to demonstrate the critical role of Sinicization in figuring Taiwan nationalism.

The Wild Lily Student Movement: Naming Taiwan, Performing “China”

The 1990 Wild Lily student movement was a six-day sit-in demonstration in Taipei’s now renamed Liberty Square. The goal of the movement was a full and direct representative democracy that was localized in Taiwan. The movement was supported by DPP/Tangwai (党外, dangwai) leaders, and it ultimately gained the support of then-President Lee Teng-hui, who promised free elections for members of the National Assembly and the Presidency by 1996. This coincided with structural changes to the government that enabled the identification with Taiwan, known as Taiwanization. With this in mind, I demonstrate that the identification with Taiwan is not the result and/or success of the process of de-Sinicization but is actually enabled by political transformations that uphold the centrality of the idea of “China.” I pay specific attention to the ways that Sinicization figures identification with Taiwan through adherence to an imagined “China” in cultural and political production whereby all groups are asked to participate around China in discourse.

As a result of student activists, Lee Teng-hui’s incorporation of local Taiwanese people into the bureaucracy, alongside constitutional changes to remove Mainland Chinese seats from the National Assembly, did not result in de-Sinicization and democracy; instead, it expanded the political orientation around Sinicization and the idea of “China.” In 1996, the ROC National Assembly consisted of over 600 members representing constituencies in both Taiwan and Mainland China, which was a significant attribute because even if elections were free throughout the White Terror period, there would have been a marginal representation of people from Taiwan at best. In this context, localizing the National Assembly and demanding the direct election of representatives had been central to the 1980s activism of Tangwai members. However, this activist organization was done not on the basis of Taiwan independence but through the posturing of the activists as intellectuals while “becoming shrewd managers of resources, taking all alliances as transitory, and mobilizing all kinds of resources to fulfill their own (temporary) goals.”[12] In this way, when political elections opened up, the DPP, while messaging as a liberal-progressive party, was structurally figured similarly to the KMT. The DPP used its academic status to impress upon the electorate, who it saw as uneducated, the purity of academics that could essentially improve them as a “population,” whereas the KMT saw itself as civilizing the population in the image of a specific figuration of “Chinese” culture.[13] Both of these processes similarly used the discourse of “civilization” found within the ideology of Sinicization, resulting in a performance of Sinicization that incorporated the Taiwanese working classes into DPP and KMT party ranks in order to become the two most dominant political forces in Taiwanese electoral politics. Their shared structure was the result of their development within interpretive communities, which, “having been socialized into particular lines of interpretation,”[14] led to a shared understanding of organization on the basis of cultural logics organized by Sinicization. In this sense, Taiwanese politics during the transition period heralded by Lee in the name of the Wild Lily student movement was not merely a political debate between reunification and Taiwan independence, but one wherein Taiwanese people believed “that only the ROC in Taiwan—and not the People’s Republic—can represent them [Taiwanese people] both internally and on the international scene.”[15] Thus, Lee’s constitutional changes that enabled direct elections and the National Assembly’s shrinkage did not come out of the normative understanding whereby Taiwanese protestors pursued democracy and de-Sinicization; they employed Sinicization and its structuration of society to be politically viable under a new constitutional framework.

Amidst the expansion of a Sinicized political orientation within Taiwan’s political structures, a concurrent trend within the Taiwanese electorate and the increasing possibility of identifying with “Taiwan” and as “Taiwanese” was a current figured by Sinicization. In 1997, Lee oversaw further changes to the constitution that transformed the government in Taipei from a provincial Chinese government, representing the Taiwan Province of China, into an official seat of government for the ROC in Taiwan.[16] These changes were pragmatically done to avoid the problem of involution as Taipei hosted both the government of Taiwan Province and the ROC’s exiled government. Yet, the replacement of these governments with the singular ROC in Taiwan made it possible, in a legal and textual sense, to be of Chinese descent but identify as Taiwanese without any contradiction. This was possible as a result of signification; signs are composed of a signifier (image) and a signified (derived meaning). By taking the exiled government in Taipei out of exile, the ROC became a Chinese government that signified Taiwan. Thus, the 1997 constitutional changes made it possible to be both Chinese, in a sense of citizenship and belonging, while simultaneously identifying with Taiwan. This resignification simultaneously reinforced the signification of an imagined “China” in Taiwan that was epistemologically different from the “China” signalled by the Mainland, thus reinforcing the phenomenon of Two Chinas. In retrospect of the 1997 constitutional changes, Lee’s support of the 1990 Wild Lily student movement, in contrast to the Tiananmen Square affair one year prior, appeared to signal Two Chinas: one “China” in Taiwan signalled by democracy and identification with Taiwan, and the other signalled by the government in Beijing that was perceived to have effectively destroyed “Chinese” culture. Thus, identifying with Taiwan and calling for Taiwan nationalism did not only carry traces of protecting a “Chinese culture” that the Mainland had lost; it was also positioned to protect Taiwan from “China” while simultaneously claiming to be “China.” Regardless of whether Lee wanted to localize political processes in order to identify Taiwan as an independent state, the 1997 constitutional changes that legally brought the ROC government out of exile proliferated an identification with Taiwan bound to a specific figuration of a lost China Taiwan-based Sinicization produced.

