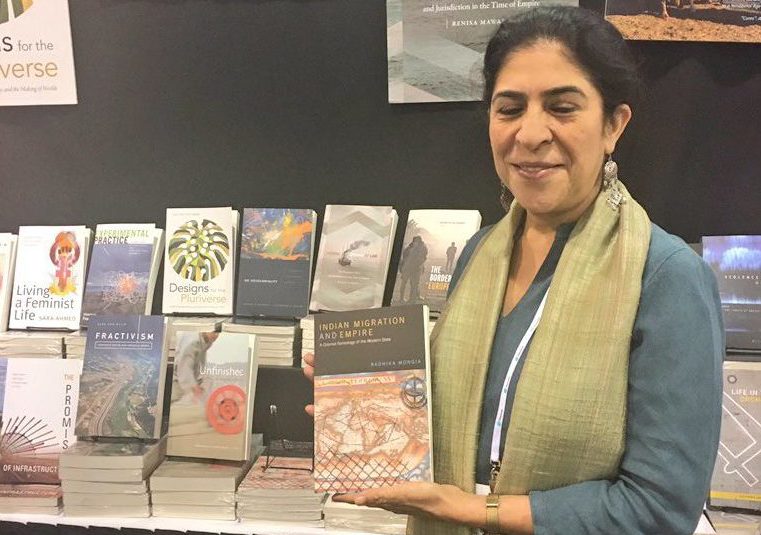

On Friday September 28th, 2018, Professor Radhika Mongia presented at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. This event was titled “A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State”, and it was sponsored by the Centre for South Asian Studies and co-sponsored by the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies. The speaker, Professor Radhika Mongia, is an Associate Professor of Sociology at York University. Her talk drew upon ideas in her recent book “Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State”.

Professor Mongia began by stating her main argument both in the book and in the forthcoming talk. She argues that, historically, the state has not always held a monopoly over migration. Professor Mongia proceeded to highlight the co-production of the modern state and the colonial state. Until rather recently, the conceptual framework treated the metropolis and the colony as two distinct and unrelated entities. However, attention to their intertwined relationship reveals “how the rationales employed in the regulation of colonial migrations are embedded in normative understandings of the modern state and how they inform, animate, and, often, are amplified in current migration regimes”.

Historical inquiry into the 19th century reveals how the British abolition of slavery in 1834 fostered anxiety over the “freedom” of migrants recruited to replace slave labor. The historical circumstances produced by abolition justified the intervention of the state in regulating the movement of Indian indentured migration to ex-slave plantation colonies. Since, at that time, ideas of state sovereignty did not include control over migration, state intervention was deemed an exceptional measure, based on “humanitarian concerns”, and was “a radical departure from past practice”. In prior cases, such exercise of state authority would have been regarded as a violation of the liberty of the subject.

According to Professor Mongia, the notion of state sovereignty as including control over migration occurred only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Her presentation analysed the legal debates surrounding Indian migration to Canada in the early 20th century. At the heart of these debates were the racial dimensions underpinning the anxiety surrounding migration flow of Indians into Canada. At first, Canada’s proposals aimed to curtail migration from India by imposing monetary requirements and mandating the issuance of passports. These attempts failed due to the lack of cooperation by the Indian government to enact policy and legislative changes proposed by Canada. Moreover, Canada itself failed to implement measures that effectively stopped the migrant inflow. Then, in 1913, Canada imposed conditions such as the ‘continuous journey’ criteria, which meant that all immigrants must arrive in Canada directly from “their country of birth or citizenship.” This was not possible for migrants from India, since such a route of direct ship transit did not exist at the time. As a result, the ‘continuous journey’ requirement was quite successful in preventing Indian migrants from arriving in Canada. However, everything would change with the arrival of the Komagata Maru in 1914 that, according to Professor Mongia, led to legislative changes in both India and Canada.

Earlier principles that granted British subjects the right to move and settle in any part of the Empire were now being reconfigured under a new understanding of state sovereignty. This reflects the intertwined relationship Professor Mongia spoke of at the beginning of her talk, where the colonial state and the modern state emerged not as distinct entities, but rather as inseparable from one another. Thus, colonial relations took a center stage in the emergence of the nation-state’s monopoly over migration, transforming understandings of what sovereignty entailed. State sovereignty in the 19th century contrasts with that of the 20th century: in the 19th century state intervention in migration control was an exception; in the 20th century it became the norm. Therefore, migration control and measures such as the criminalization of movement without a passport from British India, were linked to the defense of white Canada.

This historical inquiry, further elaborated in Professor Mongia’s book, highlights the limitations of analytical frameworks that contrast the colonial state with the modern state. Professor Mongia’s approach incorporates the co-production of colonial and modern statehood, which illuminates not only historical trajectories that led to the emergence of modern states, but also the process by which territorial borders are produced.

Professor Radhika Mongia concluded her talk by calling upon the audience to rethink the distinction between the modern and colonial state. She urges us to re-conceptualize this dynamic as a co-constitutive relation.

Anna Aksenovich is an event reporter for Synergy: The Journal of Contemporary Asian Studies, South Asia section.