Abstract

Kerala is a southern state in India known for its impressive social development. While absolute deprivation has been eliminated for the vast majority of the population, lower castes continue to experience social and economic inequality. In 2008, the Government of Kerala launched the Centre for Research and Education for Social Transformation (CREST), which aims to improve the employability and social mobility of lower caste youth. The school focuses on teaching proper self-presentation and communication in order to provide students with the “soft skills” needed to navigate a competitive job market. This paper draws on ethnographic fieldwork conducted at CREST over the course of seven weeks in the summer of 2017. The paper explores how caste is manifested in the lives of the students and at the school as a phenomenon which is simultaneously present, hidden, and denied. I examine how social and cultural capital structure experiences with caste, as well as how caste is hidden through the invisibility of social and cultural capital and through “passing”. I also problematize CREST’s approach of addressing inequality through targeted strategies of self-improvement and argue that this pedagogy contributes to the denial of caste by staff members.

Keywords: Kerala, caste, social capital, cultural capital, inequality

Introduction

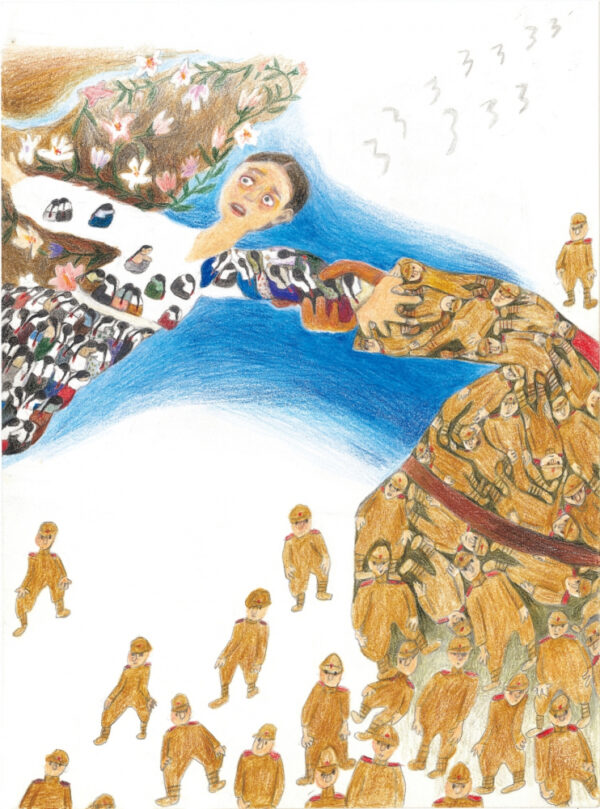

It was morning session at the Centre for Research and Education for Social Transformation (CREST) in Calicut, Kerala. The courtyard buzzed with the sound of 30-odd postgraduate students talking animatedly in small groups. All hailing from academic backgrounds in the sciences, the students were trying something a bit different today. Saima had given them 30 minutes to put together short plays to present to the class.[1] The topic could be anything, so long as the students exhibited creativity and comfort playing a role in front of the class. As we all settled back into our seats after the allotted time, the first group got into character and prepared to begin their skit. Students laughed watching their classmates fumble with props and talked amongst themselves, but when the acting began, the room fell quiet. The play recounted the story of an alcoholic man who beats his wife and kids. The wife pleads her husband to stop drinking, but each day he goes out with his friend and comes back drunk. In the evenings, the children look on from the next room, where they try to do their homework alone while listening to their parents argue. One day, the husband’s friend overdoses and dies. The husband, traumatized by what he has witnessed, comes home and pledges to never drink again. The play concludes with a happy ending.

The play was met with thunderous applause from the class. Saima commended the students for telling a story with such an important message. “Alcoholism is a big problem in many tribal communities”, she says. After class in the halls, many students come up to Ajit, the student who played the role of the husband, and congratulated him for his emotional and convincing performance. One of the other students who was in the play explained proudly that Ajit came up with the concept himself. Everyone was very impressed. At the end of the day, Ajit and I sat on the steps outside the school and spoke privately. I echoed the enthusiasm expressed by others for his talent. “You wrote the play about your family, didn’t you?” I enquired. Ajit nodded and said, “yes”. “I like the ending” I said. He smiled.

