Disclaimer: Please note that the views expressed below represent the opinions of the article’s author. The following work does not necessarily represent the views of the Synergy: Journal of Contemporary Asian Studies.

Note: the author is writing from the perspective of someone who has been raised as Chinese/Canadian and is mindful of the lack of South and Southeast Asian perspectives. Feel free to contact the author at thomas.siddall@hotmail.com to inquire about various anti-imperial perspectives across the Asia/s.

We cannot say we’ve escaped the violent images and imaginations of the white settler-colonial state. Our collective state of subjugation is designed around the continued reproduction of divisive categories based on their relativeness towards whiteness, and one of these categories is race. Lisa Lowe writes that “race as a mark of colonial difference is an enduring remnant of the processes through which the human is universalized and freed by liberal forms, while the peoples who created the conditions of possibility for that freedom are assimilated or forgotten.”[1] White power only functions when we are divided and forgetful. Asian/American/Canadian communities are subject to the process of political forgetting, and this takes the form of the model minority myth. The white, settler-colonial state relies on discriminatory racial logics, such as the model minority myth, that makes white life possible at the expense of full Asian life and especially at the perpetuation of the impossibility of Black and Indigenous life and labour. Kantian ethics and rules, which were focused on how to make decisions around right or wrong, supported a system of expansionist trade that oversaw imperialism through genealogy and language of racism. Trade empires of the 18th century saw their trade as part of the necessity to spread civilization and make “right” the apparently uncivilized states of Asia. Our rules are derived from white domination and racist structures, and there is absolutely no way to fix a system by trusting power holders alone to make change. Asian/Americans and Asian/Canadians have had a role in upholding Western genocidal imperialism, and we have got to do better in the fight to end imperialism. To do so, the global Asian anti-imperial archive has much to offer us in reversing our political forgetting.

The racist structures that makes Black and Indigenous life impossible are also the same ones that perpetuate the model minority myth and compel Asian/Americans/Canadians to claim the ignorance of whiteness. This manifests in statements such as “I didn’t know I couldn’t say the n-word because there weren’t any black people in Vancouver” (an actual statement I have witnessed someone make). In holding such views, the degree of personal and system-perpetuated forgetting is clear. Knowledge of events, events as recent as the 1970’s destruction of Hogan’s Valley,[2] a Vancouver community home to many Black families and businesses which was destroyed for a highway, is part of a more extensive system of political forgetting. Such erasure serves to reinforce the authority of the settler-colonial state. Though that highway was never built, the ritual forgetting of Black expulsion from Vancouver persists to this day in ignorance by our Asian/American/Canadian communities.

Asians in the United States and Canada are not free, are not “model minorities,” and are not independent of the settler-colonial system even though it appears that, colloquially, we came here after everyone else. Seeing Asians in the United States and Canada as intimately linked to their former homes and with their new ones highlights the dual political processes which are revealed in anti-imperial archives, and in this way we can break down racism in our communities.

There is a pervasive and deterministic belief that the abolition of slavery (if one were to believe that the 1865 U.S. abolition was a clean break) led to the incoming of indentured labour from China. This clarifies the subsequent implementation of the racist Chinese exclusion acts – which later expanded to ban all people from Asia. However, returning to Lowe, archival work illustrates how these forms of labour reproduction reveal the working of “political intimacy.” This means that in order to coordinate white imageries and fetishizations of labour productivity, white bodies came to be “possessive individuals”[3] over non-whites, forcing the latter into hierarchies in relation to whiteness. As such, Chinese labour became seen “as a solution to both the colonial need to suppress Black slave rebellion and the capitalist desire to expand production.”[4] Essentially, Chinese labour (the Chinese “coolie”) – which later expanded to Asian labour – became designated as a means to further expel Black lives in the United States and Canada.

It is too simplistic to say that the replacement of slave labour with indentured Asian labour was bound to happen. This could not have happened without a concerted effort by imperial governments to continue taking people from across the world with the goal of developing colonies for white businesses. In the Caribbean, for example, we see the formation of transnational European cartels to aid Portuguese commercial activity by importing East Indians to serve as both “a buffer population,” and as “the ideological rationalization of the allocation of that role.”[5] In both scenarios, a buffer population is created between white imperialists and Black people. Viewed in this light, the ban on Asian migrants was not about fear, but was a calculated move to maintain an equilibrium where Asians in the West could be dominated. At the same time, Western imperialists sustained a system of dispossession in Asia which subjugated Asian bodies and governments, including through maintaining a system of extraterritoriality and trade ports across East and Southeast Asia.

