Abstract: This paper argues against the claim that despite plunder and exploitation, British colonialism had lasting benefits in South Asia; the assertion is incomplete and fails to account for the continuous consequences of the Partition Plan and its effect on ideology, society and governance in India and Pakistan. The Partition Plan of 1947 had extremely adverse effects on the nationalisms, extremist views and political trajectories of the Indian and Pakistani states. With particular attention to the colonial legacy of the Radcliffe Commission, this essay assesses the shortcomings, miscalculations and outright ignorance of British rule.

Keywords: Partition Plan, Radcliffe Commission, colonialism, extremism, Lord Mountbatten

On June 3rd, 1947 people in British India gathered around their radio sets across the country to hear the broadcast that would inform them of the departure of the British and the transfer of power to the Indian people. This announcement by Viceroy and Governor-General Louis Mountbatten partitioned the nation of India and created the nation of Pakistan on uncertain terms. While it was clear two entities existed, the terms of their partition were not detailed on June 3rd and would not be unveiled to the Indian people until after Pakistan’s and India’s independence was declared on August 14th and 15th 1947 respectively.[1] The task of partition and the creation of borders was treated with little precision or care and the consequences of it are still lived today. The Partition Plan of 1947 has essentially dictated the political relationship between India and Pakistan. There are many legacies of British colonialism that are varied in nature and in reach, but I will focus on one particular legacy – that of the Partition Plan. The claim that, despite plunder and exploitation, British colonialism had lasting benefits in South Asia is incomplete; it fails to account for the ongoing consequences of the Partition Plan and its effect on ideology, society and governance in India and Pakistan. In analyzing the Partition Plan, with focus on the case of Kashmir and Jammu, I will demonstrate that this one decision alone, the Radcliffe Commission and the Partition Plan, left behind Britain’s most consequential colonial legacy, which outweighs the benefits of any technological, legal or ideological creations that they may have left behind.

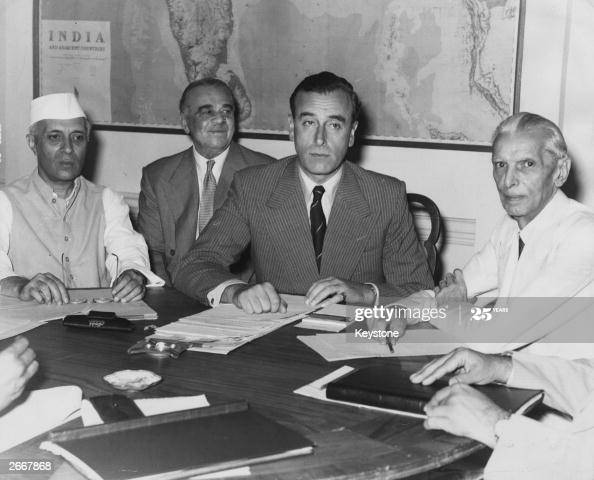

To understand Mountbatten’s announcement on June 3rd and the succeeding Partition Plan, it is important to discern who the main actors were and their role in the partition. Lord Mountbatten served as the last Viceroy of British India between March and August of 1947 and continued on as India’s Governor General until 1948.[2] Mountbatten’s first meeting with Jawaharlal Nehru, who would be the first Prime Minister of India, was characterized with respect and admiration – Mountbatten said that Nehru “struck me as most sincere.”[3] Nehru’s opinion on the Muslim League’s Muhammad Ali Jinnah influenced Mountbatten in that meeting and set the tone for the subsequent relationship between Mountbatten and Jinnah. As Stanley Wolpert writes, “Nehru’s negative assessment of Jinnah would never be erased from Mountbatten’s mind and did more damage to Pakistan…than had been realized.”[4] Lord Mountbatten’s main objective was making haste decisions about the future of India and his perspective was colored by his support for a united state instead of two separate states.[5] While Lord Mountbatten oversaw the partition of India, the particulars of the plan were left to a different British man – Sir Cyril Radcliffe. The skilled judge from London was appointed to the chairmanship of the boundary commissions in charge of negotiating the border between India and Pakistan.[6] The Congress and the Muslim League sent two members each to both the Punjab and the Bengal commissions[7]. Understanding the role of Cyril Radcliffe and his approach to the partition is integral to explaining the violence and chaos that ensued because of it. Cyril Radcliffe and Lord Mountbatten, emblematic of British colonial rule as they were, had vast powers over the shaping of the borders but they arguably did not take that responsibility as seriously as they should have.

