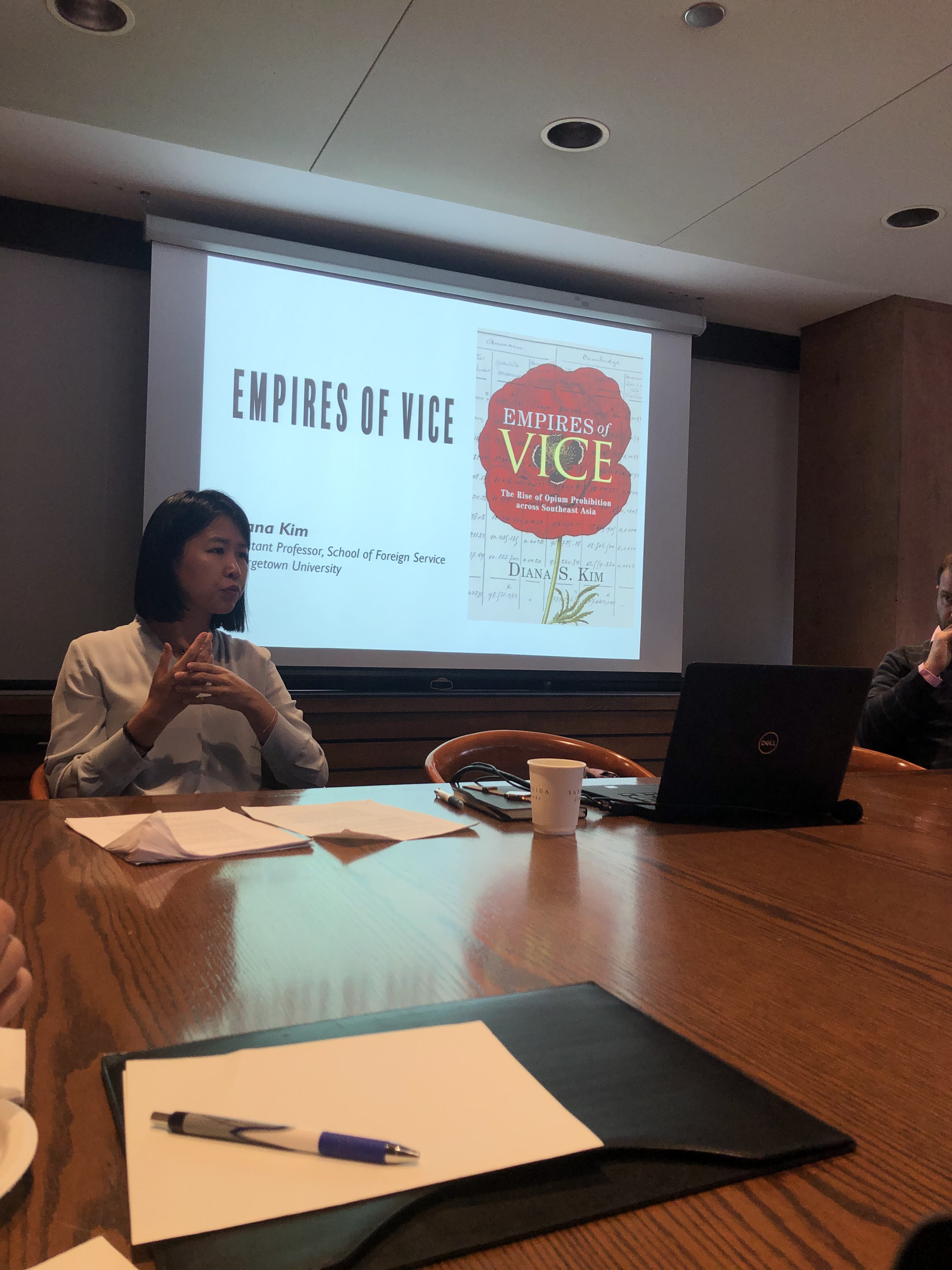

On February 26, the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies hosted Dr. Diana Kim, Assistant Professor at the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. This was the first public talk since her book, “Empires of Vice: The Rise of Opium Prohibition Across Southeast Asia,” was published fresh off the press only a week before. Dr. Matthew Walton opened the event on behalf of the Centre with a land acknowledgement, tying Dr. Kim’s work on historical colonialisms to the settler colonialisms of today.

