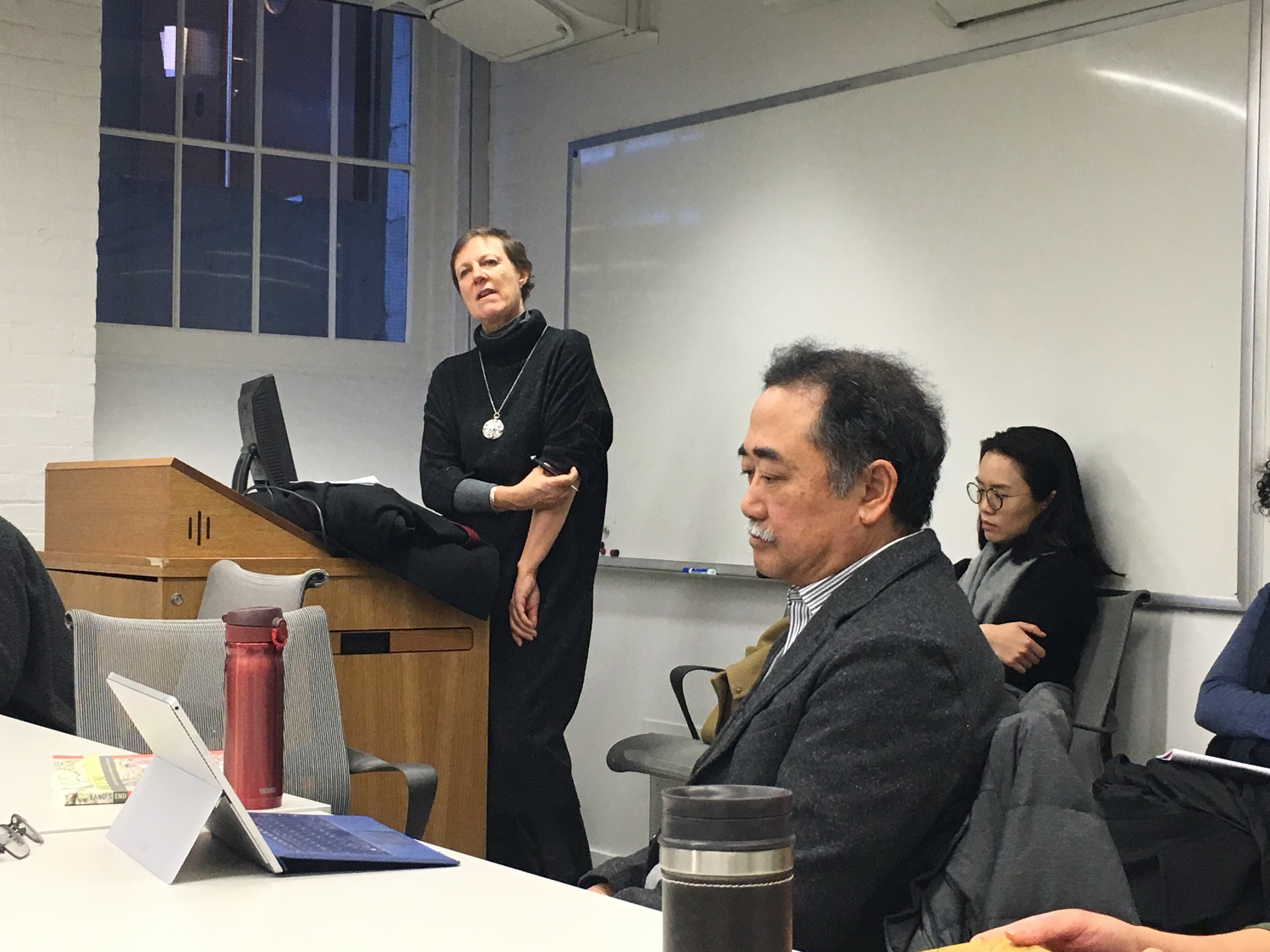

On January 26th 2018, the Munk School of Global Affairs hosted Professor Tania Li for a discussion on the concept and problem of indigeneity in Indonesia. The event was sponsored by the Dr. David Chu Program in Asia-Pacific Studies and co-sponsored by the Asian Institute and the Centre for Indigenous Studies. Professor Tania Li teaches Anthropology at the University of Toronto and is also the Director of the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, Canada Research Chair in the Political Economy and Culture of Asia, and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Her research focuses on indigeneity and land politics in Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and Asia. Some of her recent publications include Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier (2014) and Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia (2011). The event was chaired by the Director of the Dr. David Chu Program, Professor Takashi Fujitani.

Throughout the discussion, Professor Li challenged the concept of indigeneity and attempted to tackle this complicated case of land and social justice. In Indonesia, contentious discourses on the topic of indigeneity have taken place for decades. However, Professor Li argued, the concept of indigeneity forged within the framework of a “white settler’s model” is awkward and inappropriate in the South Asian context. The question of indigeneity defines identity on both a personal and political level. In Indonesia, however, it has never been sufficiently addressed. Unlike India or the Philippines, where contemporary concepts of indigeneity map neatly onto colonial categories used to distinguish peasants from tribes, the Dutch colonial power in Indonesia did not divide the population in the same way, making delineation especially problematic.

Furthermore, the stakes of determining who qualifies as indigenous in Indonesia have increased in the past decade. The idea of being indigenous has become attractive due to recent legislation recognizing the existence of distinct “customary communities” and allowing them to hold land communally. It is important to understand the passage of these land laws in the context of Indonesian history. During Sukarno’s presidency, 70% of the country’s land was seized by the government for “national development,” and was largely repurposed as cash-crop plantations. As a result, many land-owners and farmers were suddenly stripped of their livelihood and forced to become squatters. This abrupt land reform increased tensions, which have been aggravated recently as international donors and agencies have entered the picture. Their intention was to combat climate change and deforestation by advocating on behalf of indigenous groups, who they argue possess the “wisdom of treating the nature with care,” to reclaim the land. Land ownership has, therefore, become a critical issue in Indonesia, and indigenous people occupy the center of this political conflict.

The question of “who is indigenous” is extremely complicated, and there is no neat dichotomy between indigenous and nonindigenous. Professor Li proposed four criteria that could be used to define indigeneity – spatiality, linguistics, time of arrival, and cultural difference – but conceded that even they are too problematic to be the defining standards. Professor Li recognized that perhaps the best solution is to unite people rather than categorize them. The protection of indigeneity in Indonesia is undoubtedly important, but the question of “who was here first?” should not be the primary concern. She believed that the idea of “customary” law proposed by the Indonesian government could encourage a reversal of the hierarchical society introduced under the Dutch rule. The difficulty of defining indigeneity and the rising stakes of recognition in today’s Indonesian society present an undeniable challenge that must be addressed.

Ching-Lin Tiffany Kao is a third-year student studying International Relations and History at the University of Toronto. She currently serves as an Event Reporter for Synergy: The Journal of Contemporary Asian Studies, East Asian section. She is interested in cross-straits relations, including the socioeconomic situation and cultural similarities and differences in China and Taiwan.