Historians agree that the nature and timeline of the boundary commission led to many issues in the Partition Plan and by extension, in the creation of India and Pakistan. While Cyril Radcliffe worked with a commission of Hindus and Muslims from India, the decisions ultimately fell to him. As a white, Christian, English-speaking, British man who hadn’t been east of Paris, Radcliffe had almost no local knowledge in Indian affairs or history. The main source of information under which he based his final report was census data that outlined provinces based on their religious breakdown. The logic was that Muslim majority provinces went to the newly independent Pakistan and Hindu majority provinces went to ‘Hindustan’ (i.e., India).[8] In theory, this made sense, but two issues made it extremely complicated – the census data used was outdated and some provinces barely had a religious majority, meaning that they still contained large populations of other religions. In spite of that, Radcliffe still used that data and took a demarcation approach based on a simple majority of each province. The lack of local knowledge isn’t just an indictment of Radcliffe himself, but rather reflects the manner in which the British had conducted themselves over the 190 yearlong period of colonial rule – with disregard of the local population and making no real attempt to understand the varying cultural, religious and ethnic divides for any purpose other than exploitation. An exploration of British India’s history would lead one to see that identities were not simply Hindu, Muslim and Sikh. In the contested regions of Punjab and Bengal, the Muslim-Hindu divide was not easily observable but rather depended on a history of tribal agreements, rural-urban divides and other social factors. For example, in Punjab in 1941, although Muslims enjoyed a 53.2% majority over the 29.1% Hindu and 14.9% Sikh populations[9]; the actual composition differed in the east versus the west and in urban areas versus rural villages. [10] Muslims held a majority in the west and non-Muslims were a majority in the east and, on a microcosmic level, urban centres in Punjab contained higher shares of Hindu populations due to higher literacy rates, access to urban employment and service industries. On the other hand, Muslims dominated rural areas, which made their majority harder to define. If the Commission were to just award Muslim areas to Pakistan and Hindu areas to India, Punjab would be a collection of enclaves and virtually impossible to divide. This is not to excuse Radcliffe’s decision but rather to demonstrate the lack of effort to understand these local complexities and, instead, push forward with sweeping assumptions about Punjab and Bengal. The consequence of awarding, say, a province to Pakistan with a simple Muslim majority was that it created an arbitrary division between Muslims and non-Muslims in that province and as a result gave rise to nationalism, religious revivalism and radicalism. In addition to that, the partition would essentially divide up the Sikh community in Punjab; surprisingly, Lord Mountbatten knew this and approved the plan anyway.[11] The ‘Radcliffe Line’ ignored the obvious consequences that would occur because of its divisions and in that regard made Britain’s final legacy in India one of perpetual ignorance and miscalculation.

Another major failure of Radcliffe’s partition plan was its secrecy and actual implementation. The first mistake of the British colonial state was preponing the date to implement partition from the original date of June 1948 to August 1947 – nearly 10 months ahead of schedule.[12] As I noted earlier, Lord Mountbatten valued expediency over precision during this time and so this decision was an example of his behavior. Mountbatten masked his extreme expedience as some sort of goodwill to the Indian people while, in reality, his real motivation was to protect the reputation of the British colonial government and deflect any responsibility from the lawlessness that would ensue. The operation of dividing British India into two new states was not just the creation of the border but involved the division of the British Indian Army, the civil services and bureaucracy. It was a heavily consequential and unrealistic decision by Mountbatten to expect this operation to conclude in just a few weeks when the building of those institutions took the British a few decades. Characterized with disinterest, Mountbatten approached partition with little appreciation for the scale of the plan and even less empathy for the Indian people who would live with the chaos of an expedited plan. Perhaps the most glaring example of this lack of empathy was when Nehru sent Mountbatten a letter expressing concern over the violence that was already occurring in Lahore, and Mountbatten met with Nehru shortly after, not to discuss the violence but, his ideas for a new Indian flag.[13]

