On February 12th, 2019, the Centre for Southeast Asia Studies hosted an academic seminar with Professor Alicia Turner, entitled “Colonial Secularism, Buddhism and the Continuing Violence of Burmese Women’s ‘Freedom’.” The event took place in the Natalie Zemon Conference Room, located at Sidney Smith Hall at the University of Toronto, St George campus. The event was chaired by Professor Nhung Tran, the Director of the Centre of Southeast Asian Studies. Professor Tran opened the event by thanking the University of Toronto’s Department of History for co-hosting this seminar. Professor Alicia Turner is an Associate Professor of Humanities and Religious Studies at York University. Professor Turner’s presentation was developed from the fifth chapter of her current book project, which studies the intersections of gender and colonial secularism and a genealogy of religious difference in 19th-century Burma.

Professor Turner began her contribution to the “conversation at home” by noting that her talk and current projects do not study contemporary Burma. Rather, her work is one that studies colonial history in the context of her framework as a religious historian. Her study of gender and colonial secularism in 19th-century Burma stems from questions about how difference becomes engrained in a society, and what precisely constitutes the concepts of religion, religious tolerance, and gender equality.

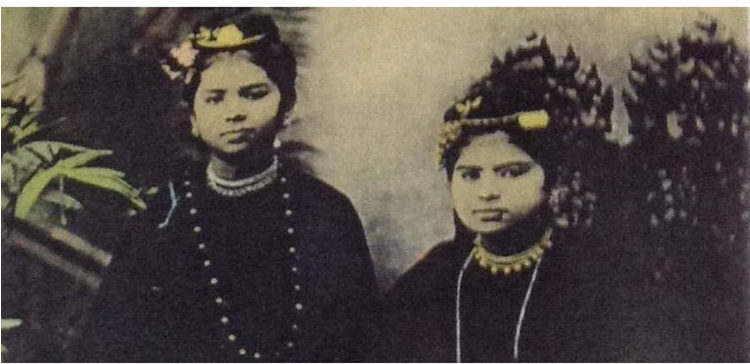

Starting with the regulation of interreligious marriage, perceived as a threat to Burmese demographics, Professor Turner identified the interrelation between two myths: the image of the predatory and seductive Muslim men who marry Buddhist women, and the notion that the Burmese nation must protect its women. Both myths are bound in the ancient and engrained narrative that Burmese women have more freedom and autonomy than other Southeast Asian women, and even more freedom and rights than Western women. This narrative is repeatedly found in the textual archives of 19th-century Burma, written by European scholars and travelers. These texts express a keenly European shock and delight about the so-called freedoms of women in Burma, in contrast to their “oppressed” counterparts in China and India. Thus, the question is – what constitutes freedom, and what evidence exists to support this long-held belief?

Professor Turner further provides her insights on the basis of the excellent scholarship of Chie Ikeya, notably her book “Refiguring Women, Colonialism and Modernity in Burma.” Also referencing authors such as James Low (1831) and Charles Forbes (1878), Professor Turner teases out and complicates the idea of “freedom.” European writers and scholars point to the presence of Burmese women in business and in the economy, and their relatively easy path to a divorce if so desired. Forbes in particular notes that in these freedoms available to Burmese women, some were even rights that English suffrage were still advocating for. This external perception and definition of freedom contributed to the widening gap between perceptions of Burma and India, which subsequently complicated the purpose of colonial intervention. If Burmese women were already free, and indeed freer than their English counterparts, the narrative of British colonialism as an intervention to grant women the rights that their “savage customs” withheld began to fall flat. Both British colonialism and English suffrage used the so-called suffering of colonized women to further their own political agendas. Burmese women, with their access to divorce, ability to own property, right to occupy economic or commercial roles, receive and give inheritance, and hold child custody, all poked holes in the intertwined narratives presented by colonial authorities and European authors. Thus, in the archive of writing on Burmese women, their freedoms were cemented as “accomplished facts.”

