In 1980, Tibetan Lama Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok settled in an uninhabited valley called Larung Gar (“valley” in Tibetan) near Sertar County in Sichuan, China. A few of his disciples congregated around his hut to receive teachings. This is how one of the world’s largest and most influential Buddhist centres was born. Despite its modest origin, the Larung Gar Buddhist Academy grew rapidly over the course of the next three decades, both in size and in reputation. By 2000, there were around 10,000 monks, nuns, and disciples residing in Larung Gar.

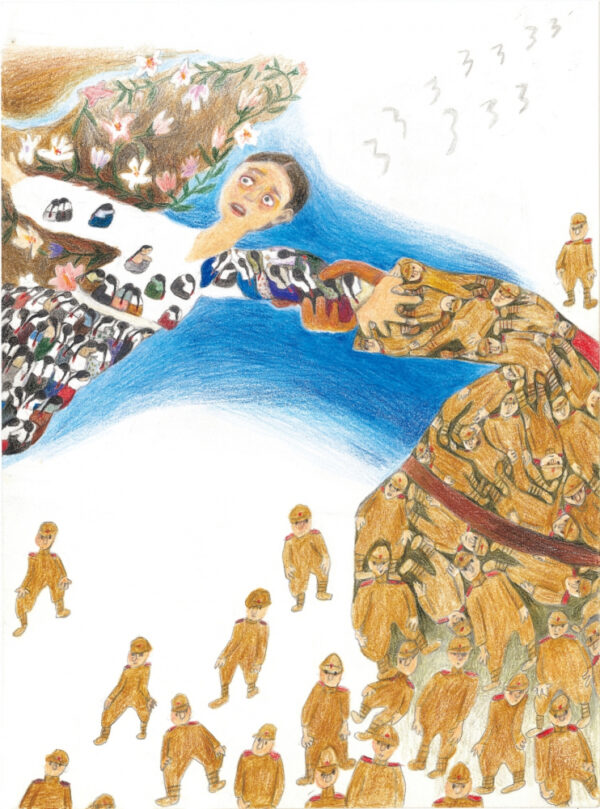

Although residents of Larung Lar focus only on the study and dissemination of Buddhist texts, the Chinese government sees more in them. In 2001, the local government demolished around 1,200 huts, and imposed as limitation on the number of residents in Larung Gar to 1,400 people. A Sichuan Religious Affairs Bureau official attributed this to “concerns about social stability … at the order of central authorities.” However, countering the wishes of the government, thousands of huts were rebuilt in the following years with help from local villagers. The Larung Gar Buddhist Academy continued to flourish.

Just when many observers thought that Larung Gar was either forgotten or ignored by Chinese local and central governments, a second wave of demolition began in July 2016. This time, the aim was still to reduce the number of huts and residents, but with a different reason. This time, local authorities cited their concern over Larung Gar’s overcrowding demographic, and expressed the need to half the number of residents. Why has the Chinese government, of both local and central level, been so focused on curbing the size of this seemingly apolitical Tibetan Buddhist center located in a random valley?

The most obvious reason is the fact that Chinese Communist Party (CCP) fears any form of large religious congregation. More precisely, the CCP knows the extent to which religion can influence individuals and how this influence could potentially be transformed into a threat to the stability of its regime. As an old Chinese saying goes: “once bitten by a snake, one shies at a coiled rope for the next ten years.” In the 1990s, the unrestrained expansion of the Falun Gong was perceived by the CCP as a highly political and threatening phenomenon that harboured the potential to instigate revolts against the government. Whether Falun Gong is indeed a religion and whether it did aim to threaten the CCP’s rule are still debated issues that fall beyond the scope of this article. The point is that the CCP thought it was both an evil religious cult and a scheme against the party. As a result, Falun Gong leaders were persecuted, practitioners were banned from practicing or imprisoned, and any mention of “Falun Gong” became taboo in China. While these tactics did successfully eradicate Falun Gong from China, it resulted in international backlash. Since then, the Falun Gong group has become another example for Western governments to use when they criticize China’s human rights record as pertaining to religious persecution. Unsurprisingly, the Chinese government does not enjoy being targeted with hard evidence.

Ever since the persecution of Falun Gong, the Chinese government has adopted a softer approach to restraining the influence of religious groups. It has set up religious bureaus in every level of government to regulate and discipline religious groups. Any religious congregation in China today must be pre-approved by its local religious bureau and be available for police inspection upon request. Church activities are only allowed to be held at government-designated locations, and boys can only become monks after reaching the age of 18. Regulations like these are very policy-centred and thus do not create much noise and cause explicit harm. They can rarely be used effectively as criticism against the Chinese government by interested parties. As a result, the Chinese government has been able to curb religious influence before it gets out of hand, like that of the Falun Gong.

This governing mentality may shed some light on the Chinese government’s persistent efforts at regulating the size of Larung Gar, but there may be another reason to account for the plight of Larung Gar. Buddhism entered Tibetan society during the eighth century. Since then, it has become the predominant religion of Tibetan people, thus affecting every aspect of their lives and minds. In fact, Tibet remained a theocratic state until 1950, when China gained sovereignty over Tibet. Since then, the Chinese state has encountered many difficulties in its attempts to control this ancient Buddhist land. In 1959, the fourteenth Dalai Lama, the religious leader of Tibet, went into exile accompanied by a large-scale uprising. From 1987 to 1989, protests and revolts were rampant in Tibet, and again in 2008.

The causes behind these historical events vary widely depending on the party one listens to. The Chinese government claims these events to be instigated by a few masterminds from abroad, whose aim is to destabilize the Chinese state. On the other hand, the Tibetan exile community maintains that the unstable situation is a sign of the people’s anger with the Chinese government for occupying their land and abusing their resources and people. The evaluation of these accounts is beyond the scope of this article, but the central takeaway is that the Chinese government views the Tibetan region as one filled with potentially destructive sentiments against the Chinese state. The government is fearful of Tibetans gathering in big crowds, not because their prayers, but because their prayers could turn into a blueprint for protest and the proliferation of one particular group’s religious influence. Buddhist values and ideals are irrelevant; the Chinese government’s belief that religion controls minds is what matters to the CCP. For these reasons, Larung Gar, one of the world’s biggest and most influential Buddhist academies, is not left unrestrained by the Chinese government.

While demolitions are still happening, with nuns and monks crying about their forced departure, this is in no way the demise of Larung Gar. On the contrary, just as what happened in 2001, more huts will be built to spread kindness and peace upon the debris of paranoia and distrust.

The content of this article does not represent the positions, research methods, or opinions of the Synergy Editorial Committee. We are solely responsible for reviewing and editing submissions. Please address all scholarly concerns directly to the contributor(s) of the article.

The author of this op-ed has chosen to remain anonymous.