CREST is an autonomous institution launched by the government of Kerala in 2008 to improve the employability and social mobility of Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST), and other marginalized groups. The institution runs a variety of programs that help students “gain confidence, build competence and achieve excellence in all spheres of human endeavour for their social, cultural, and economic development”.[2] Over the course of seven weeks in July and August of 2017, I had the opportunity to intern at CREST in its Post Graduate Certificate Course for Professional Development (PGCCPD) while doing ethnographic research through the Anthropology Department at the University of Toronto.

I open with the story above because of its usefulness in illustrating several themes that emerged during my time at CREST, also to be discussed throughout this paper. The aforementioned play may be viewed as a snapshot of the circumstances familiar to some (though not all) of the students who come to CREST. The alcoholism depicted in the play is a result of many intersecting factors such as economic deprivation, social exclusion, caste discrimination, and lack of access to education and good-paying jobs. Conditions at home also have ramifications for children who must go through school with little to no assistance from their parents, while studying in a poor learning environment.

The play was also the most explicit discussion of caste inequality I observed during my time at CREST. While CREST works with lower-caste students its programming, direct discussion of caste is almost non-existent. Instead, CREST follows a deliberately individualized curriculum, promoting personal self-improvement over discussion of systemic casteism. The teachers at CREST seek to provide underprivileged students them with the “soft skills” needed to succeed in a competitive job market. The exercises of writing and play performance in English are one small piece of a broader curriculum intended to improve English proficiency, communication skills, confidence, and self-presentation. Thus, the play is symbolic of what CREST is seeking to transform.

The play also revealed an interesting puzzle. Ajit, the student playing the lead role, chose to keep his tribal status a secret from his peers at CREST. It is not surprising that a tribal student outside the institution would harbor shame over one’s identity, but this presents an issue in the context of CREST. While Ajit has achieved many of the markers of social and cultural development that CREST seeks to cultivate in its students, he continues to lack the confidence needed to embrace his own tribal identity, even within a school intended to build confidence in SC/ST students. Throughout the discussion that follows, I will return to these issues and depict the varying ways in which caste is present and absent in the lives of the students and in the institution. I focus in particular on three dimensions of caste: caste as present, caste as hidden, and caste as denied. First, some background on Kerala and theories of social and cultural capital is warranted.

Beyond the “Kerala Model”: Theories of Social and Cultural Capital

Kerala is a southern state in India known for its impressive social development, greatly exceeding other parts of the country. The state of Kerala has drawn interest among social scientists for its relatively low Gross Domestic Product yet simultaneous significant human development marked by near universal literacy, low infant and mother mortality, and life expectancy far beyond that of any other state in India.[3][4] Commonly known as the “Kerala model”, this success has been linked to the state’s unique political history of elected Communist leadership and its extension of public services.[5] While absolute deprivation has been eliminated among the vast majority of the population, vulnerable groups in Kerala continue to experience social and economic inequality. In particular, SC/ST populations experience disproportionate poverty and lower educational achievement.[6] This disparity is tied to colonial processes of land dispossession, and has been further intensified through neoliberal policies of privatization.[7]

Bourdieu’s seminal piece “The Forms of Capital” offers a useful theoretical framework with which to discuss persistent inequality in Kerala. Bourdieu expands the traditional notion of economic capital to argue that capital, and by extension power, also exists in social and cultural form. Social capital refers to the networks from which an individual can draw, and one’s membership in particular groups. Cultural capital is further divided into three forms: embodied, objectified, and institutionalized. Embodied cultural capital refers to “long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body”, such as mannerisms, conversational style, and other seemingly automatic characteristics of thought and behaviour cultivated over time, otherwise known as habitus.[8] Objectified cultural capital refers to “cultural goods” such as books, musical instruments, or clothing, which exemplify status. Lastly, institutionalized cultural capital generally refers to educational qualifications as well.

Caste as Present: Tribal Identify and Forms of Capital

Within the SC/ST category, there is significant diversity among the experiences of CREST students with economic, social, and cultural capital, as evident through my interactions. While some students from wealthier family backgrounds did not view caste as a dominant feature structuring their lives, others described numerous experiences of both caste-based discrimination and lack of opportunity. Ajit is a useful example worth discussing in detail.