As a consequence of Mountbatten’s expediency, Radcliffe had just between June 30th and August 14th to demarcate the border between India and Pakistan. The secrecy of the boundary Commissions became a major issue; most famously, the use of “other factors” to determine whether provinces went to India or Pakistan made many regions heavily contested.[14] ‘Other factors’ could be anything that Radcliffe, Mountbatten or the Commission considered relevant to the demarcation. This left so much room to consider geographic, cultural or historical factors to which Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs alike had a claim. Following partition, the Commission’s plan was effectively undermined by the clause which left so many regions contested by Hindus in Pakistan and Muslims in India, particularly in Punjab. Nationalists on either side of the border could bolster their territorial claims beyond the Partition Plan even more confidently because of the other factor’s clause. This is not to say that Radcliffe’s Commission had an easy job by any measure, but the inclusion of this criterion proved to be more problematic than helpful in the long run. Furthermore, the migration that was already under way as a result of the violence did not find a place in Radcliffe’s Commission, thereby making the awarding of contested provinces detrimental to their future residents.[15] Overall, the final equation for partition was incomplete: due to outdated census data, migration patterns, the ‘other factors’ clause and the shortened timeline. All together, these factors were catastrophic once Independence Day reached. Bizarrely, the actual partition plan wouldn’t be made public until two days after India and three days after Pakistan gained independence. In the days and months that followed, millions upended their lives and moved to a different country while many others did not survive. The violence, lawlessness and chaos that ensued was the logical conclusion of Mountbatten’s expediency, Radcliffe’s flawed Commission and a lack of local safeguards.

Anywhere between 200,000 and 2,000,000 people died in the period of partition, 100,000 women were abducted during that same period and millions displaced.[16] In the ensuing months, nine million people fled to Punjab alone and Bengal would witness the largest migration during partition – all in all, the Partition Plan led to the greatest migration of peoples in the 20th century.[17] It is hard to imagine that this was the result that Radcliffe wanted, let alone Nehru or Jinnah. The human cost of this partition plan is perhaps the defining legacy of British colonialism. Evidence of ethnic cleansing, mass rapes and brutal murders would be engrained in the national consciousness of both India and Pakistan and, undoubtedly, became the perspective by which each nation came to see each other. During this period of violence, while extremists and fanatics were emboldened, national institutions were enhancing religious animosity. For example, courts and judges often sided with their own religious communities in cases that involved “partition rioters” and acquittals were very common for members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a right-wing Hindu nationalist paramilitary group.[18] When assessing the claim that British colonialism left behind benefits, one must consider their entire legacy that they left behind including partition. The same railways that the British built, transported trains full of dead bodies into Pakistan; the same rule of law they introduced was ignored in favour of religious tribalism; and the same radio system that they brought was used to broadcast hateful propaganda against Muslims and Hindus alike.

The case of Kashmir is a particularly unique one – it encapsulates the hurdles of partition as a whole with an added layer of complexity. Kashmir, located in the West of Punjab, was of strategic and economic interest to both India and Pakistan.[19] The Radcliffe Commission on Punjab clashed particularly over this issue and “other factors” were certainly a main point of contention. Kashmir’s uniqueness is its governance structure – it was one of the princely states with which the British maintained a relationship of indirect rule. Kashmir’s ruler was a Hindu Maharaja governing over a largely Muslim population and, under the Indian Independence Act, he chose to remain independent and not join either dominion until the period of paramountcy ended.[20] The Commission awarded parts of the region to Pakistan and India – most notably, the allocation of the Muslim-majority region of Gurdaspur to India was significant as it violated the very basis upon which the Radcliffe Commission demarcated the borders. [21] Pakistan made efforts to annex Jammu and Kashmir shortly thereafter and, with that, began an unending era of Indo-Pakistani conflict over the region. At its core, the case of Kashmir shows the ineptitude of Radcliffe’s partition plan and the Indian Independence Act. Had there not been an option for princely states to remain independent and, instead, be awarded based on religious composition and geographical contingency, the case of Kashmir may have been more easily resolved. The extent of the British legacy over Kashmir didn’t end with Independence but extended into 1948 while Lord Mountbatten was still Governor-General of India.[22] Lord Mountbatten oversaw the ascension of Kashmir to the Dominion of India in 1948 and his personal relationship with Nehru is thought to have colored his perspective on the dispute. Now, over 70 years on, the Jammu and Kashmir dispute are one of the longest-running territorial disputes in the world and has led to multiple wars, continuous border aggression and an expensive show of force in both India and Pakistan.[23] This is compounded by the fact that both nations are now nuclear powers and the threat to both themselves and the international community is profound. In this hasty evaluation of the dispute over Kashmir, it is clear that the disinterest and recklessness of the British colonial government has had far-reaching consequences that are being lived throughout India and Pakistan and, surely, for the citizens of Jammu and Kashmir.