The establishment of the official ROC government in Taiwan coincided with a simultaneous reformation of Taiwan’s relationship to the Chinese Mainland as a result of a redefinition of the ROC’s governed territories. Lee Teng-hui’s special state-to-state foreign policy to govern these new relations transformed Sinicization in Taiwan by reiterating the centrality of “Zhongguo” discourse, which is co-dependent upon the production, interpretation and entrenchment of Mainland China figured by Sinicization in Taiwan. “Zhongguo”is simultaneously a cultural and civilizational discourse that underlies the cultural and nationalist claims of both the ROC and the PRC governments. With the movement of the ROC government onto Taiwan in 1997, I see Lee Teng-hui’s policy pursuit of a “special state-to-state” relationship (literally one special state and one normal state having a relationship) as a way of doing “Zhongguo” that protected the ROC’s cultural claims while simultaneously opening up the interpretation of “Zhongguo” to produced knowledge about the PRC in Mainland China. In associating the newly democratic ROC on Taiwan as “Zhongguo,” Chang and Holt write that “democratization in modern Taiwan has led many to insist that [Taiwan’s] fate must not to be defined by ‘otherness.’”[17] With democratization as a performative signifier of a “normal” state in a “special” situation, the ROC could claim to be a temporally advanced “Zhongguo” under the auspices of the normative assumptions of capitalist modernity, which assumes the supremacy of liberal democracy and free market capitalism, while implicating Mainland China as “degenerate” and “backward” under the same terms of capitalist modernity. Thus, democratization was not actually a conscious choice done in order to reinforce Taiwanese independence but done to temporally implicate a specific figuration of a Mainland “Zhongguo”in lost time and produce a democratic Taiwan as a vibrant and viable “China” as a means of ensuring the survival of the ROC in a world where modernity is premised upon the idea of one-culture, one-state. Yet, the pursuit of ambiguity in defining relations between Taiwan and Mainland China meant that the ROC had to continuously produce and know the Mainland Chinese state as an “Other” in order to dominate it. By constructing Mainland China as the “Other,” Taiwan assumes the position of the advanced state who can then know “the Orient [Mainland China] as a body of knowledge.”[18] The use of a special state-to-state relationship policy led to the production of a body of knowledge that fatalistically produced a “degenerate” Mainland China which, contrary to normative assumptions about this relationship that signify increasingly separate ties, did not release Taiwan from the hold of China but further deepened the dependency and contingency of a “civilized” Taiwan as the occident on Mainland China. Lee Teng-hui’s foreign policy did not bring together two independent states that had a special and/or normal relationship; rather, it was a relationship that engendered “knowledge” as a stopgap to ensure the survival of the ROC on Taiwan by discovering the truth of Mainland China’s “degeneracy” that Taiwan could not achieve. Ultimately, perpetuating a Taiwan nationalism that is dependent upon Sinicization through Lee’s foreign policy was a fatalistic project that effectively transformed the terms of Sinicization by incorporating a produced body of knowledge that entrenched the “degenerate” Mainland China as the contingent variable of Taiwan’s nationalism.

With the binarization of the Chinas into degenerate/civilized entailed within Sinicization, cultural practices from the Wild Lily student movement and the presidency of Lee Teng-hui transformed to encapsulate the performance of a “free China.” Literature plays a vital role in nationalism, wherein “powerful new impulses for vernacular linguistic unification” and the economization of these vernaculars through print-capitalism ultimately spread national solidarities based on not just shared language but the production of a shared experience.[19] Throughout the 1980s, literature from Taiwan proliferated by centring the role of “originality and nativization,” yet this current in Taiwanese literature was not seen as individually Taiwanese, but as “Taiwan literature as a part or link of the Chinese literary tradition.”[20] This current in Taiwan literature encapsulated many incredibly influential movements in “Chinese” literature, including the tongzhi wenxue and the nüxing zhuyi wenxue movements that captured life’s specific conditions in the pre-democratic ROC. Within the democratization and Taiwanization movement, these pieces of literature perpetuated civilizational discourse that affiliated the movement for democracy with the advancement of Chinese civilization. Furthermore, the reception and interpretation of these works of literature by the educated classes synthesized the notion that, as a class, the educated (including students, members of the tangwai and DPP, as well as Taiwanese KMT members) saw themselves not as Taiwan independence leaders, but as performing a Free China of scholar-gentry “through layers of representation and translation.”[21] Thus, literature enabled the production of an imagined “Free China” that continued to uphold its cultural heritage, within a broader genealogy of Chinese literature, whereby educated elites engaged with Sinicized civilization discourse in order to push forth a localized democracy that constructed Taiwan as an always-already sovereign nation that has historically engaged with Chinese culture.

