I met Tenzin in Kathmandu, Nepal, on a research trip. He was born and raised in a remote village in Kham, a province that historically belongs to Tibet but divided into the Tibet Autonomous Region and Sichuan Province during the Chinese occupation in 1949. During the Cultural Revolution, as a child, Tenzin witnessed severe beatings of his parents. This experience led to his deep distrust towards the Chinese government. In pursuit of a better livelihood, he moved to Lhasa in the late 1970s. Although Lhasa was not developed back then, the government allowed Tibetans to conduct business. Tenzin made a fortune dealing antiques, but as he made more money, he felt increasingly unsafe. In addition to his experience during the Cultural Revolution, Tenzin also felt constantly targeted by Chinese government institutions and the police because of his ethnic identity. When he was in Lhasa, there were armies and police officers on the street everywhere to surveil Tibetans, but not the Han Chinese. He felt that events similar to the Cultural Revolution could easily happen again among Tibetans, and he would lose his life. This sense of insecurity and distrust led him to plan his escape.

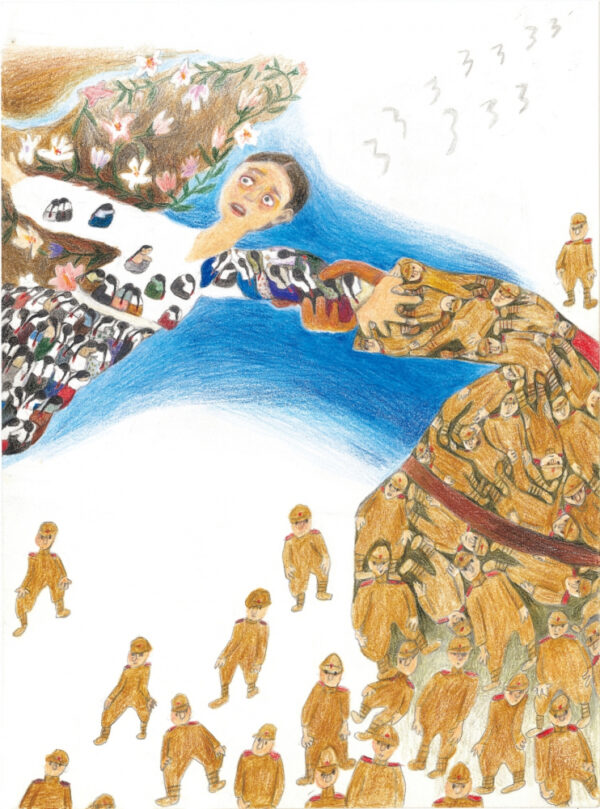

In 1984, Tenzin paid a professional guide to assist with his escape. He left with a few other Tibetans. First, they had to climb over the mountains at the border between Tibet and Nepal. To dodge the watchful eyes of Chinese border police, Tenzin had to sleep during the day by covering himself under black plastic bags and making his way towards Nepal at night. If discovered by police, he would have been shot instantly or sent to Chinse prison. Luckily, after half a month of arduous walking and starvation, Tenzin made it.

After he reached Nepal, Tenzin began a carpet business and reaped a profit in the 1990s, until India began to make Tibetan carpets at a low cost. He decided to close his carpet factory in 2004. In 2014, he returned to his village with his brothers on a Chinese visa. Tenzin recalled that he was given the visa because he did not engage in any political activity in Nepal, and the Chinese embassy/government is aware of this. During his trip, Tenzin saw the changes that took place in Tibet, particularly in his hometown. Before he left, there were no paved roads or lights. In 2014, this infrastructure was in place. Tenzin witnessed the significant improvement in the village situation, and in the quality of life for its residents. Despite this perception, Tenzin said that he would never choose to resettle in Tibet, because regardless of the economic development and opportunities in the region, he would never feel safe in a China-occupied Tibet. In Nepal, Tenzin felt as if he could do whatever he liked within the limits of the law. Furthermore, he believed that Nepal’s laws do not specifically target nor disadvantage Tibetans. He does not feel watched or restrained in Nepal. In China, however, he just doesn’t feel “free.” Life in Nepal is just as hard as it would be in China, but after all, Tenzin feels like a free man in Nepal, just like everybody else. In China, Tenzin feels like a second-class citizen, distrusted by the government.

Tenzin is just one of the many thousands of Tibetans who fled Tibet after 1959. In 1959, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama fled Tibet, 10 years after the Chinese Communist Party gained control over the region. The Dalai Lama’s flight was preceded by multiple failed negotiations between the central Chinese authority and the Tibetan administration, in addition to a Tibetan uprising on March 14, 1959. Thousands of Tibetans fled with the Dalai Lama to seek refuge in Dharamsala, India, via Nepal. This group was also designated political refugee status by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, known as the first wave of Tibetan refugees. Some made it to India, while others decided to settle in Nepal. According to Settlements of Hope: An Account of Tibetans Refugees in Nepal from the Cultural Survival Report published by the Dalai Lama’s Office, these refugees experienced many difficulties in Nepal, including the lack of international aid, hostility from the local Nepalese people, and a lack of response from the Nepalese government.

The Cultural Survival Report also indicates that most of the refugees who fled around 1960 experienced some form of persecution in China. Some fled after they had been captured by the Chinese government and sent to prison to be tortured or labour camps to be re-educated after the 1959 revolt. Others fled because they were found worshipping the Dalai Lama and were later tortured in prison for doing so. Their encounters with the Chinese government resulted in government interventions in their activities related to Tibet independence.

From 1959 to 1989, very few Tibetans fled China due to the tightened political atmosphere in China such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. From 1989 to 2008, the second wave of Tibetan refugee flight took place during China’s economic and political liberalization. According to Social Mobility and Change Among Tibet Refugees, there were 689 Tibetans who escaped in 1989, and this figure increased to 2066 in the following year. In 1991, this number reached 3374. The second wave of Tibetan refugee flight ended around 2008 as a result of the large-scale protests that took place in Tibet during the Beijing Olympic Games. The Chinese government sent troops into Tibet and arrested numerous Tibetans. After the crackdown, the government has since tightened border security by increasing the amount of patrolling. Furthermore, China has been building economic and political ties with Nepal in hopes that the Nepalese government will send Tibetan refugees back to the China.

The reasons why Tibetans flee their homes vary. Some leave due to political persecution, some leave to become monks and nuns in India due to the Chinese government’s restriction on the number of monastery personnel in Tibet, and others like Tenzin leave simply because they do not feel safe on their own land. The causes for departure are also highly complex, ranging from inconsiderate government policies to deep-rooted misunderstandings between Tibetans and the Chinese government. Nonetheless, Tenzin’s story is one reflection of the desperation felt by Tibetan refugees on their homeland and the difficult journey to escape.

The content of this article does not represent the positions, research methods, or opinions of the Synergy Editorial Committee. We are solely responsible for reviewing and editing submissions. Please address all scholarly concerns directly to the contributor(s) of the article.

The author of this op-ed has chosen to remain anonymous.