When the U.K. Parliament voted to pass the Indian Independence Act, they effectively abandoned their responsibility to any and all Indians on the subcontinent. This is abundantly clear in the political, social and economic ramifications that followed the Partition Plan of 1947. Many of Britain’s positive colonial legacies were used not for the betterment of the subcontinent as a whole but abused and exploited for political gain and expedience. Reflecting on Radcliffe’s plan and the reasons for its failures, it becomes clear that only under one kind of environment could it have succeeded – one in which the Punjabi and Bengali identity was removed entirely and, in its place, a Pakistani identity was created overnight. Radcliffe’s plan required a type of religious and cultural uniformity that simply did not exist in the Indian subcontinent. The issue of identity should be discussed in relation not only to language or religion but to territory as well. As nationalist movements grew in India and Pakistan, the disputes that they discussed often related to territorial claims, as was the case in Jammu and Kashmir. Nationalism was certainly not a product of the Partition Plan, but the type of arbitrary identity that Radcliffe attempted to enforce created a space for some nationalists to project fearmongering, extremist views and incite violence against the other groups. Notably, the violence that ensued during partition became engrained in the national consciousness of the subcontinent and consequentially became a part of the national identity. In essence, partition and its consequences created identities that may not have otherwise existed – these identities of grievance and violence continue to influence national politics in both countries and their relationship. For instance, the Bharatiya Janata Party, a political party founded on Hindu nationalism, believes in a kind of territorial and religious nationalism that has its roots in the partition process. Their ideological foundation can help explain Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to revoke Kashmir’s special status in 2019 and the BJP’s 2019 Citizenship (Amendment) Act in 2019, which was the first overtly religion-based discriminatory law in India’s history.[24] This is just one example where the Partition Plan has endangered Indians and Pakistanis today – in Kashmir violence continues and in India anti-Muslim violence is on the rise. There are a multitude of ways in which Britain’s colonial legacy has continued to present obstacles to governance in India and Pakistan, from Kashmir to Gujarat to Punjab and beyond, due to issues not discussed in this essay. Nuclear arms situated on both sides of the border further complicates the challenges to governance and undermines any argument for positive British colonial legacies.

British apologists who look to the introduction of the rule of law, English education or even tea as evidence of a good colonial legacy stop looking after 1947. The plunder and exploitation that occurred during British colonial rule continued after their departure; and, although the British did not start it, they instead used it for their own economic and political gain. A series of reckless and misguided decisions in the final year of British colonial rule dictated the path that India and Pakistan would take as independent nations. Lord Mountbatten made a series of decisions, both willingly and unwillingly, that fanned the flames of division between India and Pakistan. Sir Cyril Radcliffe did not cause the British’s problems, but he concluded them in an equally problematic way that was consistent with British colonialism – with no regard for the Indian people and with the sole purpose of protecting the British Raj. But maybe the best indictment of Radcliffe’s plan came from Radcliffe himself who, after submitting the plan to Lord Mountbatten, left India fearing that the Muslims and Hindus would try to kill him.[25] In the end, Radcliffe left, Mountbatten left, Britain left, and the Indians and Pakistanis were given a subcontinent they hardly recognized – one that is rife with divisions, built on violence and driven by oppression.