Ajit is ST, falling into the minority among the mostly SC cohort at CREST. He is from the district of Wayanad, known for its dense forests and high tribal population. His parents have a limited primary education and work in agriculture. Ajit and his siblings grew up poor. While he was going through primary school, there was no electricity at home and often not enough money for a nutritious diet, owing to the poor wages his father earned working on a plantation. Furthermore, his father was an alcoholic and would often beat his mother and siblings. While some wealthier families choose to put their children in private English medium schools for primary education, Ajit went to a public school where English was not taught. Once in high school, however, English became mandatory in all subjects. Ajit struggled to keep up with many of his classmates. Ajit recounted instances of humiliation by teachers who chastised him for his “poor learning”. Moreover, Ajit dreaded writing his surname (which contains his colony name) on documents and receiving the government stipend for SC/ST students, because these processes unfolded as a public display that made his tribal identity visible, often resulting in ridicule from his peers at school. In fifth standard, Ajit joined a program in Wayanad aimed at empowering tribal students in school. Ajit credits the resources and guidance he received there for helping him pursue higher education. Ajit explained that his situation improved significantly once in college, because he was living in a hostel rather than at home, with access to college resources such as computers and libraries. Moreover, he was better equipped to present himself socially because he was “more balanced emotionally”, better-dressed, and more proficient academically and in English communication than had been the case during his years in primary school. Still, Ajit noted to me that him and his tribal student peers were “not much brilliant” compared to their “brilliant” upper-caste classmates.

Bourdieu’s insights on forms of capital can explain some of the disparities Ajit experienced. In the case of education, Bourdieu’s argument articulates the existing intersections between all three forms of capital. The lack of economic capital in Ajit’s family resulted in a poor learning environment at home and may have also contributed to his father’s alcoholism. The tight economic situation also meant that Ajit’s parents did not have the time to help him with school work. Thus, the limited economic capital of his parents resulted in their inability to cultivate institutionalized cultural capital in the form of educational qualifications for Ajit. Even if Ajit’s parents had time to assist him, their own limited primary school education made them ill-equipped for this task. Ajit has elder siblings who may have been better suited to this, but their own obligations towards their parents meant they were often too busy helping with agricultural work to mentor or encourage Ajit. The lack of economic capital in Ajit’s family also lowered the affordability of English medium school. This multitude of factors resulted in Ajit’s lack of access to cultural capital, placing him at a disadvantage when he entered his English-speaking high school. While more privileged students benefited from a conversion of economic and cultural capital through investment in private education, Ajit’s lack of one form of capital blocked access to another. This also had repercussions in the realm of social capital, as Ajit’s situation resulted in ridicule at school by both teachers and his peers, separating him from the social network of upper-caste students.

The program Ajit joined in Wayanad helped fill some of these voids, and granted him new opportunities to access and cultivate forms of capital. Ajit explained that the program gave him access to computers and libraries, resources not otherwise available due to his family’s lack of economic capital. The centre also gave students opportunities to practice “mingling”, thus helping tribal youth develop a form of embodied cultural capital that more privileged youth might gain through their families’ social networks. The program staff members themselves also had knowledge pertaining to academics, college admissions, and proper etiquette that others within Ajit’s immediate social network lacked. Thus, the connections Ajit made with the program staff broadened his social network to include those who had social and cultural capital. As Bourdieu notes, the volume of social capital held by an individual depends on both the size of the network of connections (which Ajit was able to expand), as well as “the volume of the capital (economic, cultural, or symbolic) possessed in his own right by each of those to whom he is connected”.[9]

Ajit also explained that the staff at this program were instrumental in his application and acceptance to college. This comment reflects the notion of “capacity to aspire” coined by Appadurai (2004) and closely related to Bourdieu’s discussion on capital. Appadurai describes the “capacity to aspire” as a navigational capacity, which “thrives and survives on practice, repetition, exploration, conjecture, and refutation.”[10] One dimension of this capacity is the access of privileged youth to the experiences and lessons of their parents. Upper-caste parents with college diplomas, for instance, are able to guide their children through the process of applying to college. They are also more capable of recognizing and cultivating the prerequisite actions and qualities required to gain admission. While Ajit’s parents’ lack of social, cultural, and economic capital meant that they were not in a position to offer Ajit this navigational guidance for his college applications, the staff at the Wayanad program were. The program also served to disrupt what Smith (2011) calls a “transgenerational family script”. Coming from a family where nobody held a post-secondary degree, the default plan for Ajit’s personal journey did not include going to college. The program he participated in helped interrupt and redirect this “script”.