The exclusionary acts in Canada and the United States were replaced with new immigration laws in 1947 and 1952, respectively, as part of a shift in the global politics of immigration, nationalism, and capitalism due to World War II. Immigration laws, such as the Canadian Citizenship Law (1947) and the Immigration and Nationality Act (1952), were notable for their inclusion of national origin quotas, allowing once again for Asians to come to the United States and Canada – but often not by their own choice. The arrival of Asian migrants to the United States and Canada was, in part, driven by prolonged violence.

It was not evident during this time that anti-colonial activity in Asia would have led to the establishment of the nations we see today. In a continent desecrated by Western imperialism, to be alive was more clearly about the continuation of subjugation, but by a different master – the United States. The American empire did not force Asians to move to the American imperial core but incorporated systematized violence leftover from European and Japanese colonialism – such as the comfort women system which enabled the U.S. Army to sexually exploit likely hundreds of thousands of women. In fact, the catalyst for much of the nationalism in Asia was an outright rejection of the principles of the 1954 Geneva Conference, which was a continuation of Western border carving of North and South Vietnam, North and South Korea, Laos, and Cambodia. Asselin notes that the 1954 Geneva Conference was not about peace, but rather about the deprivation of the [Vietnamese] Communists of an imminent victory.”[6] Adding to this, we need to dispel the notion that the 1954 Geneva Conference was about bringing peace to Asian hot wars because the United States pushed France to continue its violent war throughout the conferences to give the United States an advantage in “negotiations.”[7] Border drawing was the impetus to sustain perpetual war by Western imperialism in Asia after World War II, which led to the mass exodus of many Vietnamese.

The carving of these borders in Asia accompanied shifting racial dynamics marked by a fear of Black liberation in the core of the American empire. Imperial whiteness sustained wars in Korea, Vietnam, and the occupation of Japan and Taiwan through the forced and unwanted conscription of poorer, and often Black, soldiers. These wars in Asia were not isolated, but an effect of the continuation of Western racist regimes. We as Asian/American/Canadians need to recognize that our presence in this land comes due to a lineage of imperialist history, which has also come at the cost of Black life.

The model minority myth also allows Asian/American/Canadians to participate in political forgetting by promoting education and opportunity as the reason we are here. This comes at the cost of the transnational networks of migration which were forged in trauma and pain because of the imperial occupation of Asia. One of such networks is the Korean-American adoption pipeline. This pipeline was formed by a complex of American military lawyers, evangelical Christian organizations, and the United States Congress, who lobbied and oversaw the passage of the Bill for Relief of Certain War Orphans (1955), a bill which allowed for more than two international adoptions per family. The rationale for this bill came about from concern over a lack of funding in South Korean orphanages, which dominantly housed the children of comfort women and American GIs, and the children of families who lost parents as a result of war.[8] Korean-born children arrived in the United States unable to speak English, having been severed from their kin, and being profiled and discriminated against by their community and adoptive parents.[9] This Korean story continues to this day and has expanded across Asia. To this day, while the Bill for Relief of Certain War Orphans (1955) remains small in scope, it has set a precedence that has overseen the expansion of adoption to across East and Southeast Asia. The bill’s repercussions made clear that Asian presence in the United States was possible only through tolerance. Today, the origins of the bill, which is rooted in imperialism and violence, need to inform our anti-racist activism.

Asians forced away from their homes and to America arrived in a landscape of shifting urban patterns and segregationist lines. Throughout the 1960s-1990s, urban segregation oversaw Black people’s forced kettling in urban centres without access to adequate labour, housing, or schooling.[10] This occurred in the backdrop of white flight due to overinvestment in suburbs.[11] Asians, both settled and new, took up the liminal space between Black and white in the new urban landscape of post-war American and Canadian cities. Open hostility to Asian existence as a result of Cold War conditioning also led to racism and discriminatory social norms. However, Asians in their new homes did not sit back lightly and accept these conditions. Rather, figures such as Yuri Kochiyama stood in solidarity with Black activists and comrades as part of the Civil Rights and Black Liberation movements.[12] Kochiyama was also an activist with the Asian American Movement, which advocated for Pan-Asianism and anti-War activity. This movement also brought up influential creators such as Theresa Hak-Kyung Cha and David Henry Hwang.