Conclusion

In this paper, I demonstrated that Sinicization figures Taiwan nationalism as the underlying ideology upon which Taiwan nationalism and Taiwanization take their forms and are bound. I demonstrated the issues with the normative arguments made about Taiwan nationalism, noting how they produce a system of binaries that are logically ordered by divisive rhetoric and the essentialization of a Taiwanese national culture that was epistemologically different from Chinese culture. Because of Taiwan’s history with creolization and authoritarian domination, it is difficult for indigenous cultures to be the same, so I asked how Sinicization, figured by the KMT under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo, enabled Taiwanization movements under Lee Teng-hui. I initially demonstrated that the calls for localizing the National Assembly in Taiwan continued the political orientation around Sinicization and the idea of “China” because of how Sinicization bound opposition parties and their success. I then demonstrated that the 1997 changes to the ROC constitution enabled an explicit identification with Taiwan, not in contrast to identification with China, because the replacement of the Taiwan Province government with the central government of the ROC in Taiwan enabled the identification with “Taiwan” as semiotically identifying with “China.” I then moved to demonstrate that these political changes continued to hold Taiwan nationalism within civilization discourse where Taiwan nationalism was just one form of Chinese civilization and that literature cemented Taiwan nationalism as a product of Sinicization. Returning to the Orphan of Asia metaphor that opened this paper, it is not merely that Taiwan is the culturally orphaned child of East Asia that has synthesized its many cultures, but rather that the hegemonic ideology of Sinicization underlies the production and interpretation of nativist and local cultures as a means by which Taiwan nationalism can be considered alive. While I have put forth that the Lee Teng-hui presidency and the Wild Flower student movement should not be seen as a rupture between these two “Chinas,” this paper is only an introduction to the way that Sinicization figures Taiwan nationalism.

Thomas Elias Siddall is a researcher at the University of Toronto’s Asian Institute and School of Cities and fourth-year student at the same institution. Their work primarily focuses on urbanisms and space, postsocialism, and migration through queer/Marxist perspectives.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. New York: Verso, 1983.

Cabestan, Jean-Pierre. “Specificities and Limits of Taiwan Nationalism.” China Perspectives 62(2008):1-17. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.2863.

Chen, Hsin-Hsing. “My Wild Lily: a self-criticism from a participant in the March 1990 student movement.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6, no. 4 (2005): 591-608.

Chang, Hui-Ching, and Holt, Rich. “Symbols in Conflict: Taiwan (Taiwan) and Zhongguo (China) in Taiwan’s Identity Politics.” Nationalism and Ethnic Policies 13, (2007):129-165.

Friedman, Edward. “Chineseness and Taiwan’s Democratization.” American Journal of Chinese Studies 16 (2009):57-67.

Hao, Zhidong. “Imagining Taiwan (1): Japanization, Re-Sinicization, and the Role of Intellectuals.” In Whither Taiwan and Mainland China: National Identity, the State and Intellectuals, 27-48. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010.

Johnson, Chalmers. Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1937-1945. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Tang, Xiaobing. “On the Concept of Taiwan Literature.” Modern China 25, no. 4 (October 1999): 379-422.

Weller, Robert. Resistence, Chaos and Control in China: Taiping Rebels, Taiwanese Ghosts, and Tiananmen. London: Macmillan, 1994.

[1] Hui-ching Chang and Rich Holt, “Symbols in Conflict: Taiwan (Taiwan) an Zhongguo (China) in Taiwan’s Identity Politics,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, v. 13 (2007), 149.

[2] Edward Friedman, “Chinesensess and Taiwan’s Democratization,” American Journal of Chinese Studies, v. 16 (2009), 57-67.

[3] Friedman, Chineseness and Taiwan,58.

[4] Friedman, Chineseness and Taiwan, 60.

[5] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, (New York: Verso, 1983): 50.

[6] Friedman, Chineseness and Taiwan, 62-63.

[7] Chalmers Johnson, Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1937-1945, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962), ix.

[8] Friedman, Chineseness and Taiwan, 62.

[9] Zhidong Hao, “Imagining Taiwan (1): Japanization, Re-Sinicization, and the Role of Intellectuals,” in Whither Taiwan and Mainland China: National Identity, the State and Intellectuals (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), 40.

[10] Zhidong Hao, “Imagining Taiwan,”33.

[11] Zhidong Hao, “Imagining Taiwan,”41.

[12] Hsin-Hsing Chen, “My Wild Lily: a self-criticism from a participant in the March 1990 student movement,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, v. 6 no. 4 (2005), 596.

[13] IBID.

[14] Robert Weller, Resistence, Chaos and Control in China: Taiping Rebels, Taiwanese Ghosts, and Tiananmen, (London: Macmillan, 1994), 21.

[15] Jean-Pierre Cabestan, “Specificities and Limits of Taiwan Nationalism,” China Perspectives v. 62 (2008), 2.

[16] Hui-ching Chang and Rich Holt, Symbols in Conflict, 140.

[17] Hui-ching Chang and Rich Holt, Symbols in Conflict, 145.

[18] Edward Said, Orientalism, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), 43.

[19] Anderson, Imagined Communities, 77.

[20] Xiaobing Tang, “On the Concept of Taiwan Literature,” Modern China, v. 25 no. 4 (October 1999): 383.

[21] Hsin-Hsing Chen, My Wild Lily, 594.