While the Wayanad program was hugely beneficial for Ajit, it did not entirely erase the impacts of his lower-caste background. As Ajit explained, it was evident in college that the tribal students were not as “brilliant” as the upper-caste students. The abilities of upper-caste students are the result of their previous and current access to various forms of capital. As Bourdieu notes, “ability or talent is itself the product of an investment of time and cultural capital”.[11] Ajit’s family did not have the time (as a result of limited economic capital) nor the cultural capital to invest in him to the extent that upper-caste families often do, resulting in Ajit and other tribal students appearing and even feeling intrinsically less “brilliant” in college.

A secondary form of caste-discrimination emerges from efforts aimed at addressing discrimination. As noted above, Ajit was often ridiculed by classmates for receiving the government stipend given to SC/ST students. The stipend served as a marker of his tribal identity, making him an easy target. It also did not help that students at Ajit’s school were called up to the front of the class to receive the stipend, making a spectacle out of something that could have otherwise been done privately. Thus, the stipend, as well as the method of its distribution, makes SC/ST identities visible, potentially reinforcing negative stereotypes of laziness and deficiency attached to this demographic. As Shah and Shneiderman (2013) note, in the eyes of upper-castes, reservations may be seen as unfair or viewed as rewarding typical lower-caste deficiencies. Indeed, this sentiment was expressed by one of the teachers at CREST, who claimed that the students only want government jobs because it is an easy route to a good salary and little work. He elaborated on this to me privately, explaining that the students are accustomed to being handed things to them through reservation, resulting in their tendency to want “rights but no duties”. The teacher couched his criticism in the language of reservations, but inherently, he was reiterating tropes of lower-castes being both lazy and undeserving.

Caste as Hidden: Invisible Chains of Capital and Passing

Thus far, I have outlined ways in which intersecting forms of capital can create deprivation that falls along caste lines. For Ajit, the presence of caste was visible through his experiences of poverty, discrimination, and lack of opportunity. There are other cases, however, where caste is not as visible. Sometimes, caste may be either deliberately hidden as an identity marker, or its presence as an agentive social structure can be obscured. I will discuss the latter first as it is tied to the preceding discussion on forms of capital.

Economic capital is the most visible form of capital. For students like Ajit where economic capital was lacking, it was easy to observe and describe processes of inequality. Other students at CREST, however, had ample economic capital but still lacked capital in other realms. When asking these students about their experiences with caste, the most common response was that they were not affected by it. Several students noted that their parents’ generation experienced caste discrimination and economic deprivation, giving examples of poor work conditions and low-wages as employees of upper-caste-owned plantations. They insisted, however, that because this was no longer the case, and caste did not apply to them. Such comments ignore how the experiences of their parents have implications on their own generation.

The same students that denied the relevance of caste also noted that the most important factors in their employment prospects are personal connections and self-presentation. One student explained that with good connections, one can get a job without writing the prerequisite exam required for most jobs. She explained that on several occasions where she had interviewed for a position and did not get the job, she later found out it went to someone who had not written the exam. Access to “connections” is no accident. It is a form of social capital accumulated over time and across generations. Parents of upper-caste students who were not working on plantations in the previous generation were developing important connections in government and corporate sectors, which later helped their children bypass steps in a competitive job market – such as writing an exam. Moreover, “self-presentation” is not an innate quality, but rather a form of cultural capital. It is taught and cultivated by parents and others in an individual’s immediate social network. Good mannerisms, conversational style, etiquette, and knowledge of appropriate interview protocol are all qualities that upper-caste students are more likely to possess due to greater cultural and social capital. The impacts of caste emerging from a lack of social and cultural capital may be difficult to observe, because they are often manifested as a lack of advantage, rather than as explicit negative discrimination or poverty. Thus, lower-caste students at CREST who claim caste does not affect them may have not experienced the same overt discrimination as Ajit, but these students are still affected by the inaccessibility of opportunities presented through good “connections” or “self-presentation”.