Mostafa El Sharkawi is a student pursuing an Honours Bachelor of Arts at the University of Toronto with majors in International Relations and Public Policy. His research interests focus on the politics of the Right in South Asia, democratization in the Middle East and humanitarian policy.

Bibliography

Bhaumik, Saurav. “The Radcliffe Award Grant of Gurdaspur: An Elemental Key to the Indian Strategy in Kashmir” History and Sociology of South Asia. (SAGE Publications, 2015): 20-35, https://doi.org/10.1177/2230807514546800.

Bose, Sugata, and Jalal, Ayesha. “Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy.” Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2004.

Khan, Yasmin. “The Great Partition.” London: Yale University Press, 2007.

Krishan, Gopal. “Demography of the Punjab (1849-1947).” Journal of Punjab Studies. Santa Barbara: University of California, Santa Barbara, 2004.

Rashid, Muhammad, Mohammad Ali bin Haniffa and Nor Azlah Sham BT Rambely.“Radcliff’s Award: An Ethical Imbalancement”. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 21, no. 3 (Kuala Lumpur: University Utara Malaysia, 2018).

Slater, Joanna. “Why protestors are erupting over India’s new citizenship law” The Washington Post, December 19, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/why-indias-citizenship-law-is-so-contentious/2019/12/17/35d75996-2042-11ea-b034-de7dc2b5199b_story.html.

Talbot, Ian. “Partition of India: The Human Dimension”. Cultural and Social History 6, no.4 (Southampton: The University of Southampton, 2009), 403-410, 10.2752/147800409X466254.

Wolpert, Stanley. “Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India.” Cary: Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 2006.

[1] Yasmine Khan, The Great Partition (London: Yale University Press, 2007.), 3.

[2] Stanley Wolpert, Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India (Cary: Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 2006), 134.

[3] Wolpert, Shameful Flight, 135.

[4] Wolpert, Shameful Flight, 135.

[5] Khan, The Great Partition, 122.

[6] Muhammad Rashid, Mohammad Ali bin Haniffa and Nor Azlah Sham BT Rambely.“Radcliff’s Award: An Ethical Imbalancement”. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 21, no.3 (Kuala Lumpur: University Utara Malaysia, 2018): 2.

[7] Rashid, bin Haniffa and BT Rambely, “Radcliffe’s Award”, 2.

[8] Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal. Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy. (Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2004.), 150.

[9] Krishan, Gopal. “Demography of the Punjab (1849-1947).” Journal of Punjab Studies. (Santa Barbara: University of California, Santa Barbara, 2004): 83.

[10] Krishan, Gopal. “Demography of the Punjab (1849-1947).” Journal of Punjab Studies. (Santa Barbara: University of California, Santa Barbara, 2004): 83.

[11] Wolpert, Shameful Flight, 154.

[12] Khan, The Great Partition, 3.

[13] Wolpert, Shameful Flight, 160.

[14] Khan, The Great Partition, 105.

[15] Khan, The Great Partition, 105.

[16]Ian Talbot. “Partition of India: The Human Dimension”. Cultural and Social History 6, no.4 (Southampton: The University of Southampton, 2009): 405.

[17] Talbot, “Partition of India”, 404.

[18] Khan, The Great Partition, 137.

[19] Saurav Bhaumik. “The Radcliffe Award Grant of Gurdaspur: An Elemental Key to the Indian Strategy in Kashmir” History and Sociology of South Asia. (SAGE Publications, 2015): 21.

[20] Bose and Jalal, Modern South Asia, 157.

[21] Bhaumik, “The Radcliffe Award Grant of Gurdaspur”, 21.

[22] Wolpert, Shameful Flight, 170.

[23] Bhaumik, “The Radcliffe Award Grant of Gurdaspur”, 35.

[24] Joanna Slater, “Why protestors are erupting over India’s new citizenship law” The Washington Post, December 19, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/why-indias-citizenship-law-is-so-contentious/2019/12/17/35d75996-2042-11ea-b034-de7dc2b5199b_story.html.

[25]Wolpert, Shameful Flight, 157.