The fight for racial liberation was a transracial one, involving Asian activists like Kochiyama working with Black liberation activists like Malcolm X. Yet in the United States, the suppression of Black liberation necessitated the removal of Asian support, which is seen by the perpetuation of the model minority myth. It was a term first used by a 1966 New York Times article entitled, “Success story, Japanese–American style”, and it designated the success of Japanese/American communities as a result of family structure and cultural emphasis on hard work, no matter the language and cultural barriers.[13]

As Asian communities in the United States and Canada grew and became more established, it became possible to bring over family members like grandparents, who could stay at home and watch the children while parents were working. Due to the parallel practice of “home” and “family”, it appeared that Asians were a model minority. However, the model minority myth was a way to orient American and Canadian society to the new economic landscape based on financialization and wars in Asia. The myth actively locked Black people out of the economy through the denial of Black Americans to institutions of higher learning, preventing them from escaping the draft.[14] To claim to belong in the model minority myth is not only ignorant to the fact that Asians are not homogenous, but also makes Asians docile in an economic structure and culture that makes Black lives impossible at the expense of Asian/American/Canadian financial accumulation. The model minority myth still exists today, and it is used to reinforce the notion that racism can be overcome by hard work and strong family values. When we live in a society that actively stereotypes Black families as “broken,” we need to smash this racist trope. We need to be liberated from the model minority myth, and that begins with un/learning, and learning real solidarity.

Today, shifting urban patterns have seen the movement of Asian/American/Canadians to affluent suburbs, the gentrification of downtown cores, and the exile of Black and racialized peoples from affordable housing. Waters’ study of Chinese migrants in Vancouver notes the introduction of the 1986 investor category into the Canadian immigration system, which generated the arrival of numerous transnational Chinese families.[15] This underscores the fetishization of diverse Asian populations with wealth, which was co-opted to gentrify dense urban development and the skyrocketing cost of living/land in cities and suburbs. bell hooks, in Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance, says that whiteness in a multiracial society is about the “crises of identity in the west, especially as experienced by white youth,” which are “eased when the ‘primitive’ is recouped via a focus on diversity and pluralism which suggests the Other can provide life-sustaining alternatives.”[16] The gentrifications of downtowns and suburban Asian enclaves have been subject to a greater emphasis on urban renewal projects and on up-scaling diverse cuisines and services. This underscore whiteness in urban planning through pricing out and making inaccessible spaces for Black and racialized peoples. The perceived newness of racial diversity in gentrified urban cores and presence of international investors creates the “advantages of racial membership” in a multiethnic, multiracial society, which “are routinely capitalized for Whites.”[17] In a way, Asian “success” has been systematically designed to remove Black and racialized bodies from spaces dominated by whiteness – Asian “success” continues the designation of Asians as a divider between whiteness and Black bodies. Asian “success” is systematically in service of whiteness. To make this quite clear, the presence of Asian bodies and the perceived increased visibility of Asians in urban spaces is not the result of deemphasizing race in urban planning but is about co-opting capital gains via the fetishization of Asians for white urban development and segregation by new means.

Returning to Hogan’s Alley, the process of political forgetting has meant that we need to do better to actively think about our subjectivity within the racial logics of empire. We need to do better when it comes to dismantling racism. An article circulating on WeChat right now amongst Chinese American and Canadian communities disregards the Chinese translation of Black Lives Matter’s letter to educate our parents. The article states “你的父母们,也许没能得到更好的教育,但你有没有想过,他们来到美国,所承受的生活的重担,远远超过了你为之爱心泛滥的非裔” (Translation: “Your parents may not be able to get a better education, but have you ever thought that they came to the United States and the burden of life they bear is far more than that of the African-Americans for whom your love is rampant”). I read this article, and I did not know what to say; if you had received this type of strongly worded, culturally coded message, how would you respond? George Orwell, although validly criticized today for his complacency in anti-communism, wrote about the implications of imperialism over 90 years, stating that “if Burma derives some incidental benefit from the English, she must pay dearly for it,” indicating that British imperialism was despotism with theft as its final object.[18] For us Asians, we may believe that we have gained from moving to the West, but to gain the “benefits” of imperialism, we are also subject to white imaginations of Asian bodies and forced to forget the crimes of Western empire. Racism and imperialism are co-constructed, and for many of our families, imperialism – in the form of “education” and “opportunity” – are the reason we are here today. It is the reason nearly all of us in Canada and the United States are here, and we need to reconcile that our presence is the result of Indigenous genocide and anti-black violence.