Another hidden dimension of caste is the deliberate obscuring of markers of lower-caste identity, otherwise known as passing. Erving Goffman’s discussion on stigma and social identity in his book Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, Goffman distinguishes virtual social identity from actual social identity. The former refers to the character imputed on an individual based on assumptions about the category to which he or she belongs, and the latter refers to the attributes possessed in reality. Stigma is the special discrepancy between these two types of identities, an attribute that is “deeply discrediting”.[12] In some cases, the discrepancy between virtual and actual social identity is immediately apparent. For example, an individual with a missing limb or a physical disability is in most situations clearly identifiable. This person is thus already “discredited”, and their task in social situations is to manage the subsequent tensions that inevitably arise. In other cases, the differentness of the individual is not immediately apparent. This person is not discredited but rather “discreditable”, and may live in fear of being “found”. Thus, such individuals do not manage existing tensions, but rather manage the “undisclosed discrediting information” that could make their social stigma apparent.[13] It is this managing of information that, when successful, can result in the discreditable individual “passing” as normal.

This latter case of management is what may occur in the case of caste as social stigma. A low-caste person in a high-standing social position (for example, being a top student or having a good job) embodies a tension between virtual and actual identity. The virtual identity of being high-caste is the assumed attribute of anyone in a reputable position, while one’s actual identity may be of a low-caste. Ajit has often found himself in this situation. By the time he was in college, Ajit was a top student, now having obtained two master’s degrees and intending to pursue a PhD. He is also fairly light-skinned, making his tribal identity less obvious based on appearance. Given these characteristics, Ajit has discovered that it is possible for him to pass as upper-caste, or at least not tribal, sometimes even without much deliberate effort on his part. For example, Ajit explained that when he was growing up, he was sometimes mistaken as not from a tribal background, simply because of his skin colour. Once, he was invited into the home of an upper-caste person who did not realize Ajit’s tribal identity. Later, when the upper-caste lady discovered his tribal demographic marker, Ajit was not re-invited and was instead treated poorly in further interactions. This situation is described by Goffman as “unintended passing”, a prerequisite experience that prompts the stigmatized individual to learn to “pass” deliberately, (hopefully) not being quickly discovered of one’s identity, as was the case in Ajit’s unintended passing. This example also points to the importance of (in)visibility in passing. In the case of Ajit’s skin colour, this attribute helps make his stigma less immediately visible.

In high school and college, Ajit began making deliberate efforts to pass. Part of this process involves hiding what Goffman calls “stigma symbols”, referring to signs that “[draw] attention to a debasing identity discrepancy, fragmenting what would otherwise be a coherent overall picture”.[14] One symbol of stigma clearly associated with tribal individuals is having red-stained teeth from the habitual chewing of a plant found in Wayanad. Ajit was able to easily eliminate this symbol from his identity and further aid the process of passing. Another sign that helps an individual pass is a “disidentifier”. This refers to a sign that tends to “break up an otherwise coherent picture but in this case in a positive direction desired by the actor, not so much establishing a new claim as throwing severe doubt on the validity of the virtual one”.[15] In Ajit’s case, his ability to speak English, a quality he began improving upon through the program in Wayanad and even more so at CREST, serves as a useful disidentifier.

Passing is not always easily achieved, and can also create negative experiences for the individual who passes. Documented identity, for example, is much harder to hide. As Goffman notes, “biography attached to documented identity can place clear limitations on the way in which an individual can elect to present himself”.[16] This is the problem Ajit encountered when he wrote his surname on forms. Another possible side effect of passing is ambivalence towards the group of stigmatized individuals to which the passing individual belongs. As Goffman outlines:

[T]he stigmatized individual may exhibit identity ambivalence when he obtains a close sight of his own kind behaving in a stereotyped way, flamboyantly or pitifully acting out the negative attributes imputed to them. This sight may repel him, since after all he supports the norms of the wider society, but his social and psychological identification with these offenders holds him to what repels him, transforming repulsion into shame, and then transforming ashamedness itself into something of which he is ashamed. In brief, he can neither embrace his group nor let it go.[17]

Ajit exhibited identity ambivalence when describing his own community to me. He lamented the fact that many follow what he considers to be primitive spiritual practices. He also expressed annoyance that tribal people speak a variety of different traditional languages, rather than simply adopting Malayalam. Throughout the discussion, Ajit conveyed his embarrassment and shame over tribal traditions that he felt were characteristic of “bad culture”, the same attributes for which he was shamed himself. Instead of disparaging the ways in which upper-castes inflict shame, he disparaged the shamed characteristics themselves.