The question, again, is what constitutes this freedom? In her talk, Professor Turner shared an exercise that she uses in her undergraduate classes. Using the evidence at hand, can we identify what is valued by this society? In this case, if Burmese women can own property and hold child custody, what does Burmese society value? Through this exercise, Professor Turner illuminates what is missing when one only examines the “rights” of Burmese women – the role of Burmese men. Burmese society values male monasticism. Thus, in a society where a large portion of the male population are monastics and do not have roles in the domains of business and child-rearing, women must take on these roles. If monasticism is valued, then the ‘freedoms’ Burmese women enjoy in fact place them at a lower stature in Burmese society. Freedom does not have one universal definition.

Professor Turner then looked to the 1890s, when Buddhism was constructed as a new world religion, and the aforementioned freedoms enjoyed by Burmese women were labelled as an essential tenet of Buddhism. This strategy of colonial secularism, namely attempts to separate nation and religion into the public and private spheres respectively, was employed effectively to create Buddhist law and Muslim law, which replaced Burmese law and respectively governed their now separate people. In the private sphere, religion and gender became intertwined. Professor Turner works with Saba Mahmood’s concept of “pernicious symbiosis” and Talal Asad’s analysis of the colonial construction of religion as a category, which argues that religion is fundamentally distinct from every other facet of identity. Professor Turner first argues that the constitution and regulation of religion – in this case, as Buddhist and Muslim, rather than as Burmese – are key techniques of governance. This conceptual re-ordering of religion under family law, rather than national law, is how concepts of religious identity and difference became engrained under the narrative of secular neutrality. Thus, by 1865, religious identity as a Buddhist or a Muslim was necessary for one to be legally legible and intelligible. Religion had become an “unbreachable barrier.”

Professor Turner broadened her scope to look at the “discovery” of Buddhism in European thought and writing in the late 19th century. Buddhism became the first “new” faith with the potential to become a world religion, resembling the manner of Christianity, but it could not do so without a founder or leader. In this search, European authors found a figure for revolutionary reform in the Buddha. Buddhism, now a textual object, became the deliverer of liberation, rather than Burmese culture. Safely tucked away in the private sphere and confined to religious identity, Buddhism did not pose the same threat to the colonial project, in comparison to the idea that Burmese culture was more “enlightened” than British values. Thus, intermarriage became the threat to the implementation of colonial rule. Intermarriage made colonial subjects who changed their religious identity legally illegible, and also produced new Muslim subjects rather than Buddhists, thus constituting a demographic threat. Knowing already the “accomplished fact” that Buddhist (rather than Burmese) women had more freedom than their Muslim Burmese counterparts, it was difficult to comprehend and “legally inconceivable” why a Buddhist woman would reduce her “freedoms” by marrying a Muslim man and becoming Muslim herself. Turning back to Mahmood’s concept of “pernicious symbiosis” (2015), Professor Turner outlined the ways in which secularism enmeshed gender and religion in the private sphere. According to Mahmood’s analysis, this enmeshing is a “novel arrangement” (2015). In this religious historical framework, Professor Turner concludes that Burmese women are trapped by their own “freedoms”.

During the discussion period that followed her presentation, Professor Turner drew a laugh as she pointed out her concerns about Burmese men in the contemporary political sphere, who subscribe to the narratives portraying Muslim men as seductive and irresistible in the eyes of Buddhist women. Professor Turner drew another laugh when she expressed her disappointment in the lack of complexity in the Ma Ba Tha’s ideology as a contemporary Buddhist nationalist association, a subject that arose in the Q&A period. Although the census is a modern technology, Professor Turner noted that the freedoms of Christian Burmese women were never perceived as a demographic threat in the same way that Buddhist-Muslim intermarriage was, thus occupying less space in relevant discourses.

Sebastin Noor is an event reporter for the SouthEast Asia section of Synergy Journal.