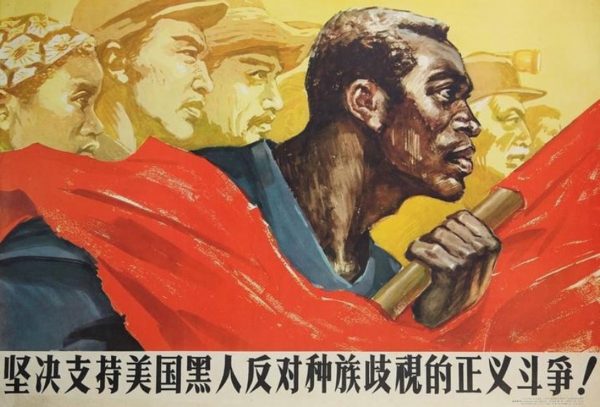

Educating our communities is not just about anti-Black racism, although that is extremely important, it is also about Black and Asian liberation. The statement “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” does not come out of a vacuum. Just as Black liberationists have been active and here to teach us their stories, Asian/American/Canadians need to join with them. Asian anti-imperialism has a long history that we might find to be a useful and revealing archive to teach our families. The 1960s Civil Rights and Black Liberation movements were not without international support, and much of it was coming from the recently liberated nations of Asia. American imperialism, which brought many of our families here, has appeared to be benevolent but has forced our parents to silence themselves for our survival, which has, in turn, led to silence on racism in our communities. Our parents, ourselves, and those around us have all been exposed to anti-imperial thought, but we choose to never speak about it. In that political silence, which becomes political forgetting, we need to firstly un/re/learn what imperial mechanisms brought us here and how they necessarily have been anti-Black and anti-Indigenous. Then we need to educate our communities.

Thomas Elias Siddall 劉夢飛 is an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto and does research on global youth movements as movements of re-spacialization. They are interested in Queer politics and how the politics of space shape our narratives of home.

References

Asselin, Pierre. “The Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the 1954 Geneva Conference: A revisionist critique”. Cold War History 11, no. 2 (2011): 155-195.

Blair, Eric Arthur. “How a Nation is Exploited – The British Empire in Burma”. Le Progrès Civique, CW 86, (1929).

Boustan, Leah Platt. “Was Postwar Suburbanization “White Flight”? Evidence from the Black Migration”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125, no. 1 (2010): 417-443.

Choe, Sang-hun. “‘Tell Me Who My Mother Is’: A Korean Adoptee Seeks Her Roots”. The New York Times (2020). Accessed: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/02/world/asia/south-korea-adoptions.html

Chow, Kat. “’Model Minority’ Myth Again Used As A Racial Wedge Between Asians And Blacks”. NPR (2017). Accessed: https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/04/19/524571669/model-minority-myth-again-used-as-a-racial-wedge-between-asians-and-blacks.

Goetz, Edward, Rashad A. Williams, and Anthony Damiano. “Whiteness and Urban Planning”. Journal of the American Planning Association 86, no. 2 (2020): 142-156.

Gupta, Arpana, Dawn Szymanski, and Frederick T. L. Leong. “The “Model Minority Myth”: Internalized Racialism of Positive Stereotypes as Correlates of Psychological Distress, and Attitudes Toward Help-Seeking”. Asian American Journal of Psychology 2, no. 2 (2011): 101-114.

hooks, bell. “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance”. In black looks: race and representation, (New York: Routledge, 1992): 366-380.

Johnston, Ron, Michael Poulsen, and James Forrest. “The Geography of Ethnic Residential Segregation: A Comparative Study of Five Countries”. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 97, no. 4 (2007): 713-738.

Kao, Mary Uyematsu. “Salute to Yuri Kochiyama (May 19, 1921 – June 1, 2014)”. Amerasia 40, no. 2 (2014): 112-114.

Kim, Jodi. “The Ending Is Not an Ending At All”: On the Militarized and Gendered Diasporas of Korean Transnational Adoption and the Korean War. positions: asia critique 23, no. 4 (2015): 807-835.

Lowe, Lisa. “The Intimacies of Four Continents”. In The Intimacies of Four Continents, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015): 1-42.