Ajit has learned methods to help him pass in social situations involving upper-castes, but he also chose to do this at CREST. At the school, although all students are from lower castes, an inter-caste hierarchy between SC/ST students persist. Ajit was very aware of this dynamic, even if it has never manifested itself (to my knowledge) as discrimination between the students. It is troubling that an institution dedicated to increasing the confidence of lower-castes and facilitating their social mobility has not managed to imbue enough confidence in Ajit to stop concealing his tribal identity within the school. Goffman notes that it is not uncommon for stigmatized individuals who have learned to pass to subsequently feel that they are above passing and embrace their identity wholeheartedly. It may be overly optimistic to expect five months at CREST to help a student like Ajit unlearn years of concealment and exhibit a complete transformation. However, the institution can serve an important role in instigating such processes. Instead, CREST engages in an odd denial of caste. I suggest that this is tied to CREST’s deliberate approach of tackling caste inequality solely through targeted and individualized processes of self-improvement. This pedagogy as a form of denying caste-based differences is discussed below.

Caste as Denied: Curriculum and Students

CREST shares its campus with another government organization, the Kerala Institute for Research Training and Development Studies of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (KIRTADS). On the premises, KIRTADS runs a small museum with tribal tools, artifacts, and models on display. The main museum is inside a building adjacent to CREST, but some models are on display outside. The museum had not been discussed by anyone I spoke to at CREST. When I asked one of the staff members about it, his response was to immediately explain emphatically that the museum is casteist and that I should not go inside. He did not elaborate on how or why this is the case, merely stating that the existence of such a museum is in itself casteist. Later that day, I was interviewing Ajit and asked him for his opinion on the museum. Based on the staff member’s comment, I was expecting him to find the museum offensive. To my surprise, he was not offended by it at all. Instead, my question prompted him to start telling me about tribal huts in his colony that were similar to the models on display. This was a rare moment when he seemed proud talking about his tribal identity. I did not end up entering the museum, but I still found the discrepancy in reactions between the staff member and Ajit my question to be telling.

In her discussion of a similar institution for lower-caste students in Kerala, Lukose (2006) explains how caste is deflected or flattened in an effort to promote an environment of equality. My interaction with the staff member about the adjacent museum points to a similar situation at CREST. Throughout its curriculum, CREST highlights the importance of personal dedication, resourcefulness, and hard work. Students are taught that with enough effort, anything is possible. What students are not taught is how caste inequality is actively produced and reified in society. They are also not taught to be critical of the underlying conditions that enable one’s attendance at a school like CREST, or the requirements of becoming polished while others appear to simply possess these traits, recalling the “brilliant” upper-caste students described by Ajit. The path to equality outlined by CREST is essentially a denial of caste-related issues.

The denial of caste was made more explicit in a conversation with a “Personality Development” teacher at CREST. When asking her about a lesson on proper table etiquette and interview protocol, she became defensive to my questions, quickly noting that it is not casteist to teach this. She went on to say that she would teach any student these skills, as everyone in Kerala lacks practice with Western mannerisms such as handshakes and cutlery. When I asked her how she had acquired these skills, she explained matter-of-factly that her situation was different, having gone to a prestigious college in Mumbai and grown up surrounded by people familiar with proper etiquette. Thus, the teacher’s default assertion of equality reflects a discrepancy with her own experience, in which she herself benefited from access to resources not afforded to her lower-caste students. Returning to the example of the aforementioned museum, a similar “flattening” of caste helps explain the staff member’s response. For him, promoting caste equality was akin to denying caste differentiation. Thus, he found the tribal museum casteist simply because of the attention it draws to tribal difference.

The denial of caste by teachers at CREST also impacts the ways in which students conceptualize caste. Earlier, I noted that some students do not feel that caste personally affects them. This sentiment extends further, as some students expressed that caste is not only irrelevant to them, but to everyone in Kerala. In an online conversation, one of the students explained to me that “in the early times it [caste] was very crucial. But nowadays it is not a problem”. As a student about to complete a five-month course intended to address marginalization of lower-castes, it seems problematic to declare that caste is no longer a problem.