Dr. Kim described her work as an exploration of the “inner life of the bureaucratic state told through opium,” claiming that the rise of opium prohibition is often overlooked and misunderstood. This phenomenon, she argued, is especially seen in Southeast Asia – a region dense with countries that continue to enforce the death penalty for drug-related crimes. Her main research question was derived from the shift in European colonial narratives from the 19th century to the first half of the 20th century. Whereas opium was initially defended as crucial to colonial governance in terms of taxation and maintenance of fiscal power, it later became an illicit substance unanimously disavowed by these countries and was institutionally condemned in the 1936 Geneva Trafficking Convention. From this, Dr. Kim argued that the local administration which previously taxed and regulated opium flows were uniquely armed with discretionary power to turn the tide from fiscal dependency to prohibition.

To reconstruct the genealogies of the opium monopolies (régis) of Southeast Asia, Dr. Kim performed twenty-two months of archival research spanning across temporal periods and spatial repositories. This included Cambodia, France, Myanmar, Vietnam, the United Kingdom, and the United States and ranged from the 1890s to the 1940s. She discovered that while these opium regimes may seem similar from first glance, the internal operations and administrative challenges recorded in daily reports are specific to the region.

Burma (now Myanmar) was highlighted as a case study where local administrative processes have put in place a nation-wide ban of opium since 1894. This made it the first of colonial states to do so —even before the international conventions in 1909 and 1912 – despite its fiscal dependency on the taxation of the substance. She said that twenty years of Burma’s bureaucratic records show a link between petty theft and opium consumption, with the substance being blamed for causing “moral wreckage”. Dr. Kim located the first instance of logged opium misuse to Akyab Jail in 1874. She traced the moral life of opium in these records with marked cases of opium related deaths and illness. These cases accumulated in the standard practice of collecting inmate statistics of opium use and fatalities by 1877. This practice of opium user observation was then expanded to towns and eventually moved upward to the national administrative body, provoking anxieties about the effects of the substance in generating a disorderly, crime-riddled, and “morally wrecked” population by the 1890s.

Dr. Kim pointed to colonial administrator Donald Mackenzie Smeaton as the proponent of opium prohibition by calculating Burma’s suspected demographic portion of drug users through collected reports of opium deaths (amounting to 11% of the population). She explained that the label “morally wrecked” was also Smeaton’s handiwork— a term which then spread to European colonial bureaucratic rhetoric in discussions concerning opium. She stated that Smeaton was a strong proponent of the claim that the use of the substance causes crime and pushed for the opium ban which was already in consideration by 1892 and enacted in 1894.

The lecture concluded with the proposition by Dr. Kim that the state is more vulnerable and prone to collective influence than it is assumed. She maintained that the everyday practices of administrators, who forge the work of the state from the inside, can even inspire a change in international moral consciousness. She emphasized that, due to financial dependency on the substance, prohibition was especially difficult for the Southeast Asian region and that these contemporary post-colonial states are essentially built upon the reserves of opium revenues. It is in this context that Dr. Kim stressed the adoption of an anti-drug stance in the 1950s as a mechanism used to delegitimise political rivals and to renounce a nation’s own involvement in the commercial opium trade. Such findings can reveal insights into why the region has some of the harshest drug penalties in the world today.

Kana Minju Bak is a third-year student majoring in Contemporary Asian Studies and Diaspora and Transnational Studies. She is an Event Reporter for Synergy: The Journal of Contemporary Asian Studies, Southeast Asia section. Her major academic interests include Asian diasporic experiences, Southeast Asian migrant labour policies and practices, and political relations in the Asia-Pacific region.