Ma, Kyunghee. “Korean Intercountry Adoption History: Culture, Practice, and Implications”. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 98, no. 3 (2017): 243-251.

Morey, Glenn, and Julie Morey. “Given Away: Korean Adoptees Share Their Stories”. The New York Times (2019). Accessed: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/23/opinion/korean-adoptees.html.

Munasinghe, Viranjini. Callaloo or Tossed Salad?: East Indians and the Cultural Politics of Identity in Trinidad. (Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press, 2001).

Murray, Paul T. “Blacks and the Draft: A History of Institutional Racism”. Journal of Black Studies 2, no. 1 (1971): 57-76.

Petersen, William. “Success story, Japanese American style”. The New York Times (1966). Access: http://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/US_History_reader/Chapter14/modelminority.pdf.

Piper, Dannielle. “What Happened to Vancouver’s Black Neighbourhoods?” The Tyee (2019).

Renzulli, Linda, and Lorraine Evans. “School Choice, Charter Schools, and White Flight”. Social Problems 52, no. 3 (2005): 398-418.

Wang, Tao. “Neutralizing Indochina: The 1954 Geneva Conference and China’s Efforts to Isolate the United States”. Journal of Cold War Studies 19, no. 2 (2017): 3-42.

Waters, Johanna. “Flexible Citizens? Transnationalism and citizenship amongst economic migrants in Vancouver”. Canadian Geographer 47, no. 3 (2003): 219-234.

[1] Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents. In The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 7.

[2] Dannielle Piper, What Happened to Vancouver’s Black Neighbourhoods? The Tyee, (2019).

[3] Lowe, “Intimacies,” 18.

[4] Ibid., 23.

[5] Viranjini Munasinghe, Callaloo or Tossed Salad?: East Indians and the Cultural Politics of Identity in Trinidad (Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press, 2001), 143.

[6] Pierre Asselin, “The Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the 1954 Geneva Conference: A revisionist critique”, Cold War History 11, no. 2 (2015), 157.

[7] Tao Wang, “Neutralizing Indochina: The 1954 Geneva Conference and China’s Efforts to Isolate the United States”, Journal of Cold War Studies 19, no. 2 (2017), 9.

[8] Glenn Morey and Julie Morey, “Given Away: Korean Adoptees Share Their Stories”. The New York Times: 7:25. (2019). AND Jodi Kim, ““The Ending Is Not an Ending At All”: On the Militarized and Gendered Diasporas of Korean Transnational Adoption and the Korean War”, positions: asia critique 23, no. 4 (2015), 824.

[9] Morey and Morey, “Given Away…”, 2:35.

[10] Ron Johnston, Michael Poulsen, and James Forrest, “The Geography of Ethnic Residential Segregation: A Comparative Study of Five Countries”. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 97, no. 4 (2007), 715.

[11] Leah Platt Boustan, “Was Postwar Suburbanization “White Flight”? Evidence from the Black Migration”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125, no.1 (2010), 419. AND Linda Renzulli and Lorraine Evans, “School Choice, Charter Schools, and White Flight”. Social Problems 52, no. 3 (2005), 400.

[12] Mary Uyematsu Kao, “Salute to Yuri Kochiyama (May 19, 1921 – June 1, 2014)”. Amerasia 40, no. 2 (2014), 114.

[13] Arpana Gupta, Dawn Szymanski and Frederick T. L. Leong, “The “Model Minority Myth”: Internalized Racialism of Positive Stereotypes as Correlates of Psychological Distress, and Attitudes Toward Help-Seeking”. Asian American Journal of Psychology 2, no. 2 (2011), 102. AND William Petersen, “Success story, Japanese American style”. The New York Times (1966).

[14] Paul T. Murray, “Blacks and the Draft: A History of Institutional Racism”. Journal of Black Studies 2, no. 1 (1971), 69.

[15] Johanna Waters, “Flexible Citizens? Transnationalism and citizenship amongst economic migrants in Vancouver”. Canadian Geographer 47, no. 3 (2003), 223.

[16] bell hooks, “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance”. In black looks: race and representation, (New York: Routledge. 1992), 369.

[17] Edward Goetz, Rashad A. Williams, and Anthony Damiano, “Whiteness and Urban Planning”. Journal of the American Planning Association 86, no. 2 (2020), 145.

[18] Eric Arthur Blair, “How a Nation is Exploited – The British Empire in Burma”. Le Progrès Civique, CW 86 (1929).