This issue is fundamentally tied to CREST’s pedagogical approach. The drawbacks of CREST’s pedagogy with regards to caste inequality are exacerbated when contrasted with the benefits of its unofficial approach to gender inequality. While the topic of caste is rarely explicitly noted by the teachers to the students, several female teachers did talk openly about gender equality and women’s oppression. It was also common for teachers to make explicit reference to how gender roles are taught and socially constructed. For example, one teacher told the story of Cinderella, but with the gender roles reversed. This unfolded into a discussion on how the stories to told young girls raise them to believe they need to be saved. The same teacher who denied the relevance of caste in her familiarity with table etiquette also frequently talked to the students about gender. On one occasion, she recounted an experience with a potential male boss who attempted to assault her. She was forthright in discussing the prevalence of gender-based violence and encouraged the students to think critically about how harmful views of women are reproduced in social interactions, giving rise to said violence.

The result of these discussions was positive. After the teacher recounted the story of Cinderella, some male students decided to rewrite a play they were creating in another class to give the female lead more agency. Moreover, at the end of my time in Kerala, many of the female students expressed to me how CREST has helped them see that women and girls can be strong. Deesha, a married student, told me with confidence how she intended to challenge her mother-in-law’s sexist views on the role of a wife. Her mother-in-law did not want her to leave the home if she managed to get a government job in another district, but Deesha explained that if she did get a job, she had every intention of working. “I don’t want to be just a housewife”, she said. While there are certainly many unresolved issues pertaining to gender, the critical discussions that unfolded on this topic pushed the conversation about gender forward, especially when compared to CREST’s approach to the issue of caste inequality. Many female students left CREST with a sense of pride for their identity as women and a renewed conviction in their abilities, but students like Ajit continued to harbor shame over his tribal identity.

There are a few factors that may have influenced the diverging approaches to gender and caste inequality at CREST. To start, the female teachers have a personal stake in the issue of gender inequality but not in caste inequality, as they are all upper-caste themselves. To my knowledge, the discussions that ensued on gender were not an official part of the CREST curriculum, rather something the female teachers chose to include themselves. They talked about gender because it affects them personally, thus making it not possible for them to deny its relevance. It is also possible that this divergence is reflective of and influenced by trends in broader state-sponsored and media discourse. Attention to gender equality is commonly perceived as a sign of development. It is also often evoked as a key feature of the praised Kerala model.[18] By contrast, caste is often construed in Western media as a marker of backwardness and underdevelopment, despite the presence of similar, though not institutionalized, hierarchical class and race structures in the West. CREST’s critical attention to gender but not caste follows these broader patterns.

I want to be explicit in stating that I am not arguing against a skills-based approach to overcoming inequality. Rather, I seek to draw attention to problems in an exclusively skill-based curriculum. As Delpit (1986) notes, minority students need to be taught skills in order to succeed in society, but this must be couched “within the context of critical and creative thinking” if it is to bring about meaningful and impactful change.[19]

A useful starting point in addressing this aspect of CREST’s educational approach might be to employ teachers who are themselves from lower-caste backgrounds. Their insights from lived experiences with caste inequality, as well as their ability to help infuse critical discussion on caste as the female teachers did in the case of gender, would be a positive addition to CREST’s pedagogy. Still, it is important not to place all responsibility of critiquing casteism on lower-caste staff. CREST as an institution must also find ways to critically examine systemic issues of casteism among its students, and work to resolve instances where casteism may be perpetuated by its own staff.

Conclusion

Caste presented itself in varying ways in the lives of the students at CREST, and in their experiences at the institution. For students like Ajit, caste was clearly manifested in experiences of poverty and lack of access to opportunities. Economic, social, and cultural capital intersect in lower-caste social positions to create situations of deprivation that subsequently reproduce themselves across generations. In other cases, where economic capital is ample, chains of social and cultural capital may be less apparent, making the effects of caste hidden. Caste may be also deliberately hidden for an individual to pass and avoid the humiliation and discrimination associated with a lower-caste identity. This is the approach that Ajit adopted both prior to coming to CREST and during the program. It is possible, however, for stigmatized individuals to eventually discard performative tactics of passing, and to undergo the more transformative and political journey of embracing one’s stigmatized identity. This is not a process encouraged or supported at CREST. While CREST certainly helps its students learn and implement “soft skills” that will aid them in navigating a competitive job market, the school does not encourage assessment of caste as a systemic and structural issue, an alternative approach that could lead to a more critical examination of power relations. There is promise, however, in the unofficial emergence of critical discussions on gender, spearheaded by female teachers at CREST. Applying a similar approach to caste would help CREST instill a deeper, more political understanding of inequality in its students. This process will help students enact more transformative changes in their personal identification and relationship to caste, and in their future impacts on society.

Works Cited

Appadurai, Arjun. “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition.” Culture and Public Action, edited by Vijayendra Rao and Michael Wlaton. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004, pp. 59-84.

Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Forms of Capital.” Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J Richardson. New York: Greenwood, 1986, pp. 83-95.

Centre for Research and Education for Social Transformation. About us, n.d. http://www.crest.ac.in/about.html.

Delpit, Lisa. “Skills and Other Dilemmas of a Progressive Black Educator.” Other people’s children: cultural conflict in the classroom. New York: The New Press, 1995, pp. 11-20.

Devika, J. “Egalitarian Developmentalism, Communist Mobilization, and the Question of Caste in Kerala State, India.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol 69, no 3, 2010, pp. 799-820.

Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. Prentice Hall, 1963.

Isac, Susamma. “Education and Socio-Cultural Reproduction: Development of Tribal People in Wayanad, Kerala.” Rajagiri Journal of Social Development, vol 3, no 1&2, 2011, pp. 1-30.

Jeffrey, Robin. “Legacies of Matriliny: The Place of Women and the ‘Kerala Model’.” Pacific Affairs, vol 77, no 4, 2004 pp. 647-664.

Lukose, Ritty. “Re(casting) the Secular: Religion and Education in Kerala, India.” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice, vol 50, no 3, 2006, pp. 33-60.

Mosse, David. “A Relational Approach to Durable Poverty, Inequality and Power.” Journal of Development Studies, vol 46, no 7, 2010, pp. 1156-1178.

Shah, Alpha & Shneiderman, Sara. “Introduction: Toward an anthropology of affirmative action.” vol 65, 2013, pp. 3-12.

Smith, Lisa. “Experiential ‘hot’ knowledge and its influence on low-SES students’ capacities to aspire to higher education.” Critical Studies in Education, vol 52, no 2, 2011, pp. 165-177.

Steur, Luisa. “Adivasi Mobilisation: ‘Identity’ versus ‘Class’ after the Kerala Model of Development?” Journal of South Asian Development, vol 4, no 1, 2009, pp. 25-44.

Endnotes

[1] All names are pseudonyms.

[2] N.d., Centre for Research and Education for Social Transformation (CREST). http://www.crest.ac.in/about.html.

[3] Devika, J. Egalitarian Developmentalism, Communist Mobilization, and the Question of Caste in Kerala State, India, 2010.

[4] Steur, Luisa. Adivasi Mobilisation: ‘Identity’ versus ‘Class’ after the Kerala Model of Development?, 2009.

[5] Devika, 2010.

[6] Isaac, Susamma. Education and Socio-Cultural Reproduction: Development of Tribal People in Wayanad, Kerala, 2011.

[7] Mosse, David. A Relational Approach to Durable Poverty, Inequality and Power, 2010.

[8] Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital, 1986. p.84

[9] Bourdieu. p.89

[10] Appadurai. Arjun. The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition, 2004. p.69

[11] Bourdieu. p.85

[12] Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, 1963. p.3

[13] Goffman. p.42

[14] Goffman. p.43-44

[15] Goffman. p.44

[16] Goffman. p.61

[17] Goffman. p.107-108

[18] Jeffrey, Robin. Legacies of Matriliny: The Place of Women and the ‘Kerala Model’, 2004.

[19] Delpit, Lisa. Skills and Other Dilemmas of a Progressive Black Educator, 1995. p.19

Amanda Harvey-Sánchez is a fourth-year student at the University of Toronto double majoring in Sociocultural Anthropology and Environmental Studies, with a minor